Sex trafficking law has a racist past

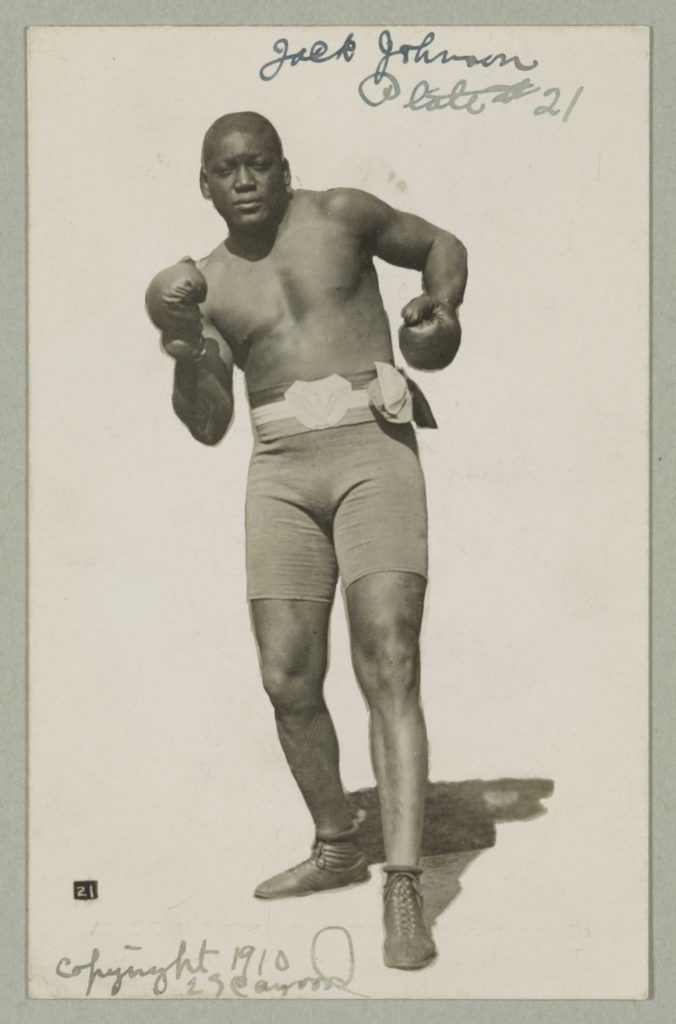

Mann Act first deployed against heavyweight champion Jack Johnson

The mounting federal sex-trafficking case against prominent Trump apologist Matt Gaetz, a right-wing Florida congressman accused of luring underage girls across state lines, has an unexpected link to Black history.

The charges Gaetz could face draw upon a legal statute, the Mann Act, first deployed to unjustly prosecute Jack Johnson, the world’s first Black heavyweight boxing champ.

Johnson’s persecution under the broadly drawn measure reveals more than America’s troubled history of racial anxiety. His saga is an early data point in our national examination of the criminal justice system. Jack Johnson is one in a long line of Black Americans to challenge the status quo only to find themselves pursued by the law.

Johnson drew condemnation by openly consorting with white women, some of them of dubious virtue and three of whom he would go on to marry. In Chicago, he opened a mixed-race night club — Café de Champion — doubling down on his critics’ core complaint.

This was the era of public lynchings, when displays of vigilante violence enforced racial apartheid. American audiences of the emerging film industry were watching “Birth of a Nation” depict interracial relationships as de facto rape. Black people, and especially Black men, were simultaneously economic and romantic threats to the pre-World War I American patriarchy of 1910. Jim Crow had settled in across America.

The pursuit of Johnson came more than a decade before an innocent remark by a Black teenager to a white girl on his elevator sparked a race massacre in Tulsa, two decades before Billie Holiday sang “Strange Fruit,” a chilling evocation of lynching, and 45 years before Chicago teenager Emmett Till, on a visit to family in Mississippi, was brutally murdered for an imagined whistle to a white woman.

