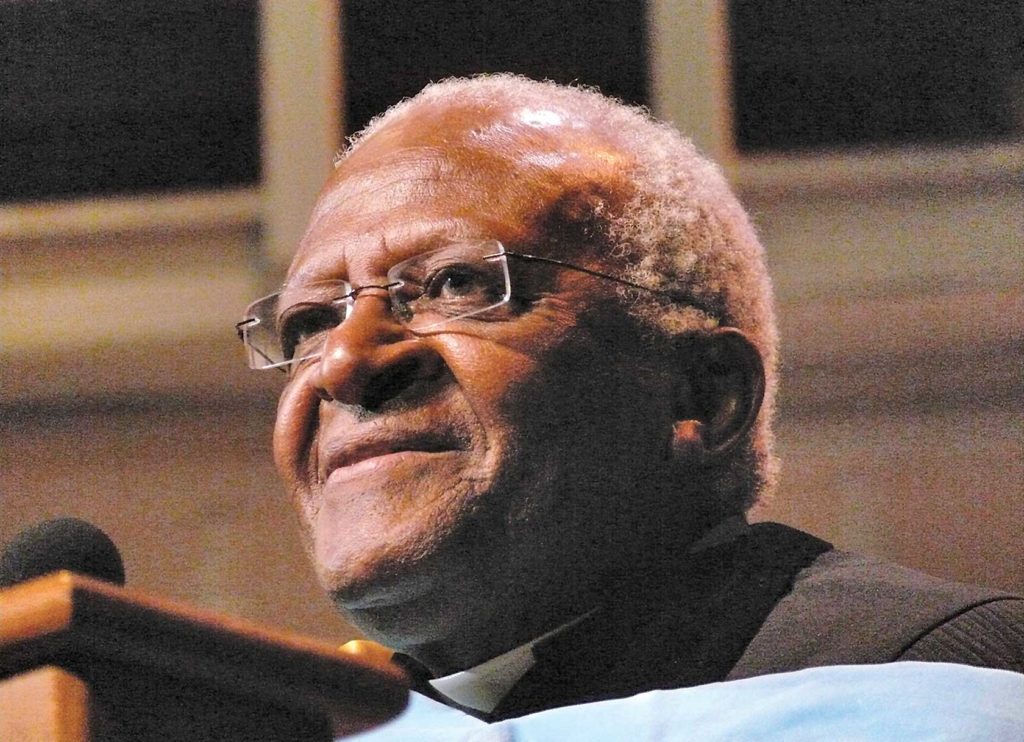

South African cleric Desmond Tutu, 90

Anglican archbishop served as moral voice of anti-apartheid fight

Desmond Mpilo Tutu, the charismatic South African cleric who lent a powerful voice and presence to the battle against apartheid, died of cancer on Sunday at age 90.

The death of the former Anglican archbishop came on St. Stephen’s Day in the church calendar, the day when Christians mark the martyrdom of a first-century Jerusalem deacon known, like Tutu, for his service to the poor and the powerless.

Born into poverty, the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize winner rose to become one of the world’s most-recognized preachers and activists, using his position as head of the Anglican communion in South Africa and chair of the South African Council of Churches to bear witness against racial segregation in the former British colony.

But “the Arch,” as he liked to be called, was also known for his numerous small acts of kindness and love, taking time to shower attention on drivers and bellmen and busboys and waitresses wherever he travelled, embracing humans and humanity in every form.

Wearing an oversize pectoral cross, a clerical collar and bishop’s purple, Tutu was physically diminutive and morally imposing. His sermons and speeches, delivered in modulating, mellifluous pitches with song, stories, humor and passion, drew on the Gospels and the everyday experiences of the people he championed to help bring down the architecture of apartheid.

Tutu’s unanimous election as Archbishop of Cape Town in 1985 was a first for a Black man in the church and came at a critical time in the global struggle against the brutal system of racial separation. His investiture, attended by Coretta Scott King, Harry Belafonte, Stevie Wonder and U.S. Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, attracted worldwide notice.

While embraced by white liberals, Tutu drew criticism from Black radicals unhappy with his commitment to nonviolent social change. That stance came as little comfort to the South African government as Tutu’s testimony at home and abroad helped set in motion both the release of African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela in 1990 and Nelson’s 1994 election as president of the first post-apartheid government.

