Population changes upend voting patterns

Gentrification, displacement lead to lower turnout, tilt toward progressives

The traffic circle in front of the Holy Name church in West Roxbury has a revered status in Boston politics. Four precincts in the high-voter turnout Ward 20 cast ballots in the parish hall on Election Day, and the circle at the intersection of Centre Street and West Roxbury Parkway has become a pilgrimage site for electoral candidates running citywide.

Last month, a little more than a week before the Sept. 14 preliminary election, the circle was split between campaign volunteers holding signs for at-large city councilors Annissa Essaibi George and Michelle Wu, both of whom would advance to the Nov. 2 final in the mayoral election.

Their campaigns have come to symbolize the clash between Boston’s old and newer politics, with Essaibi George’s moderate platform resonating in the more conservative, predominantly white precincts in South Boston, Dorchester’s Neponset neighborhood and West Roxbury while Wu’s progressive platform is finding appeal in liberal precincts in Jamaica Plain, Roslindale and the South End.

In past election cycles, Boston’s predominantly Irish and Italian-American neighborhoods have dominated local politics, but in this year’s race, changing demographics in South Boston, Dorchester and other traditionally high-turnout, white working-class enclaves could spell an end to those areas’ dominance.

At the West Roxbury traffic circle back in September, Wu’s campaign appeared to break the mold of the old politics. Among those backing Wu, with her pro-rent control and police reform agenda, were a Boston police officer and retired fire department employee Frank Sullivan, a longtime West Roxbury political activist.

“It is historic when you think about the impact of this race and what it means,” Sullivan said, wearing a Michelle Wu T-shirt and holding an eight-foot-tall purple sign with the name “Wu” in white lettering. “People across the city do realize the historical significance of this moment.”

While many Black Bostonians have expressed disappointment that a Black candidate did not advance to the general election, this year’s election has already broken several significant electoral molds: Two Black candidates together received 40% of the vote; Wu, an Asian American, received a third of the vote; and the top four vote-getters were women.

The historic finish occurred just eight years after the last open mayoral election saw two white men — then state Rep. Martin Walsh and at-large Councilor John Connolly — emerge victorious from a racially- and gender-diverse field of candidates. The result seemed to reaffirm the stubbornness of the longstanding white-dominated political order.

Shifting demographics, early victories

Back in the year 2000, when U.S. Census results revealed for the first time that the city’s demographics had shifted to a majority of people of color, political activists harbored expectations of change. For decades, Black candidates had sought to break through the electoral stranglehold the city’s Irish American and Italian American politicians seemed to have, fielding candidates for at-large seats on the city council and school committee (when it was elected), with few successes.

Mel King’s 1983 run for mayor, in which the former state representative became the first Black man to advance beyond the preliminary, provided a stark reminder of the then-unassailable advantage white candidates had in a city that for decades had voted along race lines. His coalition of Blacks, Latinos, Asians and liberal whites, which he called the Rainbow Coalition, garnered barely more than a third of the city’s vote, delivering Raymond Flynn of South Boston a near two-to-one victory.

But in the early aughts, candidates of color began racking up victories in citywide contests with Felix D. Arroyo becoming the first Latino to win a citywide city council seat in 2003 and Sam Yoon in 2005 becoming the first Asian American councilor elected citywide.

While those early victories raised hopes among political activists of color, the 2013 mayoral election — the first race for an open mayoral seat in more than 20 years — seemed to reaffirm the longstanding dominance of white candidates, with Walsh and Connolly besting a diverse field that included Black and Puerto Rican candidates. In a city that was becoming increasingly diverse in both ethnicity and political orientation, predominantly white, conservative-leaning neighborhoods and the candidates who hailed from them still seemed in control of the city’s political sphere.

Recent change

So what’s changed over the last eight years?

Candidates of color, many who have graduated from training programs aimed at increasing diversity in state politics, continued to run for office, and those candidates began to rack up impressive wins. In the 2011 at-large city council race, Ayanna Pressley became the top vote-getter, the first time a person of color earned that distinction. In 2017, that distinction went to Michelle Wu, who became the first Asian American to dominate the at-large vote.

In 2018, a year of upset victories, Pressley unseated 20-year incumbent U.S. Rep. Michael Capuano, and political newcomer Rachael Rollins topped a field of candidates for Suffolk County District Attorney that included a white former prosecutor, Greg Henning, who many presumed would win, along with two other women candidates and two other Black candidates.

By the time the 2021 election cycle had started, the changed political dynamics were apparent to all: No prominent white male politician had stepped forward to run in the mayoral race. In the West Roxbury/Jamaica Plain-based District 6, longtime incumbent Matt O’Malley bowed out of the race, leaving the council — a body once dominated by Irish American men and women — with just two Irish American men, at-large Councilor Michael Flaherty of South Boston and District 3 Councilor Frank Baker of Dorchester’s Savin Hill neighborhood.

