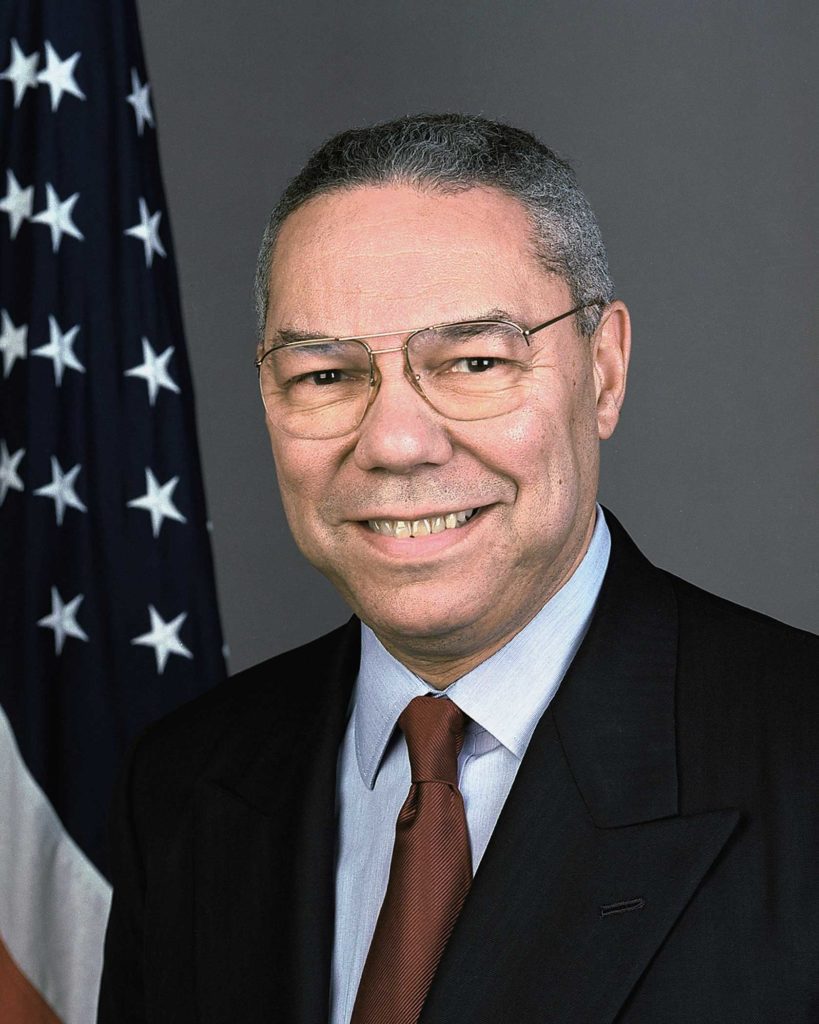

Colin Powell, the Harlem-born son of Jamaican immigrants who rose to the heights of U.S. military and civilian power, died Oct. 18 at age 84 of complications related to COVID-19.

Powell grew up in a working-class family in the Hunts Point section of the South Bronx, his father a shipping-room foreman in the garment district and his mother a seamstress. He was an indifferent high school student before attending City College in New York on a Reserve Officers Training Corps scholarship and avidly taking to the discipline of drill-team training with the Pershing Rifles.

Powell’s meteoric career arc began as a U.S. Army officer after college. Encountering segregated public facilities in the late 1950s on trips to military garrisons in the South, Powell brushed aside the ignominies of Jim Crow and excelled as a young officer, leading to battlefield command in Vietnam and decorations for leadership and bravery after he suffered injuries pulling soldiers out of a burning helicopter.

Tall, square-shouldered and charismatic, he advanced swiftly through elite Army assignments until his skills attracted the attention of civilian leaders. Toward the end of the Cold War, President Ronald Reagan named him the first Black national security adviser, and, in the succeeding administration of President George H.W. Bush, the four-star general became the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In that role, he oversaw the invasion of Panama in 1989 and the capture of presidential drug lord Manuel Noriega, as well as the triumph of the first Gulf War in 1991. Under Powell, U.S. forces swiftly chased Saddam Hussein’s army of occupation out of Kuwait. Powell famously advised the president not to pursue Saddam to the gates of Baghdad, citing what became known as the “Pottery Barn” rule of war — if you break it, you own it.