“You have already lost! Let us say to you nicely: You have already lost!” said Tutu in a widely quoted 1988 address to the government. “We are inviting you to come and join the winning side! Your cause is unjust. You are defending what is fundamentally indefensible, because it is evil. It is evil without question. It is immoral. It is immoral without question. It is unchristian. Therefore, you will bite the dust! And you will bite the dust comprehensively.”

After apartheid’s fall, Tutu took up the difficult challenge of heading the nation’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a model effort to bring accountability and healing through the wrenching process of owning up to moral and legal failings.

“Some poked fun at the sessions, calling them ‘the Handkerchief Commission,’ deriding the Arch for weeping — which he did openly,” wrote Eleanor Dunfey-Freiburger, a longtime Tutu friend who attended the hearings and whose family-run Global Citizens Circle hosted the bishop at numerous discussion events.

“How did he respond?” she wrote. “He pleaded with those present and all who were listening ‘to listen to every single story: They are all the same and they are all unique … In those hearings, I saw the very worst that humans are capable of and I saw the very best of what we humans are capable of.’”

After his mandatory retirement as archbishop after a decade in office, Tutu continued to serve as a moral conscience in his home country and abroad. He spoke up for the rights of Palestinians and became one of the governing African National Congress’s sternest critics, accusing the party of corruption and selling out the promise of Black rule for self-enrichment. He called for the resignation of President Jacob Zuma and vowed not to vote again for the ANC to head the beloved country he dubbed “The Rainbow Nation.”

He also traveled widely, frequently visiting New England for events large and small, including appearances at weddings and baptisms and talks at churches and conferences.

Tutu adopted the cause of gay rights as well, opposing the Anglican’s church stand against accepting gay priests. The issue became publicly personal when his daughter Mpho Tutu, one of his four children, was forced to leave the priesthood after marrying a woman in 2015.

“If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn’t worship that God,” he told the BBC in 2007, according to the New York Times.

More recently, Tutu called the ravages of climate change “the human rights challenge of our time.”

While he adored gatherings of friends and family, the human rights icon found it difficult to fully set aside the demands of a man considered the world’s pastor. During a rare getaway at the secluded New Hampshire home of Jerry Dunfey and Nadine Hack, Tutu fielded a call from CNN about Israeli-Palestinian relations.

“So within an hour, our sleepy dead-end road was filled with media trucks,” said Dunfey. “They broadcast the interview live split screen with Vanessa Redgrave from London and the Arch from Waterville Valley. Then he went back to happily playing with his grandchildren.”

Among the many tributes to Tutu, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, an ally of the bishop’s in the anti-apartheid struggle, called him “a patriot without equal; a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead.”

“The big baobab tree has fallen,” said the African National Congress. “South Africa and the mass democratic movement has lost a tower of moral conscience and an epitome of wisdom.”

“The world has lost one of its brightest lights and most joyous spirits,” said Colette Philipps, the Boston activist and publicist who worked with the Tutu family to raise money for his foundation. “He was a champion for human rights and social justice who used his platform for good.”

Tutu was born in 1931 in what is now the North West province of South Africa, in a family of mixed Xhosa and Motswana heritage. His father taught at a local Methodist school and his mother was a domestic worker. After his family moved to Johannesburg, Tutu contracted tuberculosis and came close to death. One of his frequent visitors was the Rev. Trevor Huddleston, a white Anglican priest and prominent anti-apartheid campaigner.

Tutu attended the University of South Africa and began his career as a teacher. In 1955, he married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, to whom he gave unfailing credit for supporting and guiding him through decades of bitter opposition to injustice. Deciding to enter the ministry, he was ordained in 1960 and two years later moved to London to study theology at King’s College.

Returning to South Africa, he held a series of teaching and administrative posts until being appointed Bishop of Lesotho, a landlocked kingdom encircled by South Africa. He used his appointment in 1978 as general-secretary of the South African Council of Churches to build a consensus case against white rule.

His ascension to the archbishopric of Cape Town cemented his role as the country’s leading religious voice against apartheid.

During the years of railing against economic, political and social repression, Tutu demonstrated physical as well as moral courage. In one notable incident, he plunged into the midst of an angry township mob to rescue an accused police informant from certain death.

Following Tutu’s death on Dec. 26, South Africa declared a week of national mourning and announced plans for a Jan. 1 funeral service at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, where mourners have placed flowers beneath the church bells pealing in honor of the late archbishop.