A bitter legacy: Author Bryan Stevenson on the lasting effects of racism in America

Attorney Bryan Stevenson, who chronicled his defense of the unjustly convicted and condemned in his 2014 bestselling memoir “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” gave a sold-out lecture on March 2 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Bryan Stevenson, author, attorney and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative. PHOTO: ROG AND BEE WALKER FOR EQUAL JUSTICE INITIATIVE

Welcoming Stevenson was Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell, and thanking him after the talk was Boston Mayor Michelle Wu.

Eloquent as a speaker as well as a writer, Stevenson gave a moving, 90-minute talk that included moments of self-effacing humor and poignant anecdotes as he reflected on America’s need to face its enduring legacy of racism.

The recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Award and the ABA Medal, the American Bar Association’s highest honor, Stevenson is a graduate of Harvard Law School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Yet, hinting at earlier roots, his upbringing in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which inspired him to direct his college’s gospel choir, his talk had the cadence and spirit of a homily.

He invoked his grandmother, whose parents had been enslaved. Stevenson described her as “a force of nature” who influenced him to make the most of himself. Raised in a rural town in Delaware, Stevenson recounted experiencing a segregated South as a child and later attending integrated schools. He described a stark experience of racism when, as a 10-year-old en route to Disney World in Florida with his mother and younger sister, they joyfully plunged into a motel pool. Watching angry white adults pull their kids out of the water, he asked a man who had his son by the arm, “What’s wrong?” He replied, “You’re wrong, n___r.”

As founding executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Alabama, Stevenson has won major legal challenges, eliminating excessive sentencing and exonerating 135 innocent death-row prisoners.

Stevenson is bringing the struggle for justice beyond the courtroom, into the public arena.

“At a time when politicians and parents are opposing schools’ efforts to include the history of racial injustice in the curriculum,” he said, “we need our public institutions to be places of truth-telling. We’re not free while our nation remains silently burdened by its history of racial inequality. Toxins don’t go away by being ignored.”

Pointing out the power of arts and cultural institutions to bear witness to tough truths, Stevenson cited the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg and the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda.

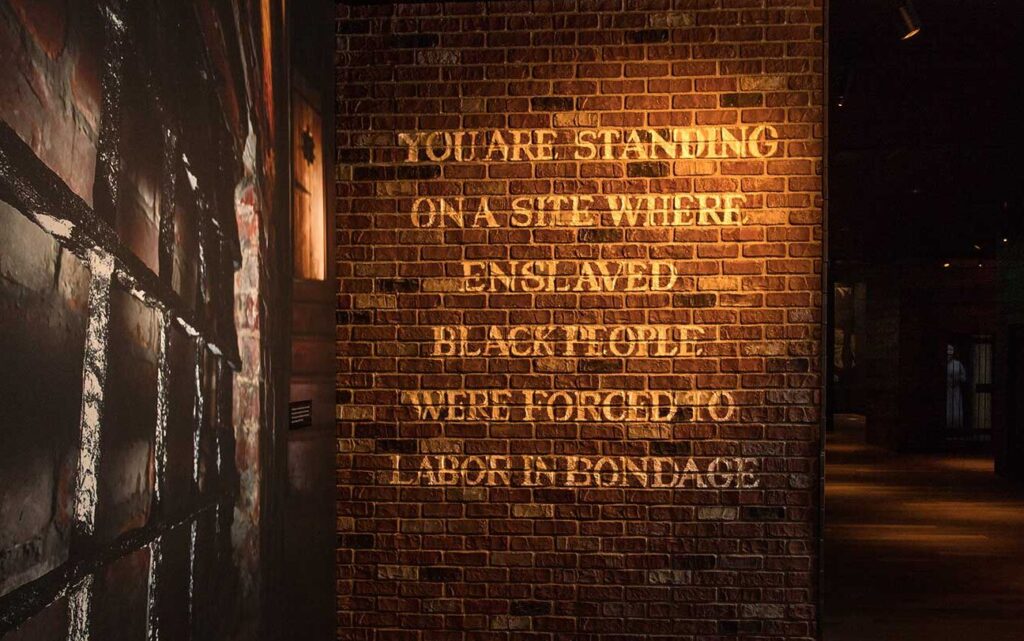

In 2018, EJI opened two such institutions in Montgomery: The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, which immerses visitors in the slave trade, the Jim Crow South and America’s history of racial injustice; and the first national memorial to victims of lynching, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Developed by MASS Design Group in Boston, which also played a role in the new Martin Luther King Jr. memorial in the Boston Common, the memorial displays the names of more than 4,000 African American lynching victims, and with 805 hanging steel rectangles, represents each county where a documented lynching took place.

Urging his audience to “stay hopeful,” Stevenson concluded by saying, “If we can do it in Montgomery, Alabama, we can bring many more people into the struggle to make justice and beauty a reality in our country.”