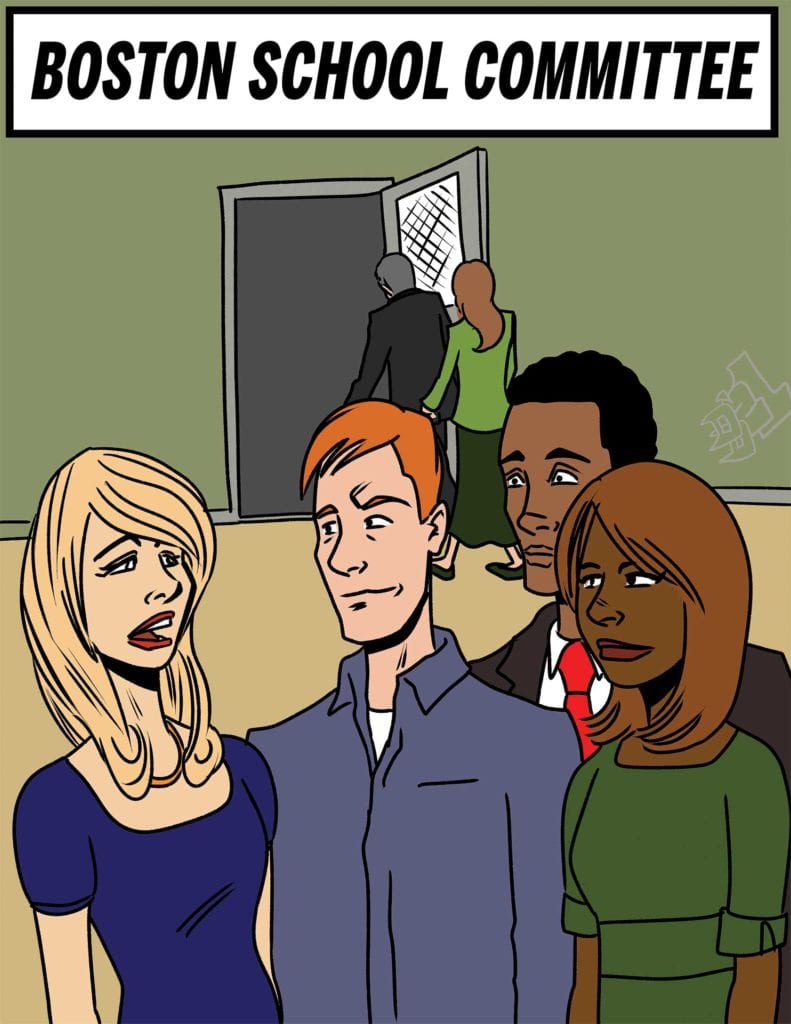

Strong supporters of democracy hope that citizens will instinctively back the wisest course of action if it is well publicized and properly presented. However, the success of Donald Trump has raised serious questions about the reliability of the political strength of sound ideas. A recent poll showing public support for the return of elected school committees in Boston causes great concern among those who remember the 1970s.

Louise Day Hicks and Pixie Palladino generated considerable racial hostility in Boston with their unrelenting campaign to discriminate against Black students. Their bigotry caused Boston to lose millions of dollars in federal funds for education. The disrespect of the school committee for the federal district court judge presiding in the Morgan v. Hennigan case forced the judge, W. Arthur Garrity, to impose bussing as the only remedy that allowed reasonable federal oversight. That solution was not warmly embraced.

School committee obstinacy also resulted in another public school change that might have been more carefully considered. Girls complained that it was more difficult to be admitted to Girls’ Latin School than were boys to Boston Latin School. Girls needed higher scores in the admission test than was required of boys. This was clearly discriminatory and was therefore unconstitutional.

Brilliant girls had outgrown their building in Codman Square, Dorchester. Judge Garrity’s proposed solution was to find a larger building. Defiantly, the school committee refused. Judge Garrity’s response was simple. As of September 1972, the historical Boston Latin School became coeducational. Students were to be selected on the basis of their academic qualifications without regard to gender.

Once again, Judge Garrity was pilloried, this time for destroying the century-old tradition of Boston Latin School being exclusively for boys. However, another possible solution to the problem was embarrassingly simple. The formal name for Girls’ Latin School was Boston Latin Academy; that school was established in 1877 primarily for girls. Everyone called it Girls’ Latin.

In past years, there was a common practice in Boston to establish high schools in various sections of the city. Roxbury Memorial High School was built on the corner of Warren and Townsend Streets in 1926. After operating for 34 years, the school closed and the building was left vacant.

Roxbury Memorial had been created as a dual school: a boys’ side and a girls’ side. Each had its own principal and administrative officers. It was inevitable that this would become the new site of the Boston Latin Academy. The old location of Girls’ Latin would then join the list of closed schools in Jamaica Plain and elsewhere that have been converted to housing.

BLS was established as the first public school in the nation. There was no preparatory school. In fact, BLS was founded, among other objectives, to prepare students for Harvard College. The demanding academic curriculum of BLS has forced many students to transfer to another school before graduation.

A more imaginative approach would have been to move Girls’ Latin to the Boston Latin Academy building that used to house Roxbury Memorial High School. A coed Latin School could be established in another classroom area. In this way, both Girls’ Latin and BLS could retain their historic identities.

Any Girls’ Latin alumna will assert that their education was equivalent to, or even better than, that offered by BLS. The only problem was that qualified applicants were rejected. The elected school committee found a way to make a problem worse.