For nearly 50 years, artist Napoleon Jones-Henderson has brought his vibrant textile works and a potent artistic manifesto to the Roxbury cultural community. Now, the Chicago native’s work is being honored at the ICA Boston in “Napoleon Jones-Henderson: I Am As I Am—A Man,” a three-room retrospective running through July 24.

From the moment viewers step into “I Am As I Am—A Man,” the energy feels different from the traditional white-cube museum model. Brightly colored walls in yellow, green and blue host artworks from the artist’s long and fruitful career. Jones-Henderson was one of the founding members of the artist collective African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA). His work has always centered on exploring and uplifting the Black experience.

Napoleon Jones-Henderson, TCB, 1970. Installation view, Napoleon Jones-Henderson: I Am As I Am—A Man, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2022. Photo by Mel Taing. © Napoleon Jones-Henderson

As a textile and multi-media artist, Jones-Henderson creates intricate and engaging works that have weight and texture to them, creating a dynamic viewing experience. “The warp is simply the canvas,” he says. “The weft are my brushstrokes.”

The exhibition features three rooms. The first shows Jones-Henderson’s work before coming to Boston. The second illustrates how new materials were incorporated into his works here in Boston. And the final room holds three altar-like sculptures dedicated to the spirits of creative individuals connected to Black culture, honoring figures like James Baldwin and Duke Ellington. On March 3, Jones-Henderson will give a talk at the ICA with art historian and curator Dr. Leslie King-Hammond.

Jones-Henderson moved to Roxbury in 1974 for what was supposed to be a temporary one-year teaching post. He never left. Part of the draw to stay in Boston was the rich textile history in New England. Here, he found metallic threads from the 1920s that are wrapped in foil, as opposed to more contemporary threads with a similar but less robust effect. These threads contribute to the “shine” in his works.

Shine is an important characteristic of AfriCOBRA artworks, all of which are meant to draw from meaningful visual aspects of Black culture. “Shine was part of the natural aesthetics of African people. We saw that, looking into our community,” says Jones-Henderson. “A metallic surface reflects light, and as one applies oil to dark skin, it reflects light.”

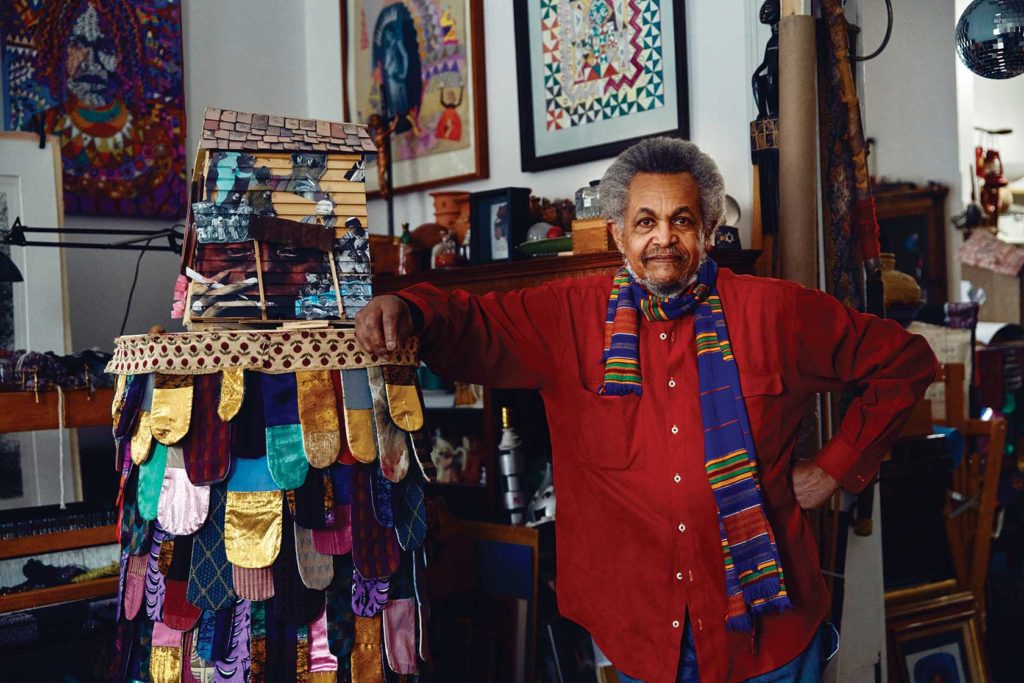

Napoleon Jones-Henderson, Egungun for Duke, 2005. Installation view, Napoleon Jones-Henderson: I Am As I Am—A Man, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2022. Photo by Mel Taing. © Napoleon Jones-Henderson

Music is another intrinsic element for AfriCOBRA and is prevalent in Jones-Henderson’s work. His piece “Blind Boys of Alabama” pays homage to the gospel musical group that turned a stifling experience at the Alabama Institute for the Negro Deaf and Blind in the 1940s into a powerful performance collective. Jones-Henderson’s piece depicts six performers in enamel, copper, gold leaf and wood. He began this piece in 2002, but this show at the ICA is the first time the completed piece has been shown. It includes a row of vintage gloves, commonly worn to church, underneath the figures. Like hands raised in worship, it brings a new vigor to the artwork.

Effective textile tools weren’t the only pull here in Boston. Jones-Henderson has become an integral part of the Roxbury cultural community and has given as much inspiration to the neighborhood as he has received from it. The artist’s home has become a frequent meeting ground for artists. Music plays, food sizzles on plates, and artistic minds from Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan mingle amid Jones-Henderson’s collection of more than 300 original African artworks. He refers to these gatherings as family reunions.

And in “I Am As I Am—A Man,” a member of the family is rightfully recognized and celebrated by Boston’s artistic establishment.

“I know, based on the environment of all the museums in this city historically and present, that this is a very different body of work,” says Jones-Henderson. “I hope viewers take away a sense of an artistic history of AfriCOBRA. I hope they leave here with a sense of spiritual uplift and aesthetic nourishment.”