Last week’s Supreme Court ruling on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act stunned many people in Black and brown communities. Many had anticipated the worst, expecting the conservative majority to vote 6-3 to sustain the new voting districts designed by Alabama’s Republican-led legislature. Brett Kavanaugh and John Roberts, however, sided with the liberal members of the court and overturned the plan in a 5-4 ruling. The vote upheld a lower court ruling pointing out that African Americans were severely underrepresented in Alabama’s seven congressional districts, even though they constitute about a quarter of the population. Unanimously, a three-judge panel had ordered the state to create a second congressional district with a Black majority. The state appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court.

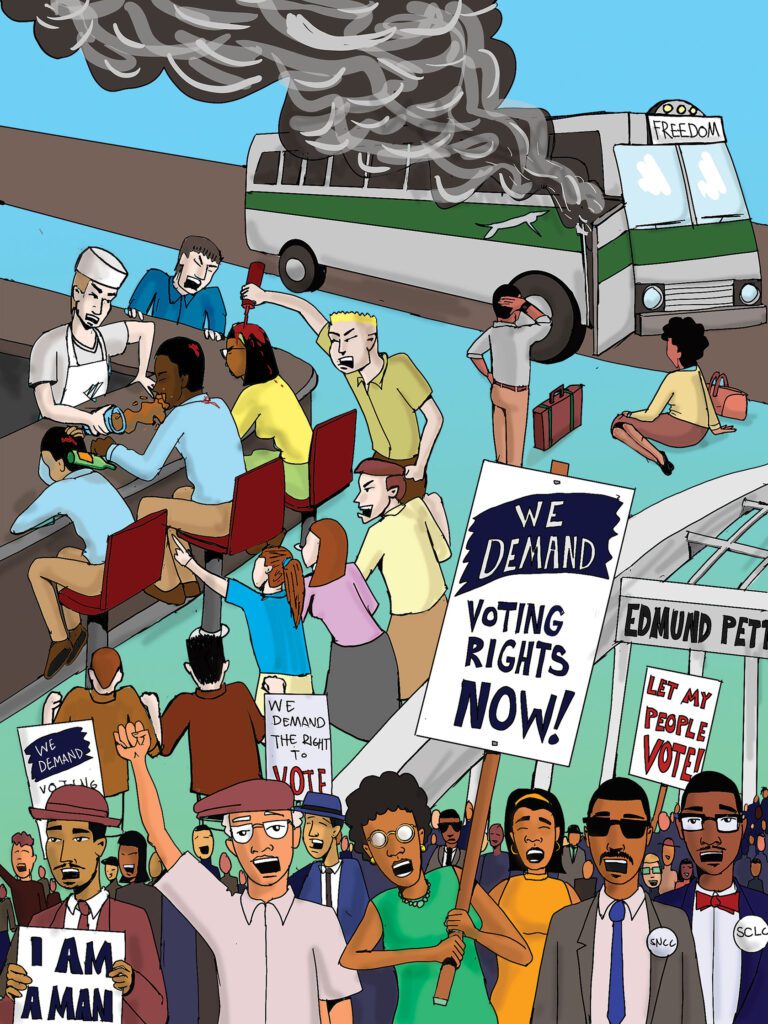

The case, Allen v. Milligan, harkens back to the reasons the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. After slavery ended, all southern states used nefarious means to maintain white supremacy, blocking Black and brown people from voting with poll taxes, property ownership requirements, literacy tests and acts of extreme intimidation.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a monumental series of events set the table for President Lyndon Johnson to sign this law on August 6, 1965. Brown v. Board of Education, five combined lawsuits, in 1954 outlawed school segregation. In 1955, the year-long Montgomery bus boycott protested segregation in seating on city buses, spurred by the arrest of Rosa Parks for not giving up her seat to a white passenger.

Two years later, the Little Rock Nine attempted to integrate a high school in the Arkansas city but were initially blocked. President Dwight Eisenhower signed the first Civil Rights Act in 1957, empowering the Justice Department to obtain injunctions against any organizations that interfere with the right to vote. That law also established the U.S. Civil Rights Commission to investigate discriminatory practices and recommend the prosecution of violators of

the law.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy sent National Guard troops to help integrate the University of Alabama over the objections of Governor George Wallace. That same year, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom drew 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial, where the Rev. Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” speech. Five months prior to Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act, 600 civil rights marchers walked from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to protest voter suppression after, in front of the television-viewing nation, they were brutally attacked by police. The new law eliminated the arbitrary use of literacy tests and other discriminatory means of suppressing the Black vote. As a result, voting increased in many of the southern states, even though local enforcement of the act was ignored.

By 2013, the Supreme Court’s conservative wing had deemed some of the provisions of the Voting Rights Act obsolete, specifically stating that the federal government’s special oversight of election procedures in certain states was no longer needed. This rule change resulted in many states once again adopting voter suppression practices.

The state of Alabama became the center for a crackdown on the people’s right to vote in 2020. Republican legislators said that the redrawn districts were race-neutral and not biased in any way. The plaintiffs in Allen v. Milligan showed that the state’s racial makeup after the 2020 Census had changed, with the Black population having grown by 3.8% and the white population having shrunk by 4%. The plaintiffs claimed that there was indeed a need for another minority-majority district and sued, winning a U.S. District Court declaration that the Alabama legislature violated the Voting Rights Act. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has pointed out that the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted specifically to protect all people’s, including former slaves,’ ability to vote, and that the law was not intended to be “race-neutral or race-blind.”

This recent Supreme Court ruling has far-reaching consequences for the makeup of Congress. In addition to Alabama, Louisiana is in a redistricting fight for similar reasons. A burgeoning Black population makes up 30% of the Bayou State, which has only one minority-majority district out of six.

The long struggle to maintain voting rights for African Americans has been well documented and continues to confuse and frustrate the most ardent followers of the civil rights movement. But people like Evan Milligan, a native Alabamian and lead plaintiff in the case, continue to fight for expanded access to democracy for every citizen. Milligan told Reuters, “Why are we choosing this moment to step back from our traditions that have expanded access to the ballot?” He is right. We should never step back. Never.