On March 10, Silicon Valley Bank in California failed after a run to withdraw deposits, sending shock waves across the nation. It was the country’s second largest bank failure since the 2007-2009 financial crisis. Silicon Valley’s collapse began a chain reaction that prompted customers to pull their money out of Signature Bank, leading regulators in New York to close it. First Republic Bank in San Francisco and others suffered but withstood similar jitters.

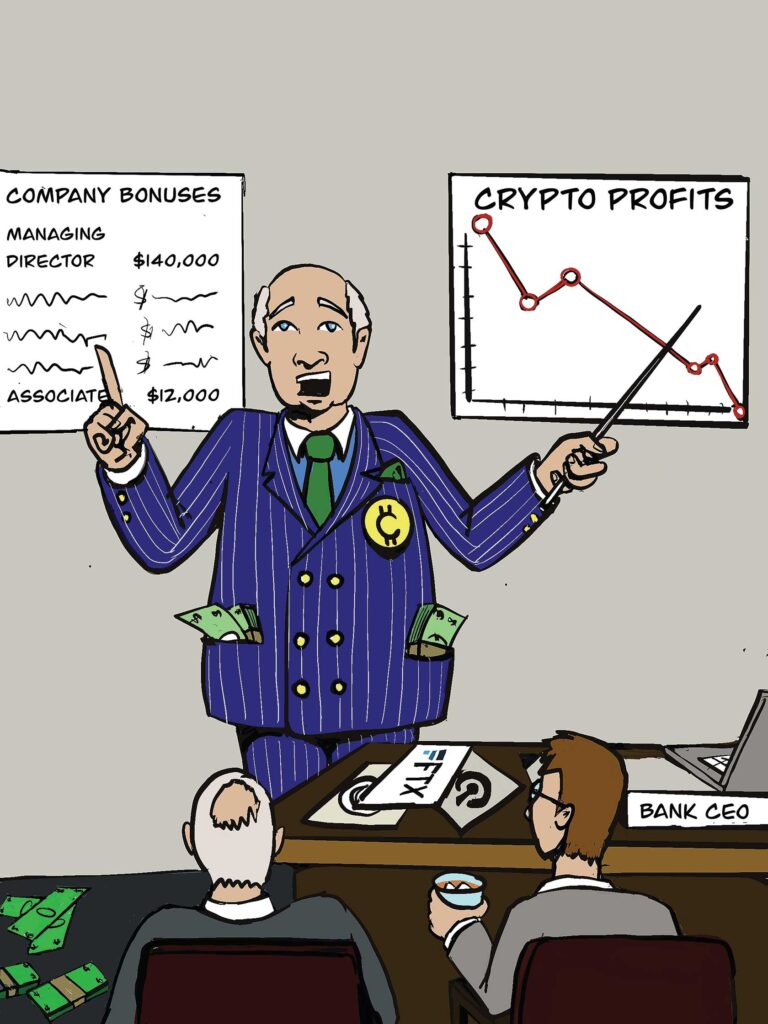

More notable than the Silicon Valley’s demise was the instantaneous blame campaign that Republicans and conservatives mounted. Some members of the party were quick to make wild and absurd claims pointing to “wokeness” as the cause of the banking crisis.

Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri tweeted “SVB = too woke to fail,” using an acronym for the bank. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis insinuated that the culprit was “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” a reference to language on the bank’s website.

Supporting this racist agenda was an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal by Andy Kessler. The columnist suggested: “In its proxy statement, [Silicon Valley Bank] notes that besides 91 percent of their board being independent and 45 percent women, they also have ‘1 Black,’ ‘1 LGBTQ+,’ and ‘2 Veterans.’ I’m not saying 12 white men would have avoided this mess, but the company may have been distracted by diversity demands.”

What Republican critics failed to mention was that in 2018, Trump signed legislation to roll back banking regulations. It removed small and medium-sized lenders from the safeguards of the Dodd-Frank financial reform act, named in part for former Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank. That law was put in place in 2010 in response to the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Removing this protection opened taxpayers to more liability if the financial system collapsed and increased the chances of discrimination in mortgage lending.

Hawley, DeSantis and Kessler apparently did not conduct any analysis of the real causes of Silicon Valley’s failure, such as its over-commitment in the high-tech sector (about 93% of its investments) and an over-leveraged portfolio obtained in acquiring Boston Private Bank & Trust company two years ago. Instead, they chose well-worn tropes insinuating people of color are not competent to run a financial institution, echoing the ugly history of the exclusion of Black Americans from the banking industry from this country’s inception.

Black people have been excluded from the main avenues of American commerce. After emancipation, most freed slaves could not open bank accounts, build credit, own a business or purchase land or a home. In an adaptive response, Black churches, clergy and businessmen banded together to form mutual aid societies, pooling their money to support members of their community and fund local projects.

The federal government created the Freedman’s Bank in 1865, promising depositors their money would be safe and they would be able to eventually buy land and/or a home. Initially, Freedman’s Bank flourished, attracting tens of thousands of customers, but eventually it collapsed due to the looting and mismanagement of its all-white board of directors, whose members ultimately did not care about their Black customers.

The bank’s legacy and failure did create a modicum of financial literacy and inspire a new generation of Black-owned banks. One of the most successful and noteworthy bankers of the early 20th century was Maggie Walker. She was the first Black woman and only the second woman of any race in the country to own a bank. St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia served a membership of more than 50,000 in 1,500 local chapters. Her bank survived the Great Depression and two world wars, helping 600 customers buy homes.

Maggie Walker’s philosophy of banking leaned into Black collaboration, self-sufficiency and independence. She once said: “Let us put our moneys together. Let us use our moneys; let us put our moneys out at usury among ourselves and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

Despite their initial success and ingenuity, Black banks fought against the hostile conditions of systemic racism, segregation and, most importantly, the redlining of Black neighborhoods. Redlining had the most devastating effect on these banks because the mainstream financial system was constantly devaluing loans and mortgages made in their neighborhoods. In the 1930s, a federal agency started the practice of drawing red lines around areas where lending was deemed “hazardous,” raising interest rates on mortgages there or making them unavailable. The practice has since been outlawed. But the damage endures.

Black Americans cannot allow others to label us. Ours is a rich history of resistance and perseverance. History teaches us that when we had nothing, we created something out of nothing to uplift and support each other. Lest we forget.