Boston’s other underground railroad

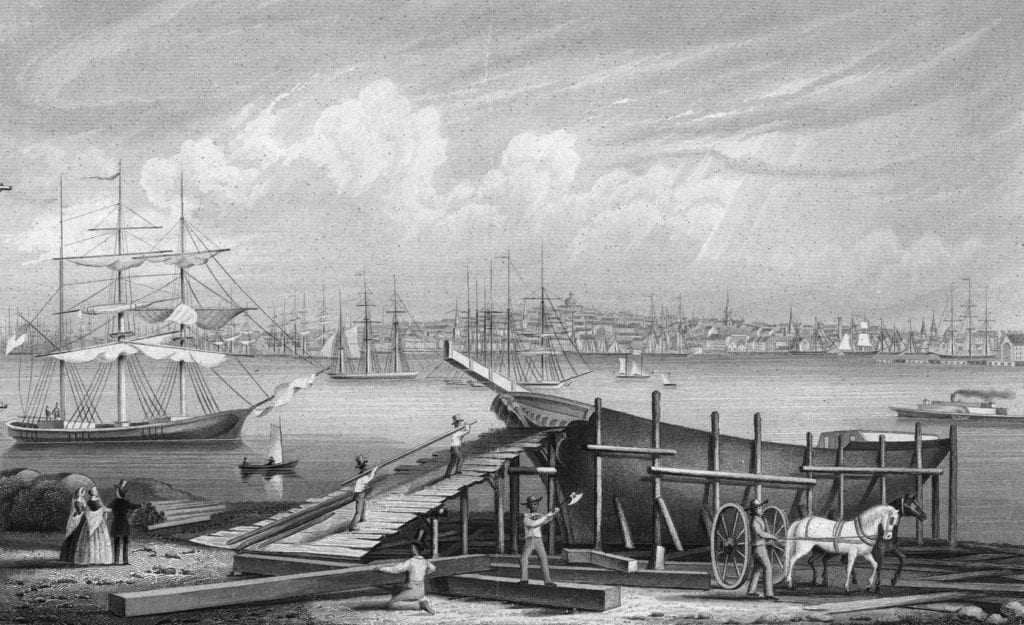

City’s maritime culture provided access to ships heading north

Boston has always been at the forefront of American history. Nevertheless, residents may know little about the city’s link to the underground railroad, a life-saving network of safe houses established by slaves before the Civil War.

As Black History Month kicked off, Boston Public Library partnered with the National Park Service to commemorate freedom-seekers and stowaways that traveled here to escape enslavement.

“[There was] that strong free Black community that lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill before the Civil War, a community that only made up about one-and-a-half percent of Boston’s entire population, but was crucial to leading a social revolution,” said historian Shawn Quigley during a Feb. 2 Zoom lecture. Quigley has spent years working with the Boston African American National Historic Site on Beacon Hill.

Most of the Black individuals that lived in that area opened their doors to freedom-seekers who fled enslavement in the South, said Quigley. This Black-led social revolution helped enslaved men and women find refuge in northern cities or in Canada, where U.S. Marshals could not chase them.

“[As] part of the compromise of 1850,” Quigley said, “the Fugitive Slave Law allowed for United States Marshals to go into any northern state or territory, such as Boston, and arrest individuals suspected of being fugitives from enslavement.” U.S. Marshals also could jail any civilian that refused to cooperate with the search for escaped slaves. Those who housed fugitives spent six months in prison or faced a fine equivalent to $33,000 today.

Freedom-seekers were able to use ports such as Boston’s to sneak from boat to land and back. Quigley said that it was almost an everyday occurrence for slaves to take passage aboard a ship to go north to Boston and beyond.

Many African Americans worked on both the ships and the docks, said Quigley. Some were free, some were not. The “maritime culture,” said Quigley, created a space for informants to pass messages to and from the ports.

“This provided an opportunity for individuals who were enslaved in these port cities to make connections, learn when a ship [was] coming and, if lucky, get on board that ship and make their way north,” said Quigley.

He noted that the conditions on the boats were cramped, dangerous and “extremely uncomfortable.” Most hiding spots had little sunlight, as travelers wanted to stay undetected.

Enslavers would go to extreme lengths to prevent slaves from escaping. They thought of the freedom-seekers as their property and wanted to keep them enslaved.

“There are often reports of captains boarding ships, searching the vessels and in some instances, actually smoking these vessels out with tobacco and sulfur to try and literally make these individuals come up for air,” said Quigley. “This is a horrendous system. It’s horrific.”

Enslaved people were often subjected to brutal torture while on board northbound boats. Other abolitionists, including ship captains who aided fugitives, were also punished. Quigley mentioned Jonathan Walker, a Massachusetts resident who came to be known as “the man with the branded hand.” Walker was an abolitionist punished in 1844 for helping seven slaves escape. He was tried and convicted of stealing slaves, forced to pay a $600 fine and received a branded “SS” on his hand for “slave stealer.”

“This is what people were up against,” said Quigley. “This is what people were willing to risk, to help [slaves] gain freedom.”

Many enslaved people lost their lives en route to Boston. Those that survived often endured dangerous trials before landing on shore. Quigley recalled Phillip Smith, a stowaway who fled slavery in North Carolina. After being discovered on board, Smith ripped off a ship plank and leapt overboard. He swam through freezing waters and ended up frostbitten on a nearby island, where he was able to hail a passing ship. Smith made it to Boston, where he found a “strong network of abolitionists.” Others were not so lucky.

Those who escaped had to start a new life somewhere unknown. “I can’t even imagine the bravery, but also the agonizing decision-making that that would take,” said Quigley. He quoted Frederick Douglass from the abolitionist’s 1855 memoir: “No man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape,” Douglass wrote. “All that he has is at stake; and even that which he has not, is at stake also. The life which he has may be lost and the liberty which he seeks, may not be gained.”

Quigley expressed appreciation for those that made the underground railroad possible: “The determination and agency of the individuals escaping enslavement… the boldness of those in the mainland that are willing to help freedom-seekers.” Bostonians supported these freedom-seekers by forming a coalition called the Boston Vigilance Committee, which provided a financial backbone for the underground railroad.

Women were among those saved by the maritime underground railroad. At only 15, abolitionist Elizabeth Blakeley escaped slavery after leaving Wilmington, North Carolina on a boat bound for Boston. When enslavers discovered she had escaped, they tried smoking out the vessel “three times with tobacco and sulfur to get Blakeley to reveal herself,” said Quigley.

Blakeley did not give up. She arrived in Boston in the winter of 1849. “It took nearly four weeks for her to arrive in the city, cold and frostbitten,” said Quigley. “She survived. And later, but a month after she arrived in the city, she went on stage at Faneuil Hall at the Massachusetts anti-slavery society’s annual meeting.”

Blakeley is just one of thousands that made their way through Boston’s underground railroad. “These stories are powerful, daring, inspiring,” said Quigley. “Despite the incredible danger and low odds of success, Elizabeth Blakeley and others risked everything to seize their freedom.”