In 1964, Americans were elated when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. For the first time it became a federal offense to discriminate on the basis of race in employment, education or places of public accommodation. Much less noticed then was the victory in the lawsuit of the New York Times vs. Sullivan that freed print media from damages in hostile defamation suits.

Prior to 1964, the standard to avoid a defamation lawsuit in the press was excessively restrictive. Even the mildest error of little consequence to the story being unfolded could generate substantial damages for the reporter and the publisher. Consequently, politicians and public servants enjoyed indemnity behind a barrier of journalistic reluctance to investigate.

The requirement for the plaintiff in a defamation suit to establish actual malice changed the journalistic dimension. Reporters were suddenly freed to search for truth without being unfairly the victim of a lawsuit. Without this change, the press would have been ineffective in the implementation of the Civil Rights Act provisions.

In fact, the rules that freed the press also created greater attention by newspaper publishers about the accuracy of stories they printed. Carelessness about the accuracy of a story could be evidence against them of actual malice. Persons committed to First Amendment rights generally preferred having publishers responsible for what is published in their papers.

However, the emergence of electronic media created a special liability problem. Print publishers provide static images, while electronic or digital programs are more dynamic. Moving images and not just printed words are involved. So Congress passed Section 230, an exemption from the 1996 Communications Decency Act, that released owners of social media companies from responsibility for the quality of the content that was posted on their platforms.

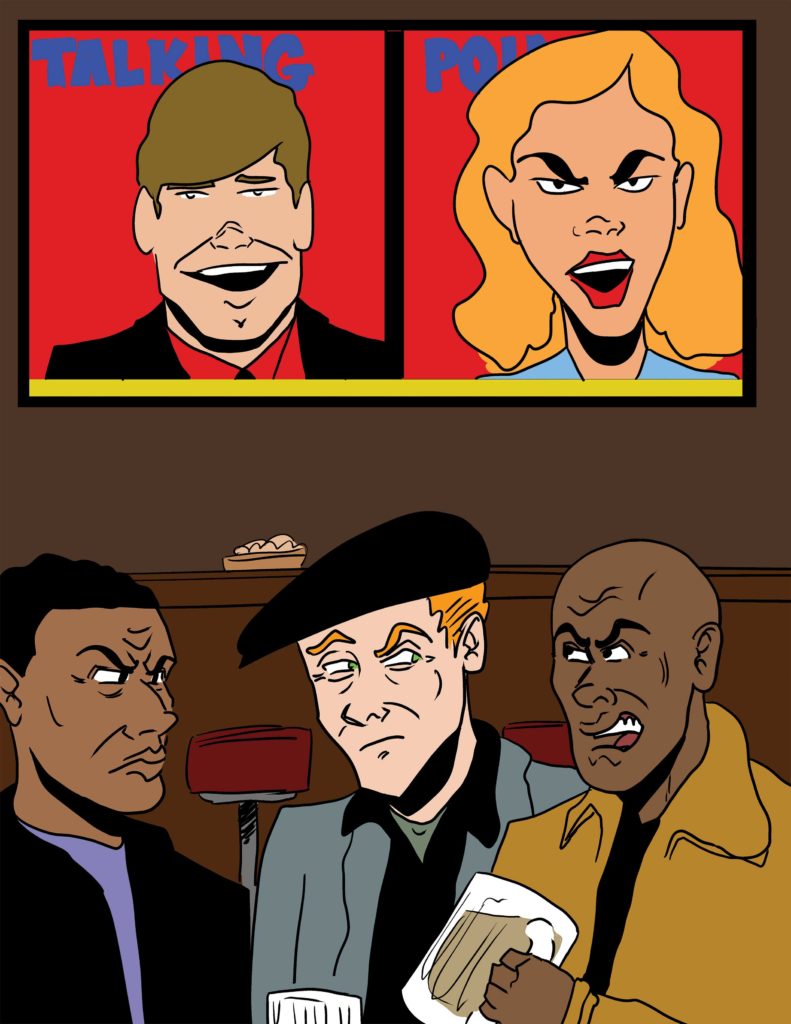

Owners of Twitter, Facebook and any other internet company cannot be liable for the content on their platforms, as would be the publisher of the New York Times. Many Americans who were offended by the torrent of lies on social media during the presidential campaign in 2020 do not want to reprise that state of affairs in 2024. But the internet media is expected to battle for the continuation of the Section 230 rule.

Now that Donald Trump is back on Twitter and will soon be on Facebook and Instagram, many Americans are concerned about the use of the digital media to communicate fallacies. Of course, what citizens hear from the media companies are vainglorious comments about their commitment to protect the American principle of the First Amendment.

There is little reason not to believe that the view of the media moguls is to maximize advertising revenue. They know that the purpose of the First Amendment is to prevent the government from interfering with free speech. It contains no impediment on restrictions private companies might impose. Indeed, who would object to internet media restrictions that would require political advertising to be accurate?

Voters should understand that the presidential campaign for 2024 has already begun. America almost lost its democratic system in the aftermath of the last presidential election. It is time to repeal Section 230 and establish tough standards for veracity in publications and internet media communications that inform citizens of government issues.

The American judiciary has enabled journalists to uncover the truth of official actions without fear of legal recriminations. Now it is time for Congress to require that the truth be told.