CORI reform advocates call for changes in state law

Requesting changes to probation records term

Advocates for access to sealing and expunging criminal records are citing progress but also continuing hurdles in the ability of Massachusetts residents to take advantage of changes in how long and under what conditions a prior offense can stay on someone’s public record.

State laws around sealing of records have been overhauled twice since 2010, when the minimum wait time for sealing them was lowered from 15 years to 10 for felonies and from 10 to five years for misdemeanors. As part of broad criminal justice reform measures passed in 2018, those wait times were lowered again, from 10 to seven years for felonies and from five to three years for misdemeanors.

Those changes mean more state residents are eligible sooner to apply to have their records sealed or expunged. Expungement usually applies to charges incurred as a juvenile.

Last year, the state received about 5,700 petitions for sealing and sealed nearly 60,000 individual charges, according to Nina Pomponio, general counsel for the Massachusetts Probation Service. The agency also received roughly 1,200 expungement petitions, about 250 of which were eventually granted by court officials.

On a recent tour of the Massachusetts Probation Service, State Rep. Chynah Tyler had plaudits for the office, commending what she describes as a good-faith effort to accommodate the surge in demand for those services.

“If you call, if you reach out today, you pretty much get a one-on-one customer service, and they literally will call you personally and walk you through it if you’re confused,” Tyler told the Banner.

But the process could still reach more residents sooner, Tyler said, noting her support for yet another reform that could change the landscape of criminal records in Massachusetts: automatic sealing of such records when they hit their sunset.

Tyler has sponsored one of several bills currently pending in the legislature that would instruct the state’s Office of Probation to automatically seal records for those eligible –without their having to apply for the service.

Tyler, who represents the 7th Suffolk District, which encompasses much of Roxbury, says studies have shown her district includes “one of the most incarcerated corridors in the Commonwealth,” with high concentrations of incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated residents along Blue Hill Avenue.

“You’d be surprised at the number of people who have a CORI,” said Tyler, referring to the Massachusetts Criminal Offender Record Information Act.

Those records, Tyler noted, can haunt residents transitioning from incarceration, or simply trying to move on with life after contact with the state’s legal system. CORI records can include charges for which there was never a conviction, including cases in which the state dropped charges or declined to prosecute.

“It is sometimes impossible, or very difficult to get people reconnected” with jobs and other supports “because of the status of their CORI,” Tyler said, even though “You’ve already served your time — so making someone suffer again is kind of making someone serve time twice.”

Sealing records via the state’s Office of Probation is one way for those residents to gain better footing.

