First in a series

At a recent news conference, Celtics NBA star Jaylen Brown said, “I want to launch a project to bring Black Wall Street here in Boston,” according to CNN and ESPN. What would it take?

Venture capitalists say they don’t care about Black or white, just green. One thing Wall Street does is make ownership of companies public. But first, we need more Black and brown founders.

Let’s examine the Black tech founder world.

The Boston metro area rivals Silicon Valley in terms of innovation. In 2015, the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy metro area ranked third out of 130 such regions in both the number of venture capital deals and the number of companies receiving that kind of funding.

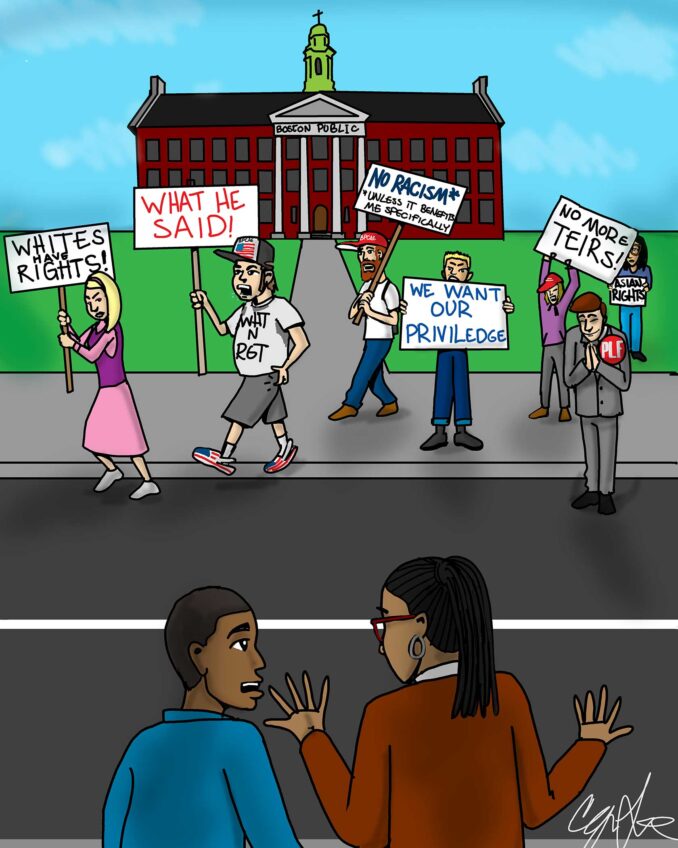

Boston also has a sizable Black population, both in terms of its absolute and relative size. So, why then does Boston have so few tech companies with Black founders? And why do some smaller metros have more Black tech founders than Boston when they don’t have the same competitive advantages?

Based on my research, the number and success of Black tech founders are largely immaterial to the success of the local economy in eastern Massachusetts. The result is a lackluster effort to increase the number of Black tech founders or accelerate their success.

According to CrunchBase, Black founders in the country received less than 2% of venture funding annually between 2015 and summer 2020, while 13% of Americans identify as Black or African American. In an efficient market, capital should flow to the opportunities with the best risk-adjusted levels of return. The fact this doesn’t happen means there is some type of failure or friction in the marketplace. James Norman spells out the barriers in his article, “A VC’s Guide to Investing in Black Founders,” as does “The Black New Venture Competition,” a Harvard Business School case study written by Karen Mills, Jeffrey J. Bussgang, Martin Sinozich and Gabriella Elanbeck.

Why should we care? For one, we can make the world a better place. The planet faces many challenges. We need as many people as possible working on solutions — both to improve our surroundings and to provide better returns for socially conscious investors. Michael Porter’s theory of shared value depends upon the free flow of capital to people and opportunities. The fact this doesn’t happen is a problem to be solved.

We can also solve so-called “niche” problems by helping Black and brown founders. There are problems millions of individuals of different ethnicities and genders face. Such issues often go unnoticed by mainstream investors because they are simply unaware of these felt needs.

Niche is understood differently when applied to ethnic groups. Rubix Life Sciences, an area Black-founded tech company that uses data analytics for underrepresented populations within health research, was considered to have a niche focus, even though there are several billion people in the world that fall into that niche. Solutions of this kind provide the potential for significant returns.

Tech creates good jobs. With equity, it’s a great wealth generator. Tech can create millionaires, transform a community and help address gentrification and other issues.

Then there is the national competitiveness factor. We will become more competitive as a nation when we include more people in the tech revolution. The digital divide is not technology haves and have-nots, as everyone from all income levels and social groups have a smartphone. The digital divide is those who consume technology and those who produce technology.

And let’s not forget about role models. We need examples to inspire and create the next generation of problem-solvers, wealthcreators and philanthropists. Those in control of venture capital need to see examples of Black entrepreneurs as successful founders in order to feel comfortable taking the meetings and making the investment.

Finally, there’s proof that these investments spur returns. Reinventure Capital, a venture fund focused on “investing in a more perfect multicultural, equitable, and prosperous union,” shows that BIPOC funds can outperform their peers.

Ed Gaskin is executive director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets in Boston.