When John Adams died in 1826, his library was a marvel. The second president of the United States amassed much of his collection while serving as a diplomat in the Netherlands, Spain, England and France. Adams, who spoke eight languages, amassed an impressive 3,000 volumes at a time when the Library of Congress had fewer than 800 volumes.

A first-edition copy of David Walkers Appeal. BANNER PHOTO

Today his collection sits among the 22.7 million volumes in the Boston Public Library. But it’s no less a treasure than it was 200 years ago. The leather-bound volumes occupy a portion of the windowless, climate-controlled Special Collections stacks buried near the center of the building — a concrete bunker-like structure where the temperature is a constant 65 degrees.

The stacks are the core of the Boston Public Library’s newly renovated Special Collections facility, which includes 240,000 rare books as well as rare manuscripts, newspapers, prints, photographs, maps and other historic objects. The two-level facility is opening this week after a five-year, $16 million renovation project.”

A glassed-in elevator accessible from the lobby of the Johnson Building, which faces Boylston Street, opens into a foyer. The special collections reception room lies behind glass doors and is lined with climate-controlled glass display cases on two walls. A reception desk fronts a wall made of copper and covered with glass. To the left, a glass wall provides a view into a display room on the first level and the stacks on the second level.

“You’re standing within what’s essentially a library within a library,” said Beth Prindle, head of Special Collections. “For us, this is a transformation of how we serve the public through special collections.”

John Adams’ collection in the BPL Specia

In years past, visitors who wanted to view objects in the Special Collections requested them from a librarian, who then brought the objects from the bowels of the library to a viewing room. While the process is very much the same, much of the collection is now visible, with windows in the reception and display rooms open to the viewing rooms and a special lab where objects from the collections are restored.

Patrons will be required to leave their bags, coats and any packages in the reception area and wash their hands (to remove oils or sweat) before handling any of the materials from the collection. The room where patrons are allowed to view the materials consists of several rows of tables surrounded on two sides by a wooden card catalogue.

“This is an important part of our history,” Prindle says of the catalogue. Cards from the cabinets have been scanned and digitized, as have much of what appears in the special collections.

Highlights of the collections include:

