‘American Watercolors, 1880–1990: Into the Light’ at Harvard Art Museums

“American Watercolors, 1880–1990: Into the Light,” the beguiling exhibition on view at the Harvard Art Museums through Aug. 13, rewards multiple visits. Adding to the joy, admission to the museum, at 32 Quincy Street off Harvard Square, is now free to all.

Presenting 100 watercolors spanning more than a century, the exhibition and its gorgeous catalog invite visitors to savor works by about 50 A-list artists drawn to the tactile, hands-on immediacy of the medium. Horace D. Ballard, a curator, writes that while accessible to all — from children to adults — for artists, it can be “a medium for the expression and training of one’s humility.”

Bill Traylor, “Mule and Plow” c. 1939–42. Opaque watercolor and graphite on paperboard. Collection of Didi & David Barrett © Bill Traylor Family Trust. IMAGE: COURTESY OF THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS

Riveting works by canonical Black artists include “Mule and Plow” by Bill Traylor (c. 1853–1949), which shows jaunty figures, silhouetted in black, of a man guiding a mule-drawn plow across a field. It was a scene the artist knew well. Born into slavery in Alabama, Traylor was later a sharecropper and then, in his 80s, living on the streets of Montgomery, a self-taught artist. Foraging scraps of paper, he produced nearly 1,500 images over three years. Long after his death, his works were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1995 and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2018–19.

In a video, Margaret Morgan Grasselli, an exhibition curator and catalog editor, singles out Traylor’s image, which he made on the back of a tobacco poster. “This is a wondrous composition … one of the most elegant and captivating in the show.”

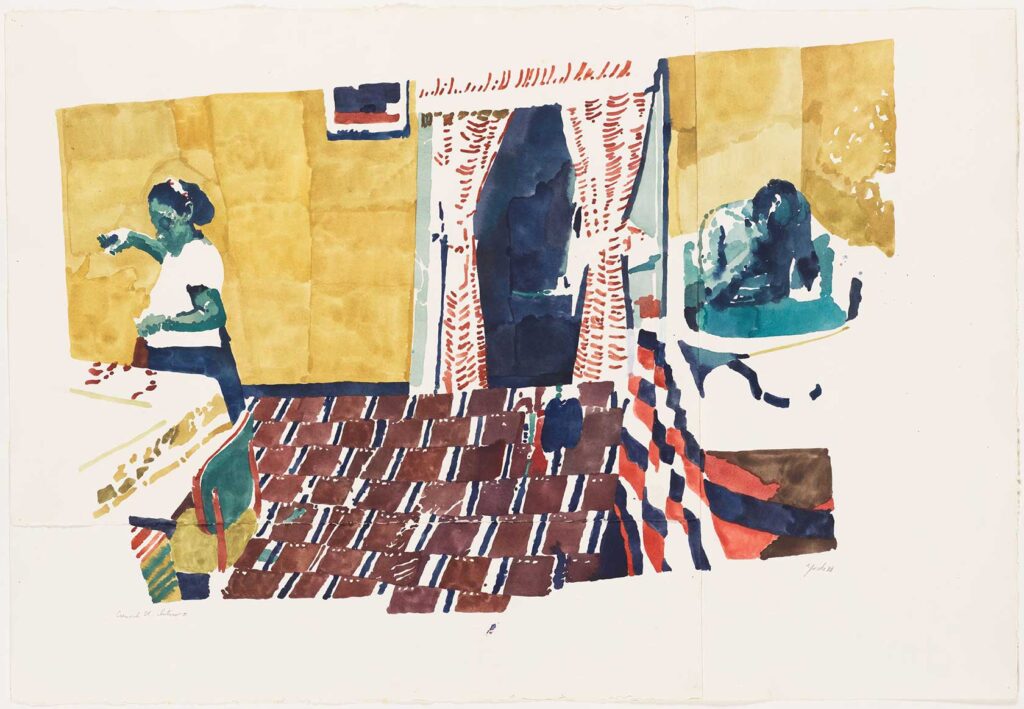

Rivaling a nearby 16-foot Sol Lewitt mural with swirling waves of color is an image of a Roxbury childhood by Richard Foster Yarde (1939-2011), a leading watercolor artist of the late 20th century. “Cunard Street, Interior II” (1980) renders two figures: a woman busy at a table and, in the bathroom, a man in a tub. Juxtaposed on different sheets of paper, with parts uncovered by paint, they are separated by tile-like geometric patterns in bold colors.

An untitled work by Sam Gilliam (1933–2022), who in 1972 became the first Black artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, demonstrates his practice of crumpling and then flattening paper stained with watercolor and ink. The resulting abstraction evokes a coral reef viewed from above.

Beauford Delaney, “Untitled” 1964. Watercolor on white wove paper mounted to canvas mounted to a stretcher. © Estate of Beauford Delaney

IMAGE: COURTESY OF THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS

Two watercolors by Romare Bearden (1911-1988) demonstrate his delicate touch: In one, the central figure nuzzles a white bird, while tender light falls on the limbs of the women surrounding her. In the other, a miniature island scene glimmers with jeweled tones. Bearden studied art at the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill after serving in World War II in the all-Black 372nd Infantry Division. While holding a job for three decades as a social worker, he forged a distinguished career as an artist, and received the President’s National Medal of Arts in 1987.

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979) is represented by an untitled 1964 work acquired for the museum by Joachim Homann, the exhibition’s curator and catalog editor. Speaking by phone, Homann notes how the radiance of Delaney’s layered transparent glazes reaches beyond the frame, and he quotes what James Baldwin wrote about his friend that year: “I learned about light from Beauford Delaney, the light contained in every thing, in every surface, in every face … and this light held the power to illuminate, even to redeem and reconcile and heal.”