Influx of young professionals

Sheriff Steve Tompkins, who in addition to running his own campaigns for reelection has also volunteered on campaigns of prominent Democrats such as U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Ayanna Pressley, says the changes in the city’s electoral map have a lot to do with the 58,000 residents the city has gained in the last 10 years.

“A lot of these folk are younger,” he said. “A lot of them haven’t grown up here. You have a different demographic that is not as involved in the voting process.”

Neighborhoods such as the South End and Back Bay with higher-income, white professionals have long lagged behind the city average in voter turnout, a factor Tompkins and others ascribe to the transient nature of tech and finance workers, many of whom change cities when they change jobs.

Census data show that while the city has become more diverse, with Blacks, Latinos and Asians claiming a greater share, long-term Boston residents, at 43% of the population, are in the minority. Because much of the increase in the city’s growing diversity is driven by immigrants from Asian, Central American and Caribbean countries, many of these new residents are not citizens and not yet eligible to vote.

The population shift, some of it fueled by gentrification of Boston’s neighborhoods, has meant that the city’s electorate has undergone profound changes. White Bostonians have not been immune to these changes. Traditional strongholds of Irish American and Italian American voters have undergone rapid displacement that has led to lower voter turnout and decreased political power for white politicians.

In South Boston, Precinct 1 in Ward 6 provides a window into these changes. The precinct includes the entirety of the Seaport District, an area that 20 years ago contained 1,747 active voters. As gleaming glass and steel apartment towers went up in the Seaport District and industrial buildings were converted to lofts and condos in the adjacent areas in the neighborhood, the precinct gained more than 5,000 registered voters, many drawn to the city’s growing life sciences and tech sectors. Yet turnout for municipal elections in the Seaport, which has become one of the city’s most populous precincts, has been dismally low, with just 16.8% casting ballots during this year’s preliminary, far below the citywide average of 25%.

Young professional newcomers haven’t confined themselves to the Seaport. They’ve penetrated South Boston and Dorchester along the Red Line, taking up residence in the newly constructed buildings and condo-converted triple-deckers, former school buildings and churches throughout the neighborhoods.

In South Boston, their influence on lower voter turnout was readily apparent during the 2018 Democratic primary that propelled Pressley and Rollins into office. That election marked the first time in recent memory that South Boston’s Wards 6 and 7 posted lower turnout percentages than Roxbury’s Ward 12, underscoring the political ramifications of the exodus of working-class reliable voters from the neighborhood.

Ward 6 Democratic Committee Chairman Bob O’Shea, a lifelong South Boston resident, has witnessed the changing political dynamics in his neighborhood in recent years. As a Little League coach, he’s watched as young professionals began setting down roots in South Boston while many long-term residents have moved to more affordable communities such as Scituate and Weymouth. Now he coaches the children of the new professionals on his little league team.

“They’re all college-educated,” he said of the neighborhood’s newcomers. “They lean more progressive than the city kids I grew up with.”

In this year’s preliminary, 42% of O’Shea’s Precinct 1 neighbors backed Wu, with just 22% backing Essaibi George, the favored candidate in virtually every other South Boston precinct.

As for the declining share of the vote, O’Shea says South Boston is not alone.

“It’s a pattern we’re seeing citywide,” he says. “What’s happening to us is also happening to the Black community.”

