Hackathons usually involve computer programmers and sometimes engineers gathering together to brainstorm, trying to solve a technical challenge. But the 75 activists, faith leaders and students assembled for a hackathon at MIT last weekend were focused on an economic and social challenge: the racial wealth gap.

“As far as I’m concerned, there’s no bigger challenge than the racial wealth gap,” explained Karilyn Crockett, a professor of urban history, public policy and planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who organized the novel hackathon.

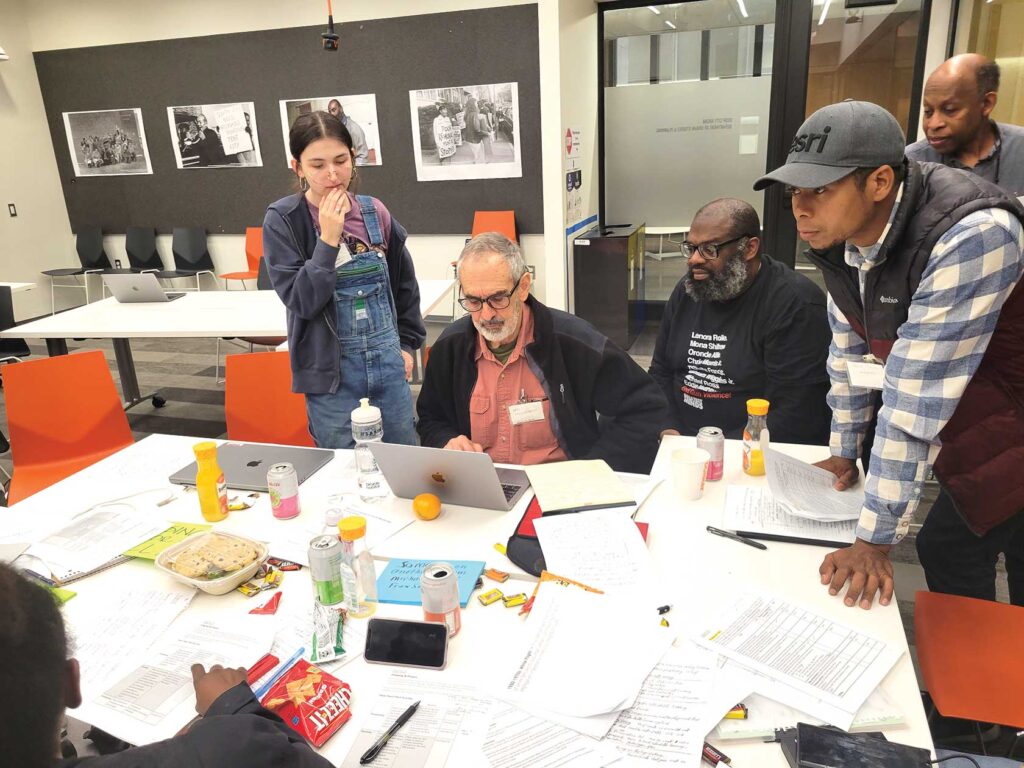

Teams of collaborators spent a spring Saturday gathered around small tables inside a cavernous MIT building that fronts on Massachusetts Avenue, trying to extract from historical archives potential solutions to the massive wealth gap between white and Black residents of Boston.

The second “Hacking the Archive” session on May 20, which followed another in 2019, narrowed the focus to housing as a prime generator of wealth at a time affordable homes are hard to find locally.

One of three winning teams proposed a radical solution: abandoning traditional homeownership for more feasible options that can still build wealth.

“We felt that the barriers to homeownership are the stock. We don’t have stock in the city of Boston,” Connie Forbes said during the team’s five-minute pitch, referring to the supply of existing homes and their high cost.

“Why not look at alternatives that not only provide a stable housing situation, but also equity? So co-ops — and there are several in the community that I am from that were built by churches,” said Forbes, a Roxbury resident.

Residents of co-ops, or housing cooperatives, buy shares in the company that owns the building and pay maintenance fees in exchange for the right to occupy a unit. A co-op’s rules may allow shareholders to sell their shares at market rates or limit the price that residents can get when they move out.

Forbes pointed to Marksdale Gardens, built by St. Mark’s Congregational Church and converted to a co-op in 1984, and St. Joseph’s Community, named after a now-closed Catholic church. Both of these Roxbury co-ops were built in the 1960s and limit the equity that residents can earn when they sell.

“You don’t have a mortgage that locks you in for 30 years,” she said in an interview. “It’s a combination of homeownership and rental at its best.”

Forbes said she lives in a house that has been in her family for three generations. “We couldn’t live where we are now if we had to come in this year, or even the last 10 years,” she said.

Another team member, Breana Norris, lives in Somerville as she attends the Harvard Divinity School and works for Greater Boston Legal Services. Norris said she could wind up inheriting her parents’ home in Los Angeles or her grandparents’ home.

“They’ve already created their intergenerational wealth,” Forbes said of Norris’ family.

Other alternatives to homeownership that the team endorsed were community land trusts like that of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, lease-to-own arrangements and “shared-equity deed-restricted homes,” which can be resold after 30 or more years for a set price, limiting appreciation and thus keeping them affordable for the next generation of buyers.

Asked whether the team was calling for abandoning the American dream of homeownership, Forbes replied, “The dream has to come into the 21st century, at least in the urban areas.”

Other teams suggested ways that suburban churches, in particular those affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry in Roxbury, could help increase Black wealth.

Those recommendations include suburban churches spending more money with businesses owned by people of color, reassessing how their endowments are invested, advocating for additional affordable housing “in their own suburbs” and raising funds to support low- or no-interest loans to buy homes in Roxbury.

One Black church in Dorchester is moving to add to the supply of affordable housing. Pleasant Hill Baptist Church plans to partner with Nuestra Comunidad Development Corporation to build 29 units beside and behind the church on Humboldt Avenue, according to Rev. Miniard Culpepper, the church’s pastor. Community meetings and zoning hearings are expected to occur this summer.

The Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry, Greater Boston Interfaith Organization and Morning Star Baptist Church were among the community partners participating in the interracial, intergenerational hackathon.

Two more are planned in coming years, organized by Crockett and funded by a grant from the endowment of Trinity Church Wall Street in New York City.

Separately, Crockett is partnering with the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston to update the 2015 “Color of Wealth” report that showed a yawning disparity between the assets of the city’s white and Black residents. She has indicated it will take three years to complete the new report, which will be expanded to examine the situation in the Boston metropolitan area and Gateway Cities around the state, using a larger sample of residents.

That report, Crockett said, will explore the root causes of the racial wealth gap and model strategies for closing it.