Colombian soccer star was national hero

Shone on country’s team during time of rising crime, political strife

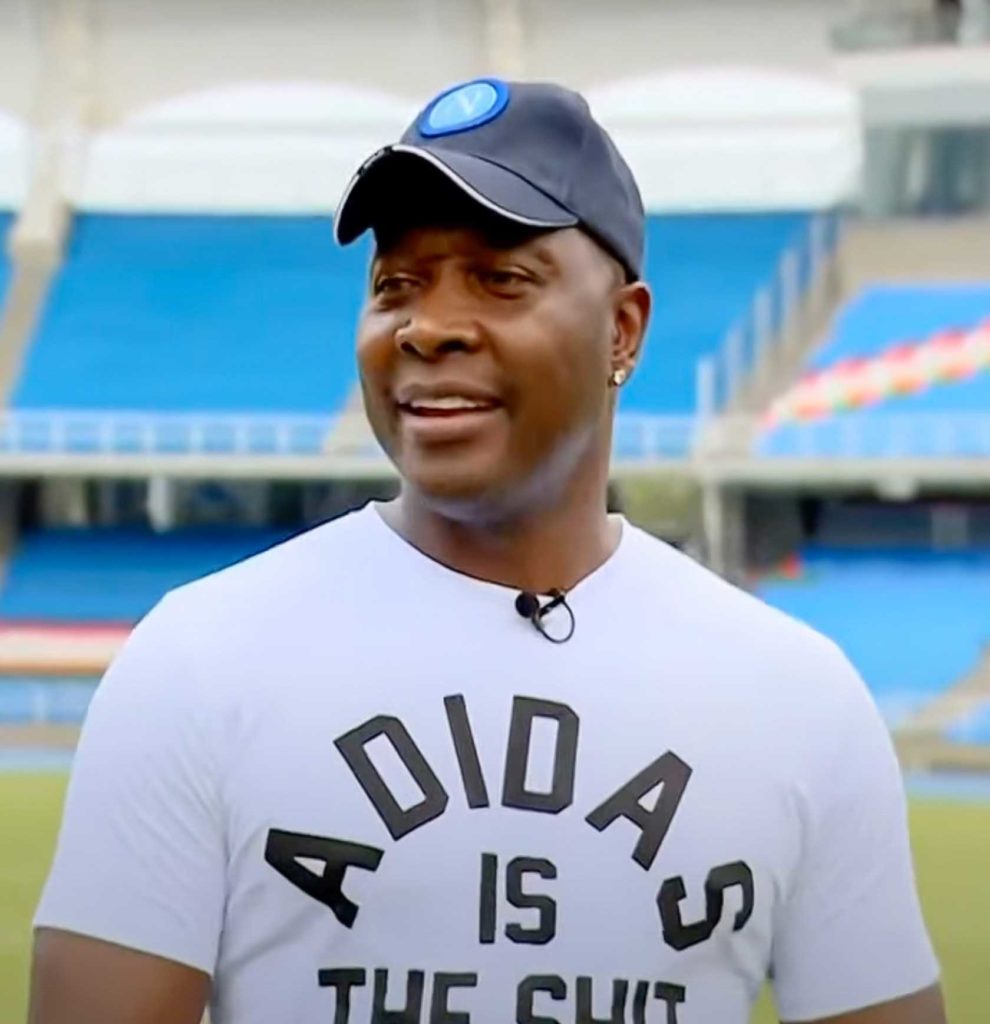

Colombian soccer player Freddy Rincon is forever linked with one of the most rapturous moments in the history of his resource-abundant but historically-turbulent country.

His extra-time goal against Germany in the 1990 World Cup staved off first-round elimination. The goal also raised the morale and conviction of a nation resolutely opposing the ghastly brutality of narco-trafficker Pablo Escobar and other vicious cocaine cartels.

With time nervously ticking away from Los Cafeteros, Rincon’s exquisite strike ended a last-minutes rollercoaster of emotions. A 0-0 score would have sufficed, enabling Colombia to advance to the next round. But super sub Pierre Littbarski’s 88th minute goal made it 1-0.

Colombia, now suddenly on the verge of defeat, found a tying score four minutes later, setting off a delirium still talked about as the singularly-greatest sports moment in the country’s history.

Freddy Eusebio Rincon Valencia died April 13 in a car accident that occurred several days earlier in the early morning hours in Cali. He was 55. The cause of death was traumatic brain injury.

The accident galvanized the 50-million-strong predominantly Catholic countrymen, who held a prayer vigil for the five days Rincon lay in a coma. It also hit hard in Brazil, where he played for three teams and was a World Cup Club champion, captaining Sao Paulo giant Corinthians in 2000 to the title.

“First of all, it was very hard for the people, the Colombian community and soccer fans, because he was an icon after that goal in Italy against Germany in 1990,’’ said radio presenter Marino Velasquez, a native of Pereira and a voice of Colombian news in Boston for the past 32 years at 1600 AM “Deportes y Mas.”

