Rafer Johnson, the world decathlon champion who carried the Stars and Stripes at the opening of the 1960 Rome Olympics and became a lifelong Kennedy family friend and Special Olympics ambassador, died at age 86 on Dec. 2 at his home in Los Angeles.

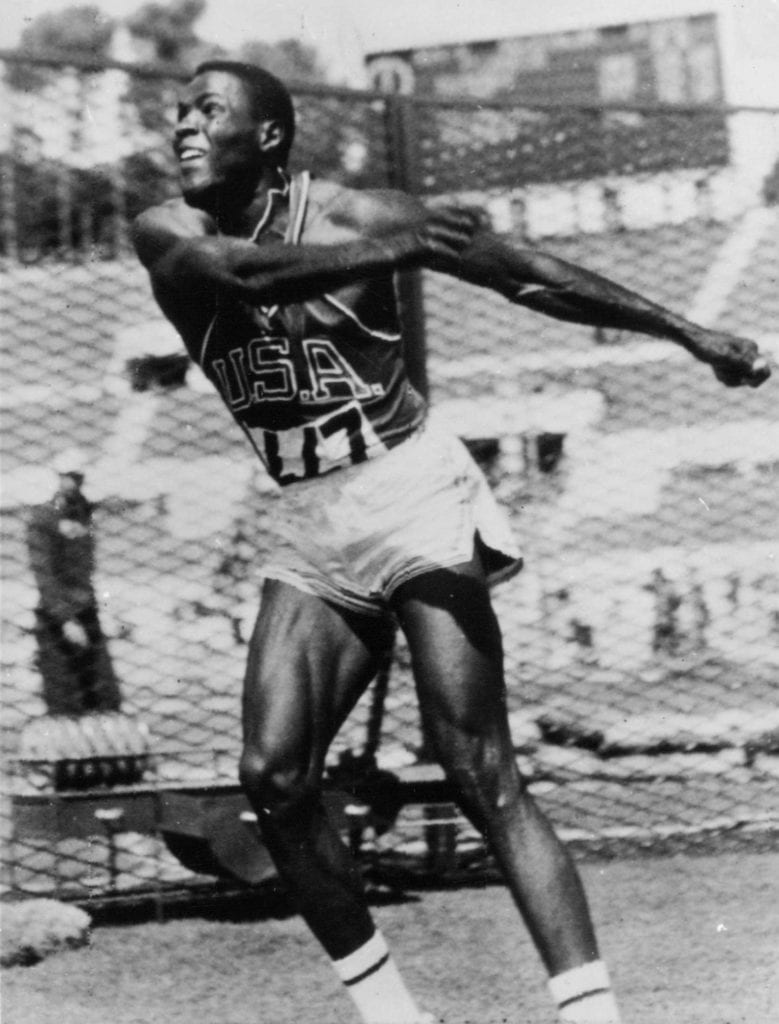

Johnson rose from poverty to become the first Black captain of the U.S. Olympic team, set world records in the grueling 10-event decathlon competition event and win a thrilling victory at the 1960 games, which took place during a time of global attention on racial challenges in America.

Like Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin games, Johnson and fellow gold medalists Cassius Clay and Wilma Rudolph were viewed not just as athletes but as symbols of racial progress in a troubled time of continuing resistance to integration in schools, at lunch counters and on public transportation.

The handsome athlete, 6-foot-3 with a chiseled physique and ramrod posture, met U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy after the Rome games and established an instant friendship. He became a frequent visitor to Kennedy’s Hickory Hill estate in suburban Washington and a godfather to his son Max and campaigned for Kennedy in his 1964 Senate and 1968 White House races.

Along with L.A. Rams lineman Rosey Grier, Johnson traveled with Kennedy throughout California in the lead-up to the presidential primary, guiding him through testy meetings with Black Panthers who challenged Kennedy’s commitment to racial justice. He was walking just behind the senator in the pantry of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles on the night of Kennedy’s Democratic primary victory in the Golden State when shots from a .22-caliber handgun rang out, striking Kennedy multiple times from behind. Johnson pried the firearm from the grip of Sirhan B. Sirhan and wrestled him to the floor.

Later that year, Johnson heeded the call of Special Olympics founder Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the senator’s sister, launching the group’s Southern California chapter and eventually serving as its chairman.