During the peak of Johnson’s boxing career, the U.S. Attorney based in Chicago, Edwin Sims, was waging a war on “white slave traffic.” In a self-published treatise on the topic, Sims depicted himself as the “man most feared by all white slave traders.” Sims argued Congress should let federal agents, a precursor to the FBI, combat interstate human trafficking. The 481-page booklet suggested the legislative language for what would become the Mann Act.

Chicago Congressman James R. Mann chaired a powerful committee on interstate commerce. Over six months in 1910, Mann shepherded his namesake bill swiftly into law. The Congressional Record immortalizes Sims’ influence on the Mann Act debate, which appears under the heading: White-Slave Traffic.

Two years earlier, before Mann pushed his legislation through Capitol Hill, Jack Johnson had won his first heavyweight title, handily dispatching Canadian Tommy Burns. Johnson fought Burns after years calling for a title fight against reigning champion Jim Jeffries, who had retired rather than fight a Black man. In 1910, Jeffries, the first so-called “Great White Hope,” emerged from retirement only to lose to Johnson in an outdoor bout in Reno, Nevada witnessed by thousands. Riots broke out when Johnson’s hand was raised in victory.

Two years later, Sims launched an investigation of Johnson’s interracial relationships and made the boxer the first defendant to face Mann Act charges. By then, Congressman Mann had been elevated to House Minority Leader.

In retrospect, Johnson’s 1912 charges should come as no surprise. The federal prosecutor handling the case was Sims’ protege, Assistant U.S. Attorney Harry Parkin. After Johnson’s conviction, Parkin’s twisted judgement was quoted in The Indianapolis Freeman newspaper: “This Negro, in the eyes of many, has been persecuted. Perhaps as an individual he was. But it was his misfortune to be the foremost example of the evil in permitting the intermarriage of whites and blacks.”

To Sims and Parkin, Johnson loomed as a threat to the received order. He strode upon the world stage, confident and strong, dressed to the nines and often with a white woman on his arm. He refused to accept the economic and social strictures imposed upon Black people. His unabashed defiance of contemporary racial norms is why the Ken Burns documentary “Unforgivable Blackness” would describe Johnson as “the most famous — and most notorious African American on earth.”

But the trouble with Sims’ charges was that Johnson wasn’t engaged in human trafficking. Rather, the mother of his soon-to-be wife, Lucille Cameron, complained to police about her daughter’s consensual relationship with a Black man. That was all the pretext prosecutors needed to go after Johnson.

The case would fall apart when Cameron refused to cooperate. But, in 1913, Johnson was re-arrested and charged. The 1913 trial was overseen by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis — the future baseball commissioner who kept Blacks off major league diamonds throughout his career. The boxer was found guilty after the testimony of an alleged prostitute about incidents that occurred before the Mann Act was passed.

Similarly spurious Mann Act charges would later be filed against the likes of the brash Black musician Chuck Berry and alleged communist Charlie Chaplin.

In recent years, use of the statute has aligned closer to its original purpose. The Mann Act helped convict rapper R. Kelly, who used his position in the music industry to seduce and brutalize teenage girls. Ghislaine Maxwell, the abetter of serial abuser Jeffrey Epstein, was also convicted under the statute.

Congress has amended the Mann Act twice to remove the open-ended moral standard that was abused in charging Jack Johnson. And Johnson was even pardoned by Donald Trump in a cynical attempt at wielding this troubled history for political gain.

Despite his posthumous pardon, Johnson’s life unfolded without corrective action. Sentenced to a year in prison, Johnson fled the U.S. to live abroad, fighting boxing matches to support himself for seven years, Finally, having exhausted all resources and fought himself tired, he returned to the U.S. in 1920 to serve his full term in the Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas.

In 1946, Johnson died at age 68 after a car crash. He had hit a telegraph pole in a high-speed collision after angrily driving away from a segregated North Carolina restaurant that refused to serve him — a final jab of injustice to bring down the champ.

But neither the Mann Act nor his prison term could keep Johnson from making his own choices: He was buried in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago next to his white wife.