When the BRA leveled a Lower Roxbury neighborhood

Campus High plan called for mega high school, leveled a neighborhood

Up until the late 1960s, the area of Lower Roxbury around Madison Park was a vibrant neighborhood where luminaries such as jazz drummer Roy Haynes, former state representative and Minister Michael Haynes, Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan and former Boston Police Superintendent William Billy Celester came of age.

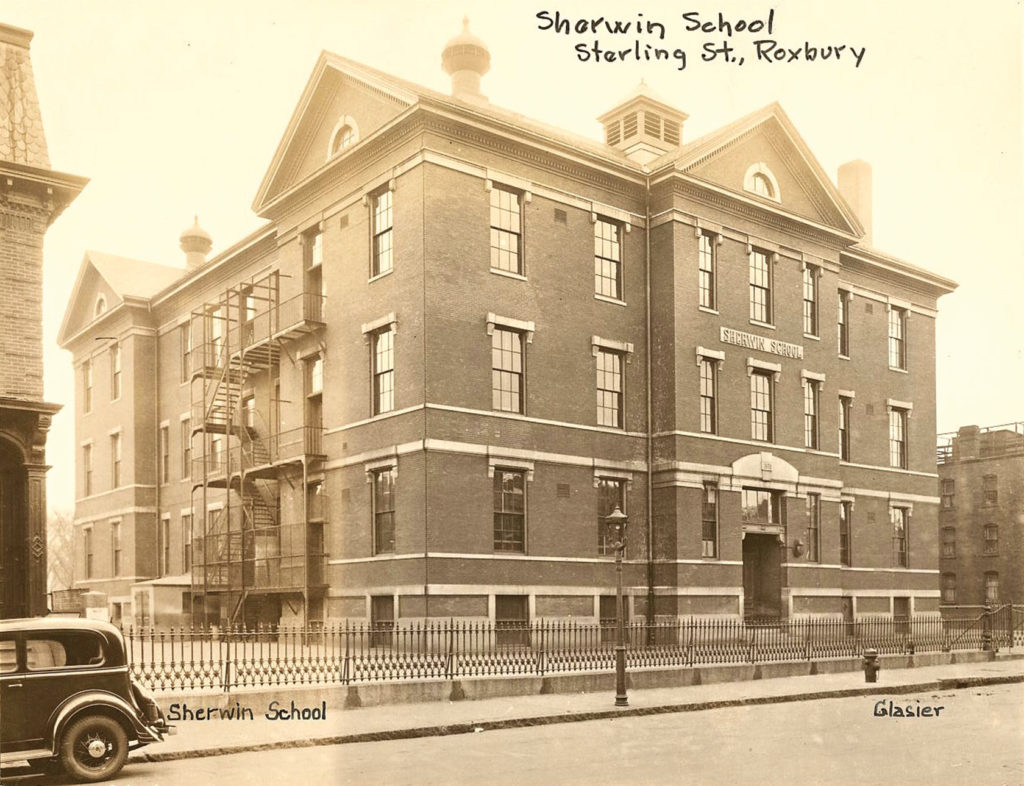

But a plan that was hatched in 1962 would soon wipe the neighborhood from the city’s map, erasing the park that gave it its name, along with school buildings, homes and streets that were steeped in Roxbury history.

The end goal was an education complex that would consolidate all of the city’s high schools, save Boston Latin School and Girl’s Latin School, into one campus with shared athletic fields. Driving the vision for the new campus was newly appointed Boston Redevelopment Authority Director Ed Logue.

In 1962, Logue recruited a group of students at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education to come up with a plan for school redesign — a ’60s version of BuildBPS. Their plan called for the construction of 60 new elementary and middle school buildings across the city over a 10-year period and the construction of the campus high complex with space for 5,500 students.

A Boston Redevelopment Authority map shows the Madison Park Urban Renewal Area with a high school complex that was meant to house all 5,500 Boston students not in exam schools.

“There are, then, powerful and practical educational reasons for the creation of a single, large high school providing each of its students with the facilities and the education program he or she should be receiving,” the graduate students wrote in their May 1962 report.

Then-Mayor John Collins and School Superintendent William Ohrenberger supported the plan.

Then, as now, high schools of different sizes were scattered across the city’s neighborhoods — Dorchester High, South Boston Hyde, Hyde Park High, Roxbury Memorial, Charlestown High.

The idea of a unified school complex was not unheard of. Cambridge underwent a similar process. In 1977, the city’s two high schools, Rindge Tech and Cambridge Latin, merged into one building complex.

In Boston, the plan called for a 50-acre campus.

While that sounds unimaginable to Bostonians today, in the 1960s, the BRA’s urban renewal schemes had wrecking balls in full swing. City officials considered parcels of land in the West End, in Forest Hills, on Mt. Vernon Street in the Columbia Point section of Dorchester and, finally, in the Madison Park neighborhood of Roxbury.

In Logue’s eyes, the neighborhood was ripe for the kind of demolition and redevelopment that the BRA had honed in the West End and the New York Streets and Castle Square sections of the South End.