“After that the way he treated people and carried himself, never getting in trouble with the authorities or anything,’’ added Velasquez. “He was an impressive guy. He was (6 feet, 2 inches) tall and all muscle but very humble. He was always eager to talk to the media. No problem. He didn’t have a problem with anybody.’’

Velasquez, who regularly has returned to Colombia for all the team’s big matches and events, has covered three World Cup tournaments, three South American championships and almost all of the important qualifying games, as well as USA national team and MLS games.

Rincon was the driver in the early-morning crash and three other occupants in the vehicle survived He was sideswiped by a bus at an intersection. The bus driver and a companion originally fled the scene. Velasquez said the risk of getting robbed at those hours in some areas of the city prevents motorists coming to complete stops at red lights or stop signs.

“I don’t want to criticize my country, but it is the truth. You take a risk at that hour, and you can get robbed,” he said.

“Unfortunately, he wasn’t wearing his seatbelt properly,’’ added Velasquez. “He only had the strap at his waist fastened. He didn’t fasten the upper part. After the autopsy, the coroner confirmed he was the driver after they took the information from the emergency relief people who arrived on the scene.’’

Rincon played in three World Cups and three South American championships for Colombia. He was part of a stunningly-good generation of players that included Carlos Valderama, Rene Higuita, Leonel Alvarez, Faustino Asprilla and others.

National morale

To appreciate just how important the team became to the country is to remember what Colombia had been going through since decades earlier. Guerilla movements from the left began fighting the government and occupying large tracts of land in their effort to, in their words, protect the poor and perhaps introduce communism.

Far-right groups, the paramilitary, backing the government fought the leftist groups, the most popular being the FARC. Over the decades more than 200,000 people allegedly died in the conflicts.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the cocaine cartels became all-powerful. When Pablo Escobar was killed in 1993 by special military forces, his perceived worth was $30 billion, as cocaine euphoria in the 1970s and 1980s swept the United States and Western Europe.

“That was a very hard time for the country, with all the drugs and the violence and the bombs that were around because of Pablo Escobar and the drug dealers,’’ said Velasquez. “That was a hard time for Colombia. They were all around and then they got involved with the Colombian soccer team.’’

Drug money tainted most aspects of society, and when they stood for their country’s very survival, judges, lawyers, newspaper editors, reporters, elected officials and normal citizens were routinely murdered. So when ESPN showed members of the Colombian team playing soccer at Pablo Escobar’s compound, it was perhaps a case of an offer they could not refuse.

The reign of terror and absurdities seemed to have no finality. The remainder of the 1989 soccer season was cancelled when a referee was killed in Medellin. Still, the Colombian team managed to qualify for the 1990 World Cup and put on an excellent display before bowing out to Cameroon in the Round-of-16.

Colombia, in the coming years, took the world by storm, defeating Argentina 5-0 in Buenos Aires to qualify for USA 1994. Rincon scored twice in that game with a retired Diego Maradona watching from the stands recognizing his return to his country now was vital if Argentina would ultimately qualify via a playoff.

Meanwhile, Argentines, in the full stadium, showered the Colombian team with a respectful and prolonged standing ovation.

In all, Rincon scored 17 times in 84 games for Colombia and had 162 career goals at club level for various teams in 627 matches. This was all done while providing a solid all-around role in midfield.

Colombia was flying high. Even Pele said the team could be world champions. But the much-hyped Colombia team stumbled in the USA-hosted tournament, losing to Romania and the United States before beating Switzerland and then heading home.

The unimaginable pressure, however, was omnipresent. While in the U.S., death threats back home were made against the team if midfielder Gabriel Gomez was inserted in the lineup against the USA. Coach Francisco Maturana, recognizing the threats then were tantamount to death sentences, left the veteran out of the team to ensure everyone’s safety.

Even that didn’t seem to matter. In that game, the quietly efficient central defender Andres Escobar slid to cut out a cross into the Colombian area by the USA’s John Harkes. The ball deflected off him into his own goal. Escobar, days after returning home, was gunned down in Colombia, perhaps by some gambling elements.

Unforgettable

It was in this grisly environment that the team became a palliative. Leonel Alvarez, who played here in Boston for the Revolution in 1999-2000, was a high-quality guy, and Maturana’s team had many solid role models.

Rincon was involved in a scandal with a sketchy Panamanian in 2007 and was held for 124 days in Brazil for alleged money-laundering. He later cleared his name, showing his investments all came from his earnings as a soccer player. His move to Real Madrid in the mid-1990s, for various reasons, did not work out. But his importance to his country and his timely goal could never be overstated.

“Yes, I remember that goal like it was yesterday,’’ Velasquez said. “I was living in an apartment on the second floor and my brother left the game a few minutes before, thinking we had lost. By the time he got downstairs, I started to scream because of the goal. He was back so fast in the apartment with me. It was like he jumped from the parking lot through the window and was standing in my living room. That’s my greatest memory from the Colombian national team.’’