Education commissioner launches second BPS audit

Again, schools face threat of receivership

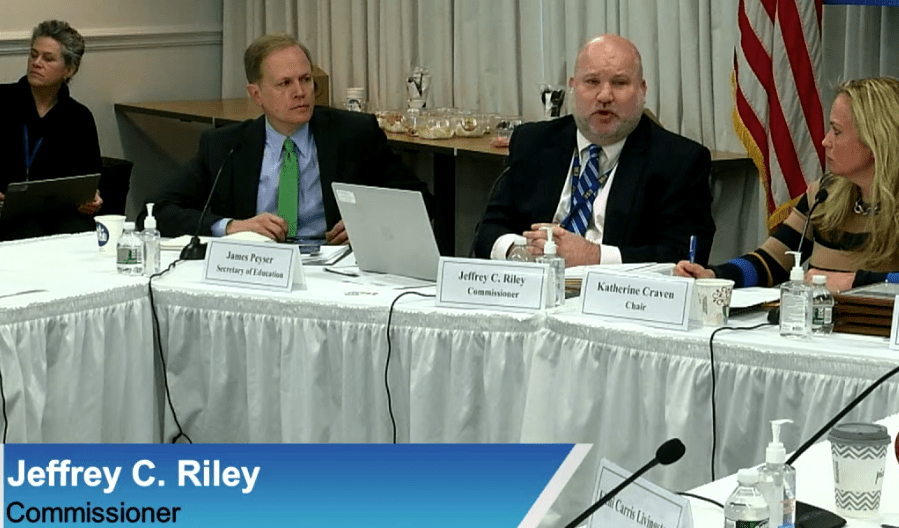

On March 9, Massachusetts Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Jeffrey Riley fired off an email to Boston Public Schools Superintendent Brenda Cassellius informing her his office will conduct a district review — an audit of the city’s public schools — citing late buses, the concentration of students of color in special education classrooms and other unspecified concerns.

Hanging over BPS is the threat of receivership, an aggressive state intervention in which the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) assumes control of a district, replaces the superintendent, effectively superseding the authority of the mayor and school committee. The move, in effect, takes away local control of the schools.

The audit is a first step in the process.

The Riley originally ordered an audit in 2019. That audit pointed out that there are 34 BPS schools that the state ranks in the lowest 10% of public schools. Under the ranking system, based primarily on students’ scores on the state’s MCAS exam, schools in the lowest-income communities in Massachusetts generally rank in the lowest 10%.

Critics of the ranking system point out that low-income school communities, such as Boston, where 71% of students are considered low-income, also shoulder a disproportionate percentage of English language learners and students with disabilities, and therefore, are more likely to face some form of state receivership.

Currently, the state has the school districts of Lawrence, Holyoke and Southbridge in receivership, all of which are low-income communities. Under state control, none of these districts has yet moved out of the lowest 10% in the ranking system. Lawrence, a district in which 88% of students are classified as low-income and 71% are classified as English language learners, just 21% of students scored “meeting expectations” or higher on the MCAS math exam in 2021, despite more than 10 years under DESE receivership.

As the COVID pandemic was grinding Boston to a halt in March, 2020, Cassellius signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with DESE, pledging to make progress on reforms to Boston’s schools, including making improvements to the 34 schools the state labeled “underperforming,” expanding access to advanced coursework, reducing student absenteeism, reducing the number of students with disabilities in separate classrooms, fixing bathrooms that were in disrepair and increasing the on-time arrival of school buses.

Before the audit, then-Mayor Martin Walsh had committed to increasing funding in the $1.3 million BPS budget by $100 million as part of Cassellius’ plan to make improvements to the district.

But as the ink was drying on the MOU, schools across the state went remote in response to the COVID pandemic. During remote learning, BPS officials were able to make some progress, including repairs to school bathrooms and upgrading drinking fountains. Progress on MCAS exam scores was hampered by the state’s cancellation of the test in 2020 and by remote schooling, which limited how much instruction students were able to receive.

In September of last year, however, Matt Hills, a member of the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, floated the idea of receivership for the city.

Riley told Hills the matter was not on the agenda, but added, “I would also say it’s a process we want to go through and, to be continued.”

On March 7, 2022, just two days before Riley notified Cassellius of the DESE audit, the conservative-leaning Pioneer Institute, a group which advocates for privatization of public education, released a report recommending receivership for Boston’s public schools, citing factors including the underrepresentation of children of color in the district’s three exam schools and what it said are long waitlists for charter schools in the city.

“Boston’s schools are failing most students,” said Cara Candal, author of the study. “The district has had generations to turn around chronically low-performing schools, and despite modest pockets of progress, it has been unable to sustain even small improvements.”

What’s next?

Local education activists have already begun to mobilize against a state takeover of Boston’s schools. The Boston Teachers Union this week launched a letter-writing campaign to state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) members arguing the state should meet its funding obligations to the district under the Legislature’s Student Opportunity Act, rather than plan an intervention in BPS.

Under the 2019 education law, the state was required to increase funding for special education. The state has not yet met those funding obligations. Without significant additional funding, it’s not clear how the district could create more inclusion classrooms — classes where students with disabilities are educated alongside regular education students.

“What we need is resources and stability, not receivership,” Boston Teachers Union President Jessica Tang told the Banner.

There are several factors that could make it difficult for the state to put BPS in receivership. For one, while there are 34 schools that are in the lowest 10% of DESE’s rating system, the Boston district as a whole is not in the lowest 10%.

The district may also be too large for DESE to run. Given its poor track record in Lawrence, Holyoke and Southbridge, it’s not clear how DESE could effect positive change in Boston.

“Southbridge and Holyoke are the worst-performing and second-worst performing districts in the state, by DESE’s most recent rankings,” noted at-large City Councilor Julia Mejia, speaking during the BESE meeting Tuesday morning.

Mejia also noted that Lawrence, a district where Riley himself served as state-appointed superintendent, is ranked in the lowest 6% of schools in the state.

The timing of the intervention may not favor Riley, who was appointed education commissioner by outgoing Gov. Charlie Baker. The next governor, whether a Democrat or Republican, is likely to appoint a new commissioner. Whatever plan Riley puts in place may take a different turn under the next administration.

Yet the process appears fast-tracked. Normally, districts are given a six-month lead time before an audit. Riley’s letter gave BPS just two weeks and has forced the district to postpone for a week its scheduled administration of the MCAS exam.

Mayor Michelle Wu testifies at the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education in Malden.

One option DESE could pursue is an intervention into the 34 schools it considers low-performing. The agency has taken that approach in Springfield, where it has established what it calls an “empowerment zone,” a cohort of 17 schools serving 5,300 students. While DESE does not list the ranking of that zone as a whole, results for the schools appear mixed. At Kiley Academy, for instance, just 17% of sixth-graders met or exceeded expectations on the 2021 English Language Arts MCAS exam. At the Chestnut Accelerated Middle School, 42% met or exceeded expectations, much closer to the state average of 47%.

Riley may also use the threat of a partial or full takeover of the schools to influence the administration of Mayor Michelle Wu in its pick for the school district’s next superintendent. Riley said in his letter that he expects the DESE review to “provide important information for a new incoming BPS superintendent.”

Speaking out against receivership during the BESE meeting Tuesday, Wu said she looked forward to working with the School Committee and the search committee she has appointed to identify superintendent candidates. She said her administration will commit resources to improving school facilities and providing wraparound services for students.

“No one is better equipped to accelerate the progress Boston has made than our Boston Public Schools communities,” she said, “and I’m confident that this review will suggest the same.”