Powell’s worries about the disaster potential of American forces ruling over a deeply divided Middle East country — with Shia and Sunni antagonists turning their combined venom on U.S. occupiers — proved prophetic.

Powell retired from the military in 1993, published a 1995 best-selling memoir, “My American Journey,” and briefly flirted with a run for president in 1996, fueled by his status as the nation’s most popular public figure.

Five years later, newly elected President George W. Bush made Powell the nation’s first Black secretary of state. His tenure in government service ended less than two years after testifying before the United National Security Council about Saddam Hussein possessing weapons of mass destruction. That testimony led to the invasion of Iraq and marked the only prominent sour note in Powell’s long career.

The secretary of state’s detailed evidence, based on flawed and misleading intelligence, provided cover for many reluctant elected officials to get behind the Bush administration’s push for war in Iraq. The conflict ended up diverting resources and attention from the campaign against the Taliban in Afghanistan and unleashing unforeseen whirlwinds of political and military chaos in the Middle East.

The retired soldier and diplomat rued that appearance and the lethal impact it had on U.S. soldiers and Iraqi civilians, not to mention the whole Mideast, for the rest of his life.

Though a Republican, Powell endorsed Barack Obama for president in 2008 and backed Joe Biden against Donald Trump in 2016. He never shied away from making tough political choices, which he considered part of the job of both civilian and military leaders.

“We are a political nation,” he told the New York Times in 2007. “It is not a dirty word.”

Throughout his four decades in public service, Powell was noted for not only leading by example, but also for encouraging the ambitions of young African Americans.

He could bring a roomful of journalists to their feet, as he did in a 1989 speech to the National Association of Black Journalists in New York, with broadcast and print scribes alike applauding and seeking his autograph.

In a 2012 visit to Northeastern University in Boston to deliver the commencement address, he unexpectedly appeared at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute. Running into the director on the stairs, Powell said, “Someone told me this is where the brothers hang out,” and was ushered into a private meeting with Black graduates preparing to receive their diplomas.

Ralph Cooper, an Air Force veteran who was the former director of the Roxbury-based Veterans Benefits Clearinghouse and a founding director of the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, remembered Powell as a general and diplomat who sought out the view of those working behind the scenes, the invisible corps.

“The thing that really impressed me is that no matter what office he held — four-star general, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, secretary of state — he listened to the people. He was known to seek out the counsel of those without great power, just to listen and learn,” said Cooper from his home in Houston.

Marydith Tuitt, commander of the William E. Carter American Legion Post #16 in Mattapan, called Powell a “trailblazer.”

“He did so much for African American service members and veterans,” said Tuitt, who enlisted in the Navy and served as a jet mechanic aboard three aircraft carriers. “He was always an awesome role model for all of us to emulate.”

In addition to his college studies, Powell earned an MBA at George Washington University in 1971 and won a prestigious White House fellowship the following year, serving under future defense secretaries Caspar Weinberger and Frank Carlucci. His military assignments included commanding an infantry battalion in North Korea; stints at the Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and at the Army War College; a brigade command with the 101st Airborne Division; and command of the Fifth Corps in Germany as a three-star general.

Powell is survived by his wife Alma, whom he married in 1962 after meeting on a blind date; three children, Linda Powell, Anne Powell Lyons and Michael Powell, who served as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission; and four grandchildren.

Toward the end of his life, suffering from cancer but before being felled by COVID, Powell was asked by journalist Bob Woodward who was the greatest man, woman or person he had ever known.

“It’s Alma Powell,” the aging statesman immediately replied.

“She was with me the whole time,” Powell told him. “We’ve been married 58 years. And she put up with a lot. She took care of the kids when I was, you know, running around. And she was always there for me, and she’d tell me, ‘That’s not a good idea.’ She was usually right.”