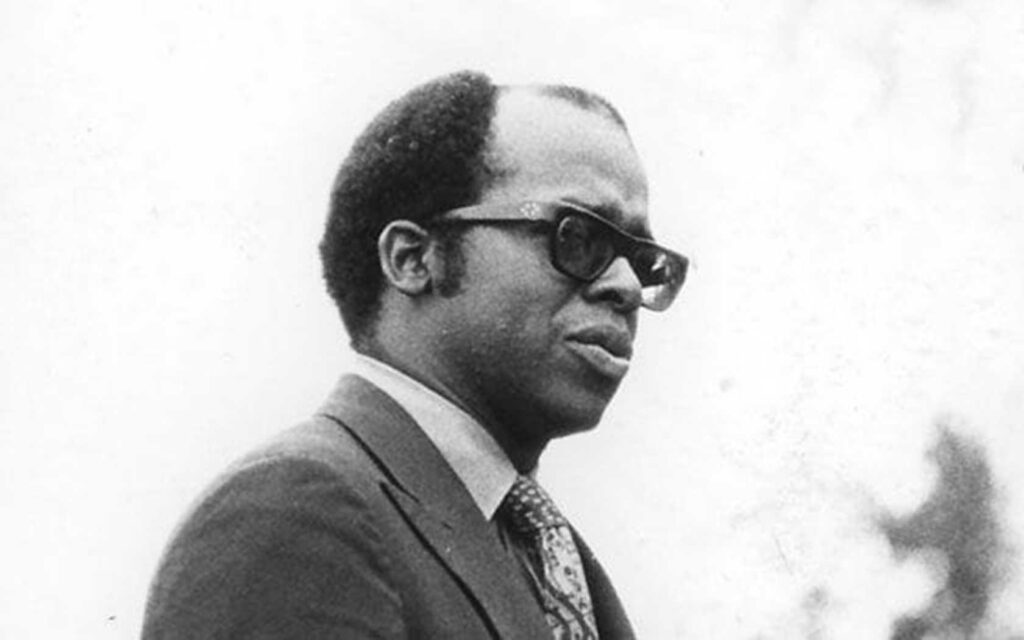

Fifteen years ago this month, renowned civil rights attorney Thomas Irving Atkins — known citywide as Tom Atkins — lost a 15-year battle to Lou Gehrig’s Disease. He had spent his entire life relentlessly fighting for racial equality and against racial discrimination, expanding his crusade beyond Boston as special counsel and general counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its New York national office.

Fifteen years ago this month, renowned civil rights attorney Thomas Irving Atkins — known citywide as Tom Atkins — lost a 15-year battle to Lou Gehrig’s Disease. He had spent his entire life relentlessly fighting for racial equality and against racial discrimination, expanding his crusade beyond Boston as special counsel and general counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its New York national office.

Atkins was born in Elkhart, Indiana, on March 2, 1939. He was the youngest of five children of Lillie Mae (Curry) Atkins, a domestic, and Norse Pierce Atkins, a Pentecostal minister who also held jobs as a railroad worker and sanitation worker.

At age 5, young Thomas was stricken with polio. Although it was thought he’d never walk again, hell-bent on walking, he successfully completed a three-year rehabilitation program.

Atkins attended Elkhart High School, where he was elected the first Black student body president. Upon graduation, he attended Indiana University where his classmates elected him the school’s first Black sophomore class president and the first Black student body president of a Big Ten school. Additionally, Atkins was president of the Indiana University Residence Hall Association. He received a bachelor’s degree in political science with Phi Beta Kappa honors in 1961.

A year later, Atkins acquired a master’s degree from Harvard University, majoring in Far East Studies. He was working toward obtaining a doctorate when he left the university to become more engaged in Boston’s civil rights movement.

Atkins served as executive secretary of the Boston Branch of the NAACP from 1963 to 1965. It was one of the most active two-year periods in local NAACP history as he was active in a multitude of local issues, most notably de facto segregation in Boston’s public schools and housing.

Near the end of 1965, Atkins resigned as executive secretary to assume the position of general manager of Bill Russell Enterprises and Slade’s Restaurant, at the time owned by Celtics coach and basketball legend Bill Russell.

In November 1967, Atkins made a successful bid for a citywide seat on the Boston City Council. Shortly after his election, he told the citizens of Boston, “For the past nine months, I campaigned in every part of our city. During that time, it became apparent that there were many thousands of people who were willing to join with us in working and fighting for a Boston in which we would all benefit. This was the thesis of my entire election strategy, and I feel that the voters who gave me seventh place, out of the 18 candidates, confirmed the validity of that thesis. I intend to keep faith with those voters by proceeding immediately to work on the problems which were of concern to them, and which challenge our city.”

He served two two-year terms, during which he provided exceptional leadership implementing the city’s antipoverty, model cities and urban renewal initiatives.

After acquiring his law degree in 1969 from Harvard, Atkins also taught urban politics at Wellesley College.

Atkins’ successful 1969 re-election campaign for City Council convinced him to run for mayor of Boston in 1971 as the first African American candidate. In a crowded field comprising Kevin White, Joseph Timilty and Congresswoman Louise Day Hicks, he amassed 12 percent of the vote, which he called a “credible” showing, given the racial polarization of the city then.

But Atkins is most remembered locally for his leading role in desegregating the Boston Public Schools in the 1970s. Thirteen schools in Boston were at least 90 percent Black at the time. More importantly, the budgets provided for these schools were lower by $125 per pupil than the average budget for a white school in Boston. Atkins served as associate trial counsel in the class action school desegregation case of Morgan v. Hennigan. In a 1974 landmark court ruling, U.S. District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered the Boston Public Schools to bus students citywide to achieve racial integration.

Reflecting on that period in an interview with the Boston Herald, Atkins recalled desegregating the public schools as a turning point.

“It was an event of such significance and power. It transformed the politics of the Black community,” he said. “It created a cadre of people who know how to get things done.”

Ted Landsmark, who worked with Atkins in the late ’70s as a lawyer at his Boston law firm, Atkins and Brown, told the Boston Globe in 2008, “He was clearly the most brilliant and insightful civil rights lawyer, both in and beyond Boston, to take on the challenges of school desegregation.”

In a 1994 interview with the Globe, Atkins quite bluntly said court-ordered busing “forced open the lid on Boston’s poorly kept, nasty little secret, which was citywide racism … Members of the [Boston] School Committee placed their own political salvation over the welfare of the city, the school system and the schoolchildren.”

From 1971 through 1975, Atkins served as Secretary of Communities and Development in Massachusetts Governor Francis W. Sargent’s cabinet. He served as special counsel to the NAACP national office from the mid-1970s, handling school desegregation cases and working closely with NAACP’s then-general counsel, Nathaniel R. Jones.

From 1980 through 1984, Atkins served as general counsel to the NAACP. As its top attorney, he supervised all litigation involving the national office in the areas of school desegregation, voting rights, employment discrimination and police misconduct. With respect to fair housing, he litigated housing discrimination class action cases in the federal courts concerning Boston, New York City and Yonkers, New York.

In 1982, Indiana University awarded Atkins the College of Arts and Sciences Alumni Award, and in 1995, it awarded him the Distinguished Alumni Service Award.

Atkins died at 69 in Brooklyn, New York, on June 27, 2008.

In 2011, thanks to a unanimously passed order introduced by then-Boston City Councilor Felix G. Arroyo and then-Council President Stephen Murphy, Atkins was officially recognized with a new conference room in his name on the fifth floor of City Hall. Arroyo described him as “a man of courage, a civil rights trailblazer and a champion of socioeconomic justice.”