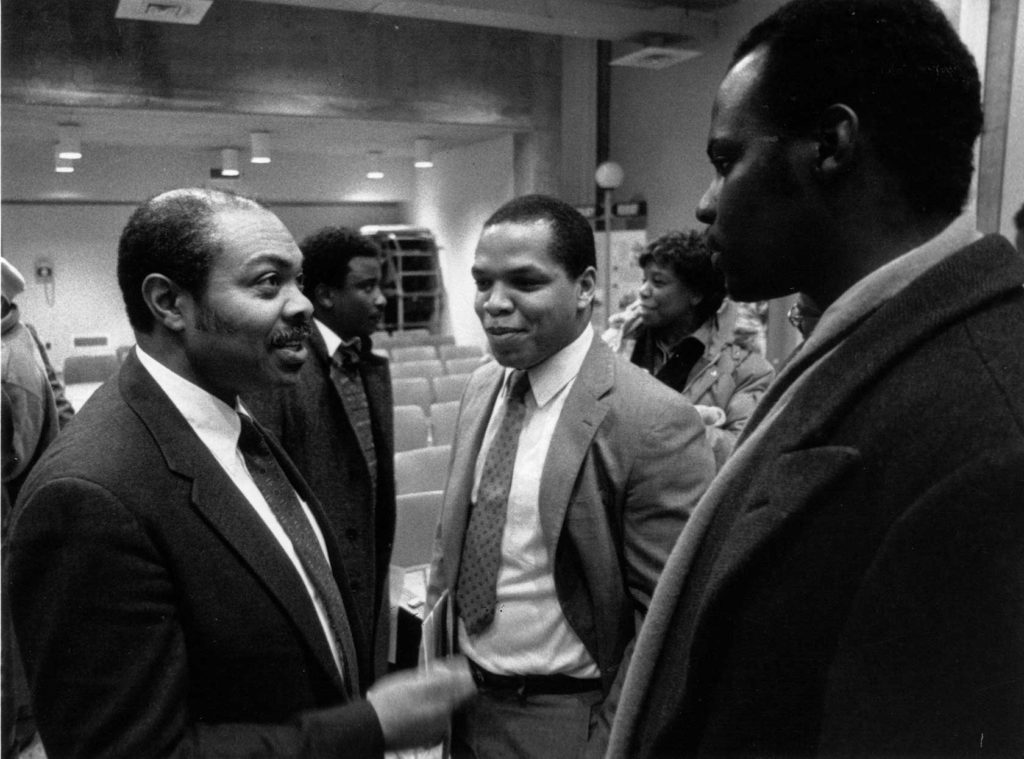

Former state Sen. Bill Owens, 84

Founding member of Black Caucus was ‘transformational leader’

Bill Owens Sr., the first Black state senator elected to the Massachusetts legislature, died Jan. 22 in a Brighton nursing home after suffering a bout with the coronavirus. He was 84.

One of the founders of the Black Legislative Caucus on Beacon Hill in 1972, Owens teamed up with fellow lawmakers to address critical issues like housing, health care and economic development during a turbulent era of protest and progress.

An effective and outspoken organizer, he took a special interest in education during the long and bitter battle over desegregating Boston’s public schools and mounted a successful public challenge to the powerful Senate president to secure funding for a $30 million Roxbury Community College campus.

But the Alabama-born legislator also used his position to tackle national and global issues. He almost single-handedly revived the century-old debate over reparations in America for the descendants of slaves and traveled to Europe, the Caribbean and Africa in service of a Pan-Africanist agenda to connect the Black diaspora to each other and their ancestral homeland.

“He was a transformational leader and kicked down barriers to access opportunities for people who were marginalized,” said his family in a statement. “He made his mark on the world stage from the United States to Europe, Asia and Africa.”

Born near the banks of the Black Warrior River in Demopolis, Ala., in 1937, Owens was raised in the Baptist church by his father, the Rev. Jonathan Owens, and his mother, Mary Alice Clemons Owens, who taught school. The small city, located in the heart of the Black Belt and founded by white refugees of the Haitian slave rebellion, was a Confederate stronghold where segregation and strict control of the Black population continued well into the civil rights era.