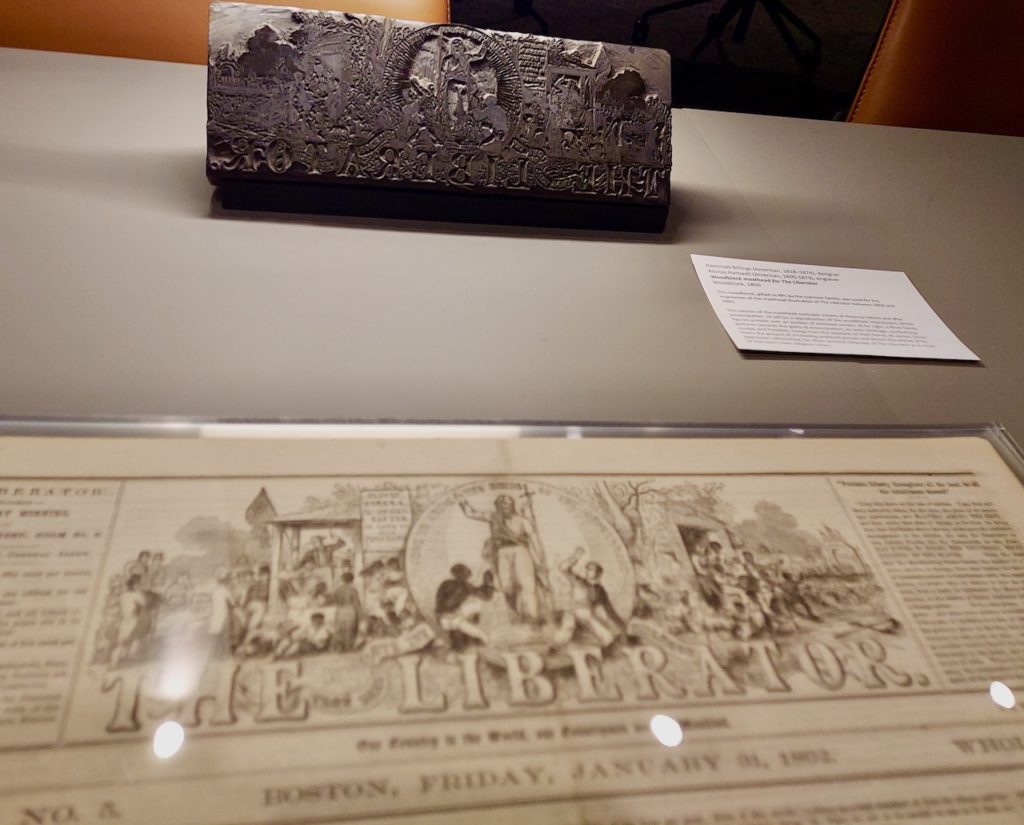

- The entire collection of The Liberator, the abolitionist newspaper published by Roxbury resident William Lloyd Garrison between 1831 and 1865. The collection also includes Garrison’s correspondence.

- A first-edition copy of David Walker’s “Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Colored Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America,” an anti-slavery pamphlet that was banned in southern states and help stoke anti-slavery passions across the United States.

- The library of Wendell Phillips, a Boston abolitionist and advocate for Native American rights.

- One of just eight first-edition copies of William Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Drlso eam,” printed in 1600 and acquired by the library in 1873.

- The correspondence of George W. Forbes, a librarian and co-founder with William Monroe Trotter of the Guardian Newspaper. The collection includes letters exchanged between Forbes and W.E.B. Du Bois, poems Forbes wrote and research he conducted on the life of David Walker.

- The former library of the Old South Church, for which Boston Public Library has served as a custodian since 1966.

Other items in the collection include prints and sketches by artists, sports paraphernalia, historical maps, original scores by Mozart and George Washington’s Congressional Medal of Honor, as well as photographs and artifacts from Boston’s history, such as a teapot said to have been owned by Crispus Attucks.

The renovation began after a 2015 incident where two rare prints were thought to be missing from the collections. While the prints were later found to have been misfiled, the scandal came after an audit of the Special Collections that was sharply critical of the way they were managed.

In the newly-renovated space, the books and artifacts are cared for in a state-of-the-art lab, where specialists make repairs to book covers and bindings using adhesives that will not further damage the items.

“The goal is only to stabilize, rather than return something to a version of its original condition,” said Jessica Bitely, the library’s preservation manager.

Arguably, the heart of the collection is the stacks, with the libraries of Adams and other notable 18th- and 19th-century intellectuals preserved in a low-humidity, temperature-controlled 31,000-square-foot space. A narrow staircase leads up to the fortress-like chamber, with low ceilings, no exterior windows and a gas-based fire suppression system backed up by sprinklers that can target a specific area where fire is present.

Among the collections in the stacks is that of former Harvard professor and literary critic George Ticknor (1791-1871), who amassed an impressive collection of Spanish and English literature.

“This is one of the great libraries of the 19th century,” Prindle says, pointing out the rows of steel stacks now occupied by Ticknor’s books. Other great collections among the stacks are those of Unitarian minister, transcendentalist and abolitionist Theodore Parker (1810-1860) and mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch (1773-1838), whose collection includes rare scientific texts written by Sir Isaac Newton and Galileo.

For sheer historical significance, Adams’ collection stands out. Much of it was acquired while he served as a statesman in the Hague and in France, where he collected more than 500 volumes.

Detail from a first-edition printing of A Midsummer Night’s Dream from 1600. BANNER PHOTO

Adams’ books, many of which travelled with him across Europe and the United States, convey history.

“These books were sitting in the White House,” notes Prindle.

Beyond their intrinsic historical value, Adams’ books hold insights into how the books he read influenced his thinking, as many bear his notes, scribbled with a quill pen in the margins.

“You can look at what he was reading, and what he thought about what he was reading,” Prindle said.

Like most volumes in the special collections, Adams’ books are viewable online. But for those who prefer to leaf through the actual books, they can again be viewed in person. Just be sure to bring a sweater.