At the same time, then-Gov. Francis Sargent had secured federal funding for an ambitious highway project that would have extended Interstate 95 through Milton and Boston, connecting it to an inner belt highway that would have arced from the site of the current Massachusetts Avenue exit on Interstate 93, through the South End and Fenway neighborhoods, through Central Square in Cambridge and Somerville to connect with the elevated expressway.

“At that moment, the car was king,” said Karilyn Crockett, whose book “People Before Highways” chronicles the campaign that ultimately put a stop to the highway project. “There were so many cities that were struggling and losing population. Highways were thought of as a way to bring money back into your city — to bring people in to shop or work.”

A 1930 map showing the park that gave the Madison Park neighborhood its name. BPDA archive

As was the case in other major cities, Boston’s population was declining from its high of more than 800,000 in 1950 to an eventual low of 562,000 in 1980. Logue’s charge, as director of the BRA, was to make the city’s real estate more valuable. Slum clearance was the means. The federal government gave quasi-governmental redevelopment authorities such as the BRA extraordinary powers to declare neighborhoods slums and the funding to tear them down.

But there at the intersection of planned highways and planned slum clearance, Logue met some formidable adversaries. A group called the Lower Roxbury Community Coalition (LRCC) came together to fight the BRA and its urban renewal plan, which many in the community referred to as its “negro removal.”

Former state Rep. Byron Rushing, then an organizer with a group called Roxbury Associates, worked with the LRCC co-chairs, Ralph Smith and Shirley Smolinsky, to fight the BRA.

“Many people in Lower Roxbury, even homeowners, had just given up,” he said. “They really thought they were losing their homes.”

The destruction of the West End and the New York Streets area were still fresh in people’s minds. Rushing said the BRA’s release of an urban renewal map showing the campus high project set people off.

“It looked like they wanted all of Lower Roxbury,” he said.

To the north, the proposed inner belt highway would eventually claim more than 2,000 housing units. Melnea Cass Boulevard currently occupies the right of way secured for that section of the highway. To the west, the Interstate 95 extension was envisioned as an eight-lane highway that students would cross on pedestrian overpasses. Both corridors were cleared of the houses and business districts that lined their streets.

As community outrage grew, organizers including Rushing, the late Chuck Turner, Alex Rodriguez, the late Vinny Haynes and Syvalia Hyman were able to convince more and more residents that they could fight back and take control over the plan.

By the early 1970s, community members’ demands that any homes in the neighborhood that were demolished be replaced with new units was gaining traction. At the same time, the political reality in Boston had changed.

“There was the increasing segregation in neighborhood schools and the intransigence of the Boston School Committee to open up schools for desegregation,” notes Richard Heath, a Jamaica Plain-based historian and journalist. “On top of that, you had a change of mayoral administrations.”

Also, the administration of President Richard Nixon cut funding for urban renewal, giving the BRA less to work with.

While community organizing in the Castle Square area had helped convince BRA officials to build city-owned public housing there, in Madison Park, the community was given a new tool: the community development corporation. In 1967, the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation in Brooklyn became the first CDC incorporated in the nation and received $7 million in federal funding for redevelopment in that neighborhood.

In Castle Square, Rushing said, community members took things a step further, demanding that they be given the power to plan and develop housing on the land. Under Mayor Kevin White, they were given that guarantee. In Lower Roxbury, the LRCC changed from a community organizing project to become the entity now known as the Madison Park Development Corporation.

A Haskins Street home that was demolished in the early 1900s. City of Boston photo archive image

“All the homeowners lost their homes,” Rushing noted. “But everybody got housing. Nobody who wanted to stay had to leave.”

When Heath, the historian, arrived in Boston in 1973 after serving two tours of duty in Vietnam, the Madison Park area appeared as a wasteland.

“You could come out of Dudley Station, walk a block and it was utter devastation,” he said.

Yet images of the area by renowned Boston artist Alan Rohan Crite depicted a vibrant community, Heath notes. When the community members contracted with architect John Sharratt to build out the Madison Park development, they sought a design that honored that community, he said.

The CDC began with the 132-unit Smith House, named in honor of organizer Ralph Smith, and the 131-unit Haynes House, named for Vinny Haynes. The townhouses in Madison Park Village were completed in two phases, 120 units in 1978 and 143 units in 1980. The CDC has also renovated and developed units on Shawmut Avenue, Melnea Cass Boulevard, Kenilworth Street and elsewhere in Roxbury, Dorchester and the South End.

By 1978, the Campus High plan had fizzled. The city was by then under a court-ordered desegregation plan, and the Madison Park campus was just a small part of it. The new high school building housing Madison Park High School and the Humphrey Occupational Resource Center — a trade school — was said to be the largest school building east of the Mississippi River. But no major school mergers were in the offing.

Madison Park is now a vocational technical school and occupies the space built for the Humphrey Center. The John D. O’Bryant School — an exam school — moved into the portion of the complex that originally housed Madison Park. The Madison Park Development Corporation’s Madison Park Village occupies the rest of the area cleared by the BRA.

The buildings in and around Madison Park Village stand as a sort of testament to the will of the organizers and community members who fought for people to stay on the land. Their accomplishment, during an era where city planners often saw residents as an impediment to progress, was extraordinary, according to Crockett.

“It was revolutionary for people to stand up and say no to a highway but also yes to the people who live here,” she said.