Terence Blanchard’s ‘Fire Shut Up in My Bones’ opera to air Wednesday, Oct. 27

Unfolding with primal power, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” the opera by multi-Grammy Award winning jazz trumpeter and composer Terence Blanchard, seizes the audience from the start and never lets go.

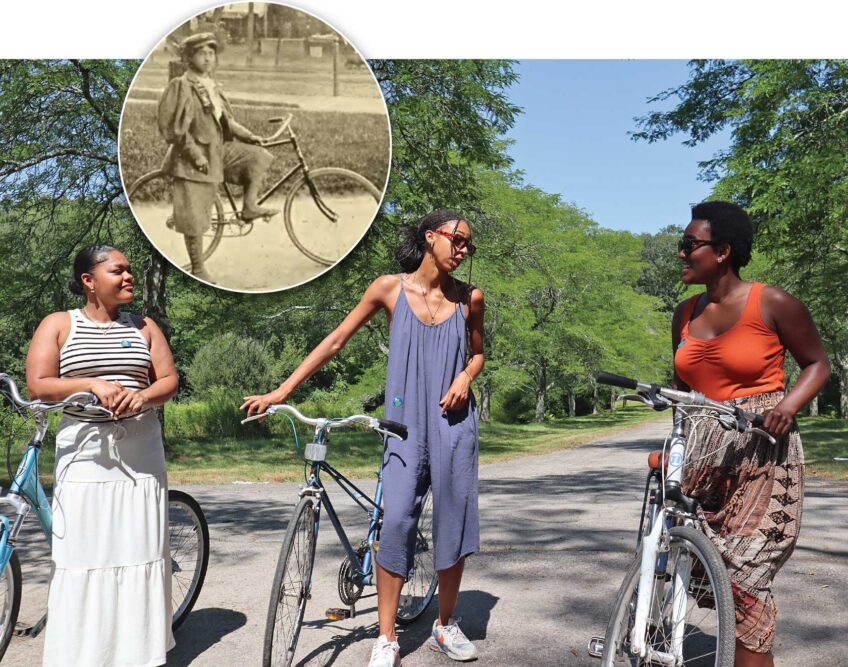

Will Liverman as Charles in a scene from of Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” PHOTO: Ken Howard/Met Opera

This production of the Metropolitan Opera, its first after an 18-month pandemic shutdown, concludes on Wednesday, Oct. 27 with a live simulcast showing at six Greater Boston cinemas. Encore screenings include one on November 20 at Shalin Liu Performance Center in Rockport. In March, the Lyric Opera of Chicago will present the opera on stage.

While the thrill of live performance is incomparable, the Met simulcast directed by Gary Halvorson has several advantages. The audience is immersed in sound, and views shift from panoramas of haunting sets and kaleidoscopic crowd scenes to the faces of performers, who, together with the libretto, the music, and the staging, give this production its astonishing naturalness and immediacy.

New Orleans-born Blanchard and libretto author Kasi Lemmons infuse the opera with an African American language of loss, resilience and redemption.

Will Liverman as Charles and Angel Blue as Greta in Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” PHOTO: Ken Howard/Met Opera

First presented in 2019 by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, the opera is based on the 2014 memoir by Charles M. Blow, a columnist for “The New York Times.” His account spans his childhood in rural Louisiana, where at age 7 he was sexually abused by an older cousin, and a young adulthood haunted by this trauma. As he writes, “I had to resort to the most useful and dangerous lesson a damaged child ever learns — how to lie to himself.”