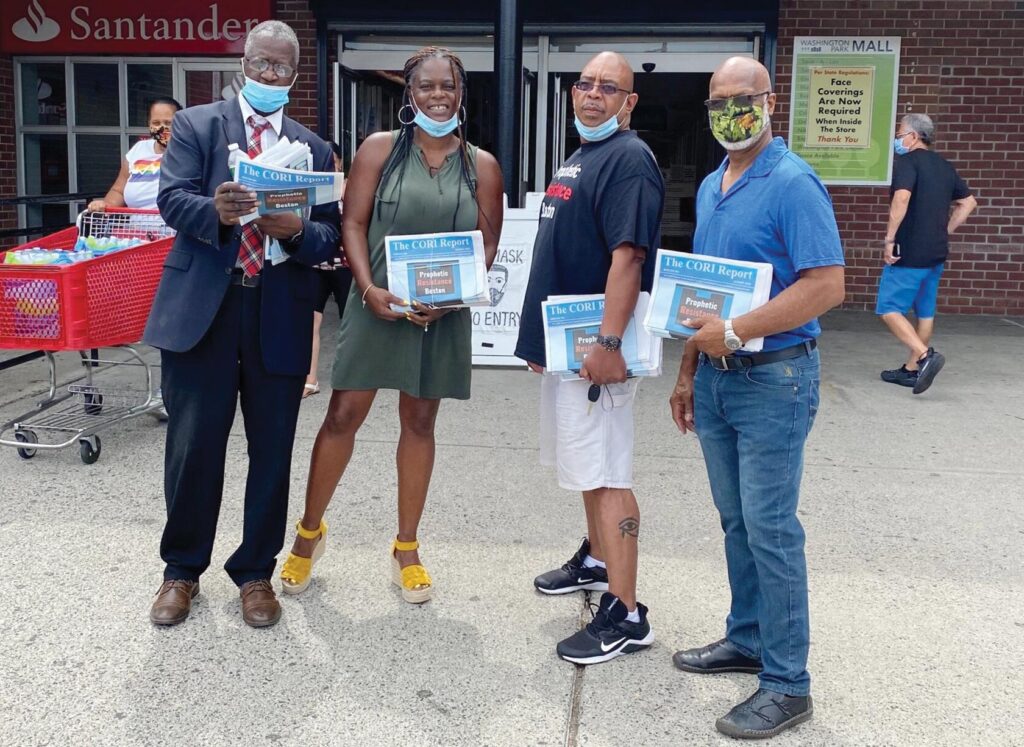

But there remain various barriers to eligible residents, said Danielle Williams of Prophetic Resistance, a faith-based organization that has been running free sealing and expungement clinics around Boston.

For one thing, notes Williams, many residents simply don’t know where to begin – and are at risk for being exploited.

“We’ve had many folks that have come to get their CORI sealed and they’ve said that lawyers are charging them $700 and up,” Williams said. “We provide a free service.”

For another, the process can be lengthy. Successful applications to seal records can take of the outcome, Williams said.

Those wait times can have an enormous negative impact on those seeking jobs and housing, said Aderonke Lipede, a volunteer attorney with Prophetic Resistance as well as a minister at Charles Street AME Church.

“Because you have people who are in the process of looking for jobs, and sometimes their record becomes a problem during the interviewing process, and sometimes you’ll have an employer saying ‘sorry, we can’t go forward with you,’” Lipede said. “It’s an impediment to moving forward after you’ve served your time or you’ve done your probationary period, it’s sort of a chain around one’s neck if they’re not able to seal it.”

At the same time, Pauline Quirion of Greater Boston Legal Services said the bureaucratic process itself can be major barrier to many residents.

“It’s a complicated system, and people often don’t know if or when they’re eligible — they might send it in too early, and then feel discouraged” if they are rejected initially, Quirion said.

A better system, she said, would be automatic sealing – a tool that has been adopted by so-called “Clean Slate” programs elsewhere in the country.

“Lots of states have decided to make [sealing] a petition-less process, so you don’t have to do anything,” Quirion said, noting that such programs have been adopted even in states around the country that are more conservative than Massachusetts.

Nina Pomponio, general counsel for the Massachusetts Probation Service, said the office has responded to surging requests for record sealing and expungement by staffing up.

After the 2018 legal changes, Pomponio says, “We had to hire a whole other unit — it even required building out office space for these folks to be able to do this work.”

The work itself is complex, Pomponio says, with each sealing request requiring a seven-step process that includes cross-referencing court files with national databases and can involve digging through ancient court records. Once a petition is successfully completed, Pomponio says, probation staff will seal all relevant records, without a petitioner having to identify each relevant charge.

“All really they have to do is sign their name and give us their identifying information. Our folks then review the record, and we’ll seal anything that is eligible,” Pomponio said.

Pomponio is hesitant, however, when it comes to the idea of automatic sealing and expungement.

“We are absolutely all for sealing and expungement in the sense that it absolutely serves our mission, that we are trying to rehabilitate individuals, assist individuals in achieving long-term positive trajectory in their life and sealing and expungement is a very important part of that,” he said.

“But we have to know exactly what we’re doing when we make it ‘automatic,’” Pomponio cautioned. “I would recommend that we don’t want to do sealing or expungement automatically without the person whose record it is initiating that process.”

For attorney Quirion, though, the positive impacts of such an automatic program would outweigh any negatives — especially for the many clients she sees whose lives are disrupted by old charges that could be sealed.

“It combats racism. It increases jobs for people,” Quirion said. “It’s a win-win.”