Owens came under the influence of the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a local minister who later became a close associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., before his move to Boston at age 15.

Owens attended Boston English High and Boston University, married and opened a dry-cleaning business on Blue Hill Avenue. He later earned a master’s degree in education from Harvard University and studied in a Ph.D. program at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

In his late twenties, an incident occurred that changed his life. Confronted by a racist attack in front of his business, he defended his wife in an altercation and was arrested and sentenced to state prison for assault – a questionable conviction that steeled his determination to confront injustice of any form.

“In 1966, with so much going on in the city over the schools and fights for representation, I couldn’t do much. I was in prison. But I was going to get out and I was going to do my part to change things,” said Owens in a 2017 interview with the Banner.

Upon his release from Walpole in 1967, Owens returned to Mattapan to run his business and join local activists in confronting the systemic bias that denied quality public education to African American students.

Among many battles, he pushed to address appalling conditions at the Gibson School, which was the subject of Jonathan Kozol’s landmark book, “Death at an Early Age,” and led efforts to bring more Black teachers into the classroom, rejecting arguments from the all-white school committee about a shortage of qualified Black candidates.

Owens pushed for reforms to corporal punishment in schools after a white teacher slapped a Black student, knocking her down two flights of stairs. He worked to get a legal case heard in federal court after it died before the state bench and took the issue to the National Education Association during their Washington, D.C., conference.

“We went to the Mayflower Hotel and threatened to disrupt their meeting if they refused to put the issue of ending corporal punishment on their plenary agenda,” he said. “They didn’t want to do it. But they eventually relented.”

In 1972, Owens won a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from Ward 14 and joined four Black lawmakers in launching the Black Legislative Caucus. The idea for the collective effort had emerged from the National Black Agenda Convention held in Gary, Indiana, earlier that year, where 10,000 Black activists from across the country met to plot empowerment strategies. Two years later, after a long fight to create a majority Black senate district, Owens defeated fellow state Rep. Royal L. Bolling Sr., for the seat – the first of five contests between the two men for the post over the next two decades.

While some prominent Black political figures like state Rep. Mel King expressed disappointment with the toggling back and forth between the two – seeing it as undermining political consensus within the caucus – others saw some advantages in the seat rotating between the courtly Bolling and the firebrand Owens.

Former state Rep. Royal L. Bolling Jr., the son of the late senator, said Owens brought a “more direct style in terms of tactics. People like Mel King and Bill Owens were very good on street demonstrations and protests.”

Owens called himself “more radical” than Bolling but recognized that his rival’s style, though less confrontational, could achieve results through other means. “Royal Sr. had been on Beacon Hill a long time, since the early sixties, and had friendships and relationships he didn’t want to violate. I understood and respected that,” said Owens.

The battle to build a new campus for Roxbury Community College, which had moved from a dilapidated Catholic church property on Dudley Street and Blue Hill Avenue to the site of the former Boston State College on Huntington Avenue, proved a high-point of Owens’ career in the Senate.

Though Owens pushed unsuccessfully to have the RCC campus located in the old Boston State Hospital Grounds in Mattapan, he accepted the chosen site on a cleared-out Southwest Corridor parcel at the bottom of Fort Hill in Roxbury and then fought to get it funded.

The House included money for the new complex in its budget but the Senate failed to follow suit. Owens met privately with Senate President William M. Bulger of South Boston but got nowhere.

So he took to the well of the ornate chamber to mount a rare public challenge to the powerful Democrat to put in the money. “I need to know from you today, Mr. President, that the money will be there,” said Owens. “Otherwise, I will not let you run the Senate.”

Owens held up proceedings in the Senate for over three days until the leadership relented.

Though he won that battle, Owens’ frustration with the tightly controlled body and what he viewed as the Democratic Party’s slow walk on issues of racial justice and economic equity resulted in a decision to switch to the Republican Party.

“I told the Democrats to shove it because I wasn’t getting much done and I went to the Republican Party. The Black community had allies there. It was the Republican governor, Frank Sargent, who aligned with us along with white liberals and Republicans in the legislature to sustain vetoes of unacceptable redistricting plans for the Black senate seat,” he said.