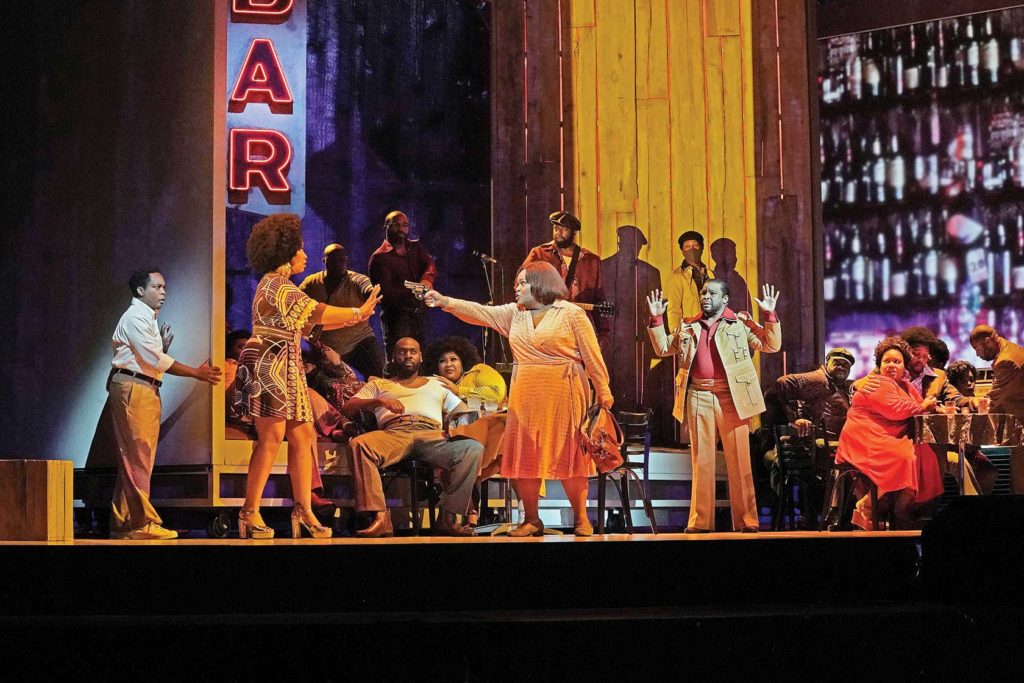

The Met’s staging, like the music, conjures the inner life of Charles. Deft lighting, projections and minimalist sets sketch such scenes as abandoned shacks, a barroom, and a road at night in a narrative that is an extended flashback. The story begins and concludes as the adult Charles, poignantly portrayed by baritone Will Liverman, returns to his mother’s house wielding a gun, ready to kill his visiting cousin.

Making palpable his inner world, Charles is joined by his 7-year-old self, nicknamed Char’es-Baby. Performed with unaffected dignity by Walter Russell III, 13, the boy counters other forces shaping Charles: Destiny and Loneliness. Each is personified by soprano Angel Blue, who injects these roles with seductive appeal. Blue also plays Greta, a woman Charles yearns for. Matching a soaring soprano with earthy warmth, Latonia Moore is the family’s fiercely loving matriarch, Billie.

Walter Russell III as Char’es-Baby and Will Liverman as Charles in Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” PHOTO: Ken Howard / Met Opera

Blanchard, who has composed scores for Spike Lee’s films, tells stories with music. Describing “Fire” as “an opera in jazz,” he combines sweeping orchestral passages with syncopated filigrees that punctuate intimate moments. (Jeff “Tain” Watts, percussionist here for Met conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin, in November will perform at the Boston world premier of “Iphigenia,” the new opera by Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding).

Co-directed by James Robinson and Camille A. Brown, also its choreographer, the opera leavens introspection with spectacle — such as a high-octane step dance by the fraternity Charles joins at his college. Humor, too, makes its way in. A tender child, Char’es-Baby is teased by his rough-and-tumble siblings. As grown men, they still talk big but let their momma do their laundry. Charles will do his own.

Lemmons blends poetry and everyday naturalism in her libretto, which is laced with evocative refrains. Billie and Charles tell others, and finally, one another: “You know, love with a laugh only goes so far. Sometime I just want it straight, plain and somber, fragile and naked.”

Repeating a phrase voiced throughout the opera, in the concluding scene Char’es-Baby tells gun-wielding Charles, “Sometimes … You gotta just leave it all behind … and leave it, just leave it, in the road!”