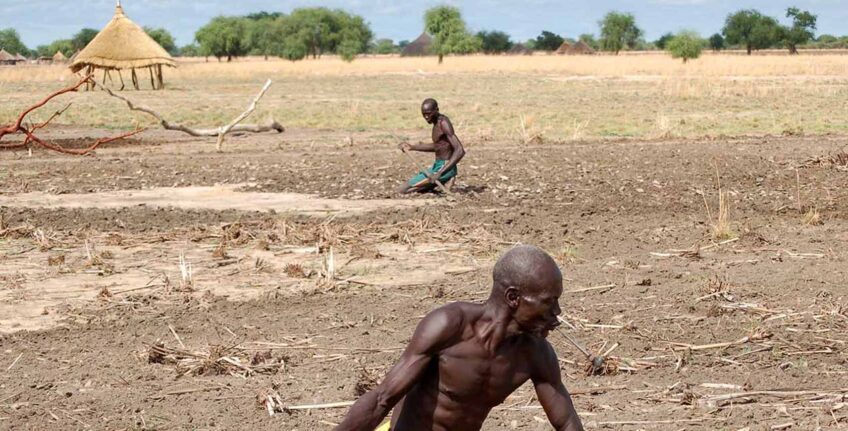

Born in Texas during the Great Depression, Johnson lived briefly in Dallas before his family followed the migration of many African American families to California, leaving segregation and dead-end job prospects behind. But the West Coast hardly turned out to be the land of milk and honey, more like the “Do Re Mi” of the Woody Guthrie song than the Shangri-La of movie reels.

The Johnson family took shelter in a railroad boxcar in the San Joaquin Valley while his father worked in a nearby cannery, scraping together money to rent a home.

A stellar athlete at Kingsburg High School, he declined a football scholarship to focus on track at UCLA, where he also played a season for the legendary John Wooden on the basketball team. As a freshman competing in only his fourth decathlon, Johnson won the 1955 Pan-American Games in Mexico City and took the silver medal at the Melbourne Olympics the following year.

At the Rome games, Johnson ran neck-and-neck with his UCLA teammate, Taiwanese athlete Yang Chuan-Kwang, and was leading going into the final event, the 1,500-meter race, needing only a close finish to clinch the gold.

“I planned to stick with him like a buddy in combat,” Johnson said in a 1990 interview in the Los Angeles Times. “I had one other advantage, and I don’t think C.K. knew this at the time. This was my last decathlon. I was prepared to run as fast as I had to in this last race of my life.”

He finished 1.2 seconds behind his friend – with over eight seconds to spare to win the gold and retire as the world’s greatest athlete.

After his Olympic triumph, Johnson toured the country as an inspirational speaker, landed movie parts and began a career in broadcasting. During a 2008 forum at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston, held on the 40th anniversary of Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 White House campaign, Johnson said his commitment to his friend’s race came with a price.

“I had just gotten the best job I could imagine in my life – as a sports commentator on KNBC in Los Angeles. It was a tough choice,” said Johnson, who set aside his career ambitions to join the whirlwind campaign that started in the Senate Caucus Room in March and ended in the Ambassador Hotel 11 weeks later.

Toward the closing days of the primary, Kennedy ignored the advice of aides worried about urban riots in the wake of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder weeks earlier and accepted an invitation to meet with Black Panthers in Oakland.

“They were very rough on the senator,” said Johnson at the JFK Library. “And, as usual, he said the same thing to that audience that he had said to any other – that in spite of frustrations, respect for law and order had to prevail.”

Kennedy got shouted down as a patsy of uncaring white society. Future California Assembly Speaker and San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, then a back-bencher in Sacramento, tried to calm down the audience and got called a “technicolor nigger,” and Johnson was denounced as an Uncle Tom.

“It got very heated,” said Johnson, “and at the end they were quizzing me about why I would serve a white man, and I told them that it was because Robert Kennedy would serve them to the very best of his ability.”

With Johnson surrounded by questioners, Kennedy left the church to drive to San Francisco.

“They were halfway over the bridge before they realized I was left behind,” said Johnson.

According to aide John Seigenthaler, Kennedy “turned around and asked Rafer a question, but he wasn’t there to answer. ‘Rafer? Rafer?’ he said. When we got back, Rafer was out in front of the church, talking with a group of children. It was very moving.”

The next morning at a rally in West Oakland, an activist called Black Jesus who had been among the hardest on Kennedy and Johnson circulated in the crowd, telling the crowd to treat Kennedy with respect. Johnson watched, amazed, at the end of the rally when some of the Black Panthers who had shouted Kennedy down the night before “were walking beside his car to protect him because of all the people reaching up and grabbing him and not letting go.”

On June 5, 1968, the night of the primary, Johnson was walking just a few paces behind Kennedy when Sirhan fired the fatal shots.

“My hand clamped down on the weapon,” wrote Johnson in “The Best That I Can Be,” his 1998 autobiography. “Rosey’s hand came down on mine. With a dozen others pushing and shoving, we forced Sirhan onto a steam table, then to the floor. I twisted Sirhan’s fingers to free up the weapon.”

The campaign over, Johnson was soon working to build the Special Olympics into the largest global service organization for children with mental and physical disabilities.

He memorably carried the torch in the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles and lit the cauldron at the top of a flight of 99 stairs to mark the start of the games.

Johnson is survived by his wife, Elizabeth, two children and four grandchildren.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Breathe-Life-4-ToGetHe_WM-150x150.jpg)