“The House and the Senate were mostly controlled by a lot of Irish people who were not interested in creating a Black district. Some of the reps from outlying areas, like Ed Markey, were willing to take a risk to back us but people like him were few and far between.”

Ousted by Bolling in 1982 after his switch, Owens would rejoin the Democratic Party and return one more time to the Senate in 1988 – defeating Bolling in their final clash — before losing the seat to attorney Dianne Wilkerson in 1992.

By the time of Owens’ last electoral bid, the Bolling-Owens rivalry had become an extended family affair as Boston School Committee member Shirley Owens-Hicks defeated Royal Jr. for his Dorchester/Mattapan seat.

During his years in office, among many other legislative highlights, Owens helped create the State Office of Minority Business Assistance and the passage of a state assault weapons ban.

In his final term, he seized upon the issue of reparations. The idea had been first proposed during the Reconstruction era by the ardent abolitionist U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and revived by Black Power advocates in the sixties. In the late 1980s, reading about a $1.2 billion federal measure offering reparations to Japanese-American victims of internment in World War II, Owens filed a bill to create a study commission to consider how to provide equitable compensation to the descendants of those whose free and forced labor built America.

Owens attracted a national spotlight to the issue, which has gained renewed momentum as part of a broad racial reckoning in the wake of protests sparked by the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

U.S. Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, a leading member of the Congressional Black Caucus, contacted Owens and filed a bill modeled on the Massachusetts measure to create a federal reparations study commission.

Owens, drawing on his global contacts cultivated over two decades as a Pan-Africanist, travelled to Africa and Europe to build international support for the idea.

“Bill Owens was always an avid student of history and interested in connecting the disparate Black communities around the world,” said Carlotta Scott, an Owens friend who served as chief of staff to the late U.S. Rep. Ron Dellums of California. “We took a delegation to Grenada after the revolution there and worked on issues in Nigeria and Zaire. When the issue of reparations came up, Bill came to Washington to meet with the Black Caucus and educate us about the idea.”

While Owens’ national and global interests were used against him in his final losing Senate campaign, Black Caucus colleagues like former state Rep. Byron Rushing said he was raising legitimate issues and following a long historical tradition. “Bill decided early on he was not going to be a Pan-Africanist in theory – we had all read the stuff – he was going to be one in reality. He was going to go look at it. And live it.”

More locally, his interest in Black communities around the globe was reflected in his work with the diverse Caribbean and African populations in his district.

Shirley Shillingford, founder of the popular Caribbean American Carnival in Boston, said Owens helped sustain and support the celebration of island culture. “Bill was an ambassador for all,” she said.

Former Sen. Wilkerson – a rumored candidate for her old seat in the wake of Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz’s bid for governor this year – said she always admired the way Owens fiercely defended the Black community whenever and wherever it was threatened. No matter what anyone else thought.

“Bill Owens was a Black activist, a Black nationalist before that had a name,” said Wilkerson. “He was an up-north civil rights activist at a time Boston wasn’t ready.”

“He was not afraid to say what needed to be said,” commented the Rev. Miniard Culpepper, who is also reportedly mulling a run for Owens’ old seat. “He was a mentor to me and a good friend. Some people criticized him for his focus on reparations but he really believed it was something to strive for because of the blood, sweat and tears that Black people put into the building of this country. He said you can’t heal until you make up for the sins of the past.’

“For 50 years, Bill Owens was my friend and inspiration,” said U.S. Sen. Ed Markey of his former State House colleague. “His presence grounded me in the realities of today’s struggles and his spirit lifted my gaze and countless others to the opportunities and justice that remained to be created for future generations.”

“What motivated Bill Owens above all was stopping what he saw as injustice, no matter what anyone thought,” said Rushing.

“If he felt that Black people were being treated badly, there was nothing else to do but stand up and name it.”

Owens is survived by three daughters, Sharra Owens-Schwartz, Laurel and Brenda Owens; three sons, Curtis, Bill Jr., and Adam; two sisters, Shirley Owens-Hicks and Roberta Owens-Jones; 12 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.