The city of Boston is approaching a 50-year milestone. We are about to observe the anniversary of school desegregation. The crisis starting in 1974 has always been a stain on the fabric of our community. The seeds of that crisis sprouted in the 1960s, when many organizations were culpable in creating this problem.

The Massachusetts Education Commission released a report in 1965 stating that more than half of the Black students in Boston schools were attending institutions that were 80% Black, it said, because of housing segregation. Just like the South, Boston had a history of segregated schools, and much of the reason lay at the feet of the Boston Housing Authority. It acted as a buffer against integration by setting aside units in South Boston as a whites-only enclave, especially for those people who did not want to move to the nearby Columbia Point projects. There was also a system of redlining, and steering of Black residents to areas of Boston where it would be difficult to obtain federally backed loans. These “red” areas of the city were considered unfit to receive loan funding.

That same year, the NAACP filed a lawsuit against the city of Boston to desegregate the school system. The outcome was the state Racial Imbalance Act of 1965 that ruled that segregation in Massachusetts public schools was illegal. Activists Ruth Batson and Mel King were among many who protested and took the fight to the Boston School Committee, whose elected members refused to believe there was segregation in the city’s schools, despite factual evidence to the contrary. School Committee member Joseph Lee and President Louise Day Hicks continually thwarted any actions to desegregate the schools. But both did advocate busing students in white communities to overcome overcrowding in some areas.

After continued resistance, the School Committee was sued for violating the 13th and 14th amendments and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The lawsuit, Morgan v. Hennigan, included a plethora of painful accusations, from neglect of certain schools to discrimination in hiring, student classifications and admissions to certain schools and lower expenditures on students of color. The suit was brought by 44 students and 14 parents of Black students, including lead plaintiff Tallulah Morgan, a Black mother of three school-aged children. A trial was held in 1973.

Finally, U.S. District Judge W. Arthur Garrity ruled in June 1974 that the School Committee had “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers, and school facilities.” Garrity’s ruling was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court.

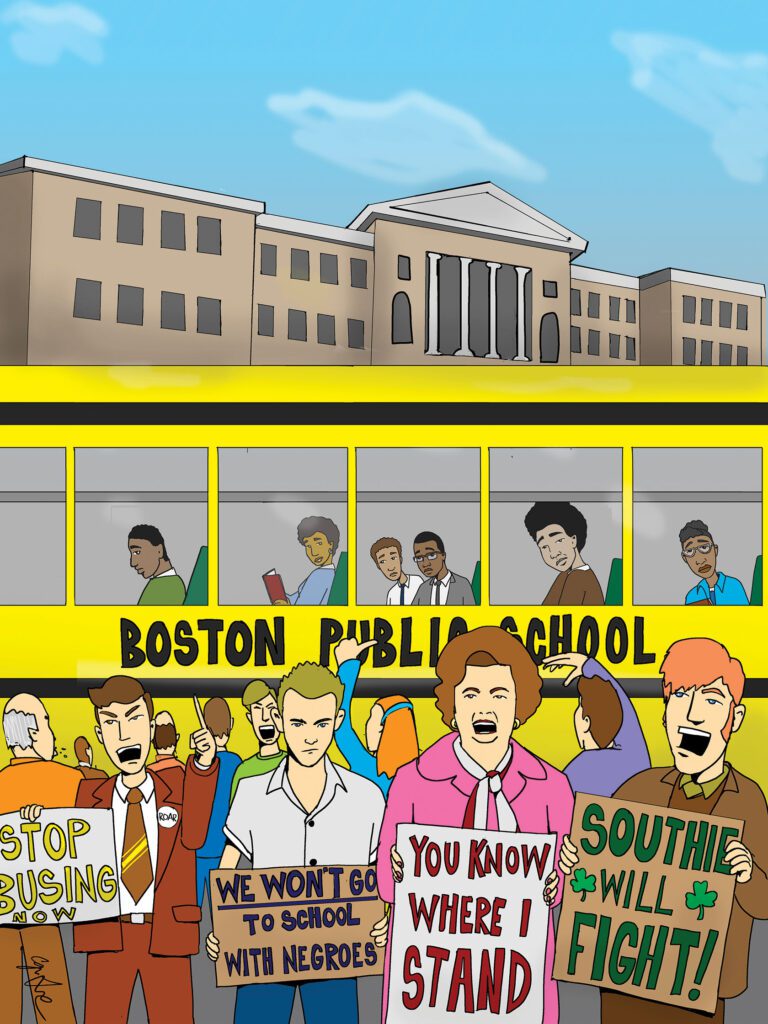

The violent reaction to the court-ordered remedy led to one of the most tumultuous and difficult times in the city’s history. Violence reverberated across Boston as Black students were bused to formerly white schools, where they took the brunt of the punishment and anger. Bricks and rocks were hurled at buses. Many Black residents wisely refused to visit certain parts of the city.

Many white parents started enrolling their students in parochial or private schools, or leaving the city for the suburbs to avoid their children being bused to formerly Black public schools. The city’s school enrollment dropped 25%. A relatively small number of Black and Latino students chose to enroll in METCO, a program that voluntarily integrated white suburban campuses. METCO’s intent was to provide Black and brown students additional options and increase cultural diversity in suburban schools.

Throughout all of this uproar, one thing remained constant: Equal education for students of color was absent — a fact Black parents through their perseverance revealed to the country. Something had to be done to create a better learning environment.

School desegregation is just 50 years old, and there is always resistance to change. Today the school-age demographics have changed. 87% of the school-age children are of color, almost half of them Latino. The number of charter and specialized schools is growing in the city, catering to an increasingly diverse minority population. Unfortunately, there is still a disconnect within the city’s educational system between the haves and the have-nots. The current focus on the apparent racial imbalance in Boston public school staffing illustrates another challenge and the ongoing quest for equality in education.

Busing to desegregate 1970s Boston failed to bring about the changes the city needed, but using this meme of defeat helps deflect blame that the educational system is still not working for many people in communities of color. It also gives aid to those who believe that segregation by class and color is inevitable, even in 2023. That thinking must change so that it does not take another 50 years to achieve equality in education for Black and brown children.