In the past week, Boston Public Schools teachers and staff have seen their highest-ever number of COVID-19 infections — with 1,202 staff out on Monday — and a post-winter holiday return to school marred by shipments of ineffective face masks and expired at-home tests courtesy of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

The surge in cases has wreaked havoc on the state’s school systems, with a staggering 89,000 students and 20,000 staff testing positive for the coronavirus statewide from the opening of school in September through the first week in January, with more than half that number occurring before the omicron variant took hold here.

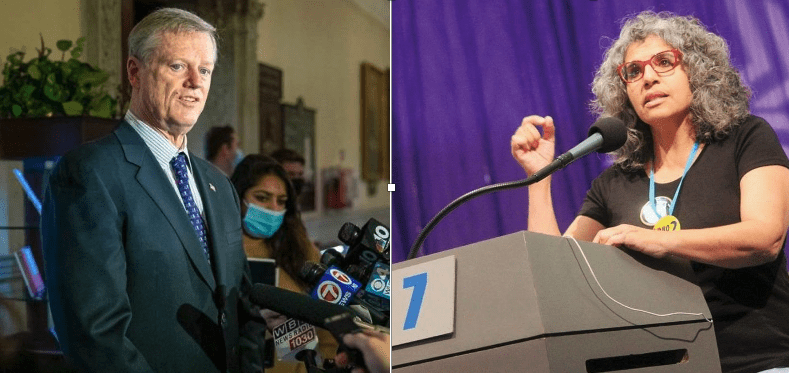

While teachers unions and district leaders have sought temporary closures of schools that have been hampered by staffing shortages caused by outbreaks, state education Commissioner Jeffrey Riley and Gov. Charlie Baker have stood firm in DESE’s policy barring schools from closing for more than four days.

“The rules here are pretty simple,” Baker told reporters last week during an appearance in Salem. “We count in-person school as school. If the school districts are not open at some point over the course of the year, they can use snow days until they run out of snow days. But they do need to provide their kids with 180 days of in-person education this year.”

Monday, Baker doubled down on his stance.

“We’ve said all along that we think the best place for kids is in school,” he told reporters at the State House.

The Baker administration’s policies underscore vast differences in their approach to the COVID pandemic and those of local municipal officials — a chasm that has seemingly grown wider with the rapid spread of the omicron variant. Baker and Riley’s unwillingness to budge on in-class instruction and seeming inability to procure and distribute adequate masks and tests put the administration at odds both with the unions and with local officials.

Massachusetts Teachers Association President Merrie Najimy in a statement last week, “Since the start of the pandemic, Governor Baker and Commissioner Riley have demonstrated gross incompetence in their failure to take vital steps to keep students, educators and communities safe.”

Speaking to the Banner, Najimy said her union wants in-school instruction, but that schools should have the option to close temporarily when infections reach a critical point. The ban on remote learning makes in-school instruction worse in schools experiencing COVID outbreaks and the resulting shortages of teachers and other staff, she said.

“Classes get canceled,” she said. “You have kids in study halls. There’s no meaningful learning if you don’t have proper staffing.”

Like Najimy, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu says her aim is to keep schools open through mitigation strategies, but during a press conference Monday, she acknowledged that staffing shortages are placing a strain on the system and said schools may have to resort to remote learning, regardless of Riley’s order.

“Whether or not we get credit from the state for a day of remote learning, if a school needs to do that because of staffing issues, we are going to do that if that’s the safest way to administer learning that day,” she told reporters. “It just means that we would have to make up days at the end of the year.”

If Boston schools close, it won’t be the first clash between Boston officials and DESE. BPS closed the Curley School in November following a pre-omicron outbreak among students and staff there. The 10-day closure led to a detente between Riley and BPS Superintendent Brenda Cassellius, with the former insisting the damage to learning and student well-being inflicted by remote learning outweighed the risks of COVID transmission in the building.

State Rep. Nika Elugardo, who represents the Curley school in her Jamaica Plain-based district, said she raised concerns with Riley, but to no avail.

“He thought the school should be coming to him and asking him what to do,” she said. “I think it should be the other way around. “When teachers, parents and students all feel like DESE isn’t responding to them, that’s a problem.”

McCormack Middle School teacher Neema Avashia wrote an op-ed on WBUR’s Congnoscenti blog, calling on state leaders to apologize after state officials distributed faulty masks and expired tests and then initially blamed local districts for the fiasco.

A spokeswoman for Riley issued a letter last week acknowledging that some of the masks distributed were non-medical grade, but insisted that, if worn properly, they would be effective. The letter also emphasized that under DESE policy, mask wearing is optional.

“The use of the KN95 masks is voluntary, and staff should be aware that their choice of masks is ultimately a personal decision,” the letter reads.” Teachers and staff should wear the masks according to their comfort level.”

The commissioner has not acknowledged that many of the at-home tests distributed were expired.

Najimy says Riley’s silence on the issues underscores the danger students and teachers face in Massachusetts.

“The commissioner’s cavalier attitude after he made such a dramatic mistake is what puts us in jeopardy,” she said.

State Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz said the state’s lack of response is indicative of a lax approach to the pandemic.

“The Baker administration and DESE have left educators, parents and local leaders to pick up the pieces with their disorganized, lackadaisical response to the omicron surge,” she said in a statement sent to the Banner. “Instead of planning ahead to address predictable challenges over the last two weeks, the state waited until the crisis was already on us before starting to execute a response.”

Speaking to reporters Monday, Wu said the city may choose to create its own in-school testing program. Because the state requires that families opt in to its testing program, many students whose parents have not done so are not being tested. Wu said the city may follow the lead of other districts that have created their own programs that require parents who don’t want their children tested to opt out.

“We’re looking at what that might mean,” she told reporters.