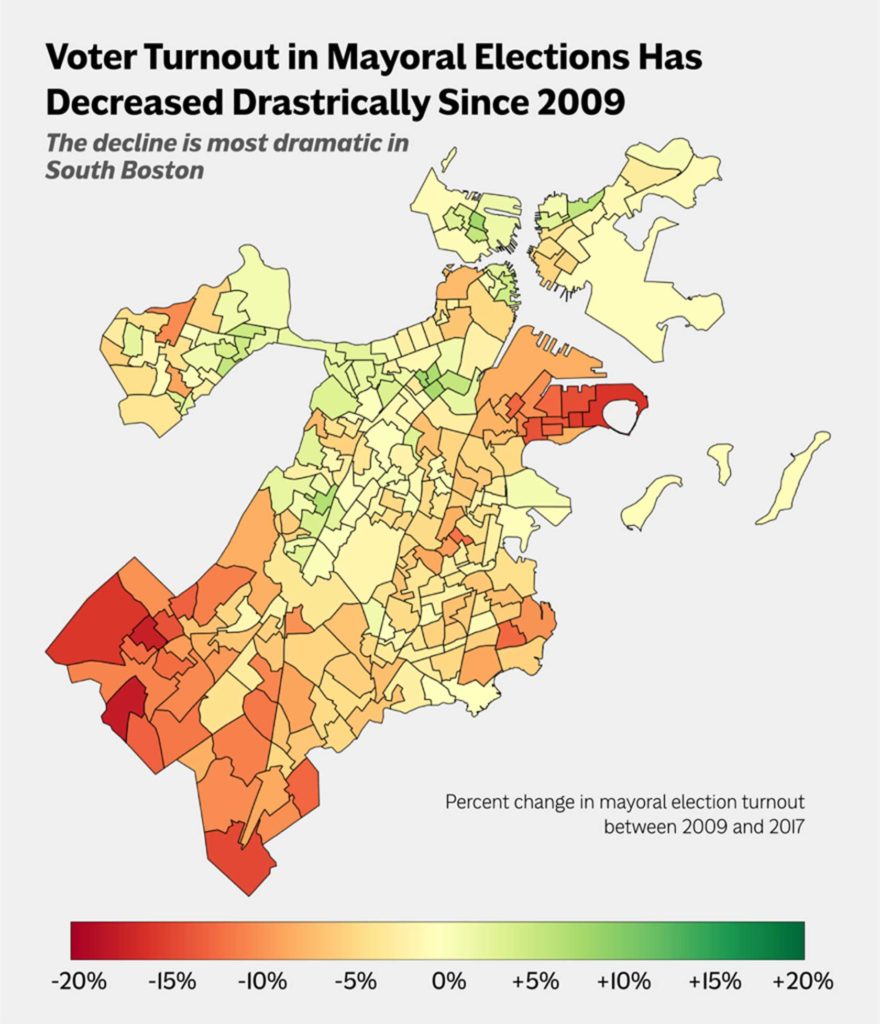

According to an analysis of voting patterns undertaken by Boston University’s Spark! lab, South Boston was among the neighborhoods that saw the greatest drop in voter turnout between the 2009 and 2017 municipal elections. Other neighborhoods that saw drops include West Roxbury, Neponset, and the Readville and Fairmount sections of Hyde Park — neighborhoods that in the last 30 years have traditionally been the power base for Irish American politicians.

A rise in progressive voters

Political activists in the Black and Latino communities have described the traditionally high-voting communities on the city’s periphery as the “donut.” Now, as those communities have seen their voter turnout wane, the more progressive-voting white communities in downtown neighborhoods, the South End, Jamaica Plain and Roslindale have increased their turnout.

Together with more heavily Black, Latino and Asian precincts in Chinatown, Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan and Hyde Park, those communities have made manifest Mel King’s Rainbow Coalition in recent years, helping deliver candidates of color like Michelle Wu commanding leads in at-large races and helping propel Ayanna Pressley into Congress.

While the number of African Americans in Boston dropped by 9,800 between the 2010 and 2020 Census counts, the decline in voter participation in predominantly Black neighborhoods in Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan has not been as dramatic as those in traditionally white working-class areas.

At the same time, voter turnout has increased markedly in neighborhoods with growing populations of upwardly mobile whites, including the South End, Chinatown, Charlestown, East Boston and the Pondside section of Jamaica Plain, which is part of Ward 19, along with Moss Hill and Forest Hills.

That ward, in the 2018 primary, the year Pressley won her Congressional seat, saw the greatest turnout in the city, with 40% of registered voters casting ballots — a result Jamaica Plain Progressives co-chair Ed Burley attributes in part to his group’s voter engagement strategies.

“J.P. Progressives has worked at this for more than a decade,” he said. “The work and the synergy with having the right organization and the right neighborhood came together to activate folks who would normally be indifferent.”

Burley, an attorney who grew up in a Jamaica Plain home his parents bought for $15,000 in 1970, has watched Jamaica Plain turn whiter and more affluent in recent years.

“There’s much more money here,” he said. “All the houses are remodeled. It’s turned into this perfect-looking neighborhood.”

He says that the 2016 election of Donald Trump and the post-George Floyd resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement helped persuade his well-heeled, politically uninvolved Jamaica Plain neighbors to become more active in elections. J.P. Progressives sends questionnaires to candidates, holds candidate forums and posts information about candidates’ positions on its website.

Volunteers from the group also hand out lists of their endorsed candidates on Election Day and in the weeks leading up to then.

“People are grateful to have an independent group who has vetted candidates for them,” Burley said. “A lot of people want to make the right choice but won’t get information on candidates on their own.”

Data collection and analysis for this story was provided by students from Boston University’s Justice Media Computational Journalism co-Lab, a collaboration between the Faculty of Computing & Data Sciences’ SPARK! Program, the College of Communications, and the BU HUB. Participating students were Ethan Singer, Jake Neenan, Yagev Levi, Anqi Lin, Abdullah Albijadi, Thachathum Amornkasemwong, Audrey McMillion, Gordon Ng, Sarthak Dawark, Tania Hasanpoor, and Ji Zhang with assistance from co-Lab Advisors Gowtham Ashokan and Osama Al-Shaykh.