Renowned civil rights leader Malcolm X (1925-1965) has inspired films, an opera and books, including the 1965 autobiography he wrote with “Roots” author Alex Haley. Yet, he remains an enigma, an iconic figure whose life continues to yield new narrative threads.

The latest work to mine fresh ground in the life of Malcolm X is “Detroit Red,” a play by award-winning actor, lyricist and hip-hop playwright Will Power on stage through Feb. 16 in a world premier production at the Emerson Paramount Center in Boston. Presented by ArtsEmerson, “Detroit Red” focuses on the formative years of the young man who would become Malcolm X, who from age 14 through 21 lived mainly in Roxbury, where a reddish tint to his hair earned him the nickname “Detroit Red.”

Directed by Lee Sunday Evans, the 90-minute, intermission-free production unfolds as a series of 10 episodes, beginning soon after 14-year-old Malcolm Little arrives from Michigan to live with a half-cousin, Ella, following the breakup of his family. With his father dead and his mother institutionalized after a breakdown, he and his six siblings have been sent into foster care.

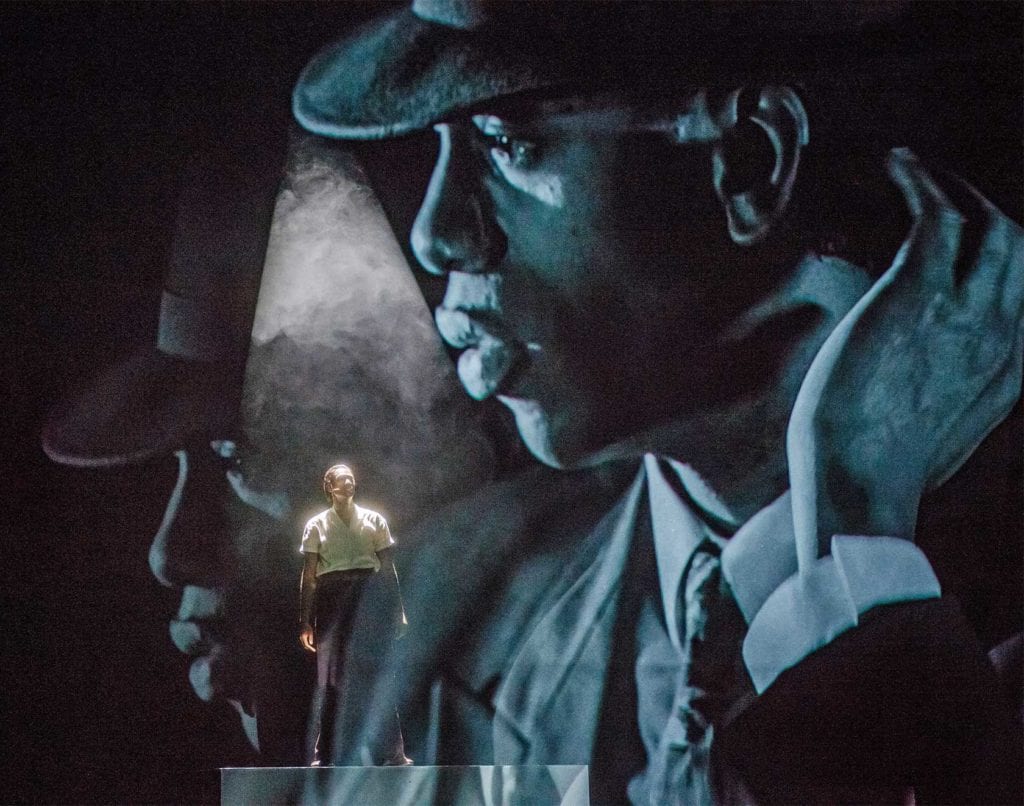

The production employs inventive, multimedia staging that complements Power’s rich, rhymed dialogues. Stage-size photographic projections visualize turbulent, decisive moments as the young Malcolm finds his way. Behind these larger-than-life images, the actor performing as Detroit Red is visible on the stage, a small figure dancing in exaltation or writhing in pain — the human behind the epic, wrestling with his inner and outer life.

Adam Rigg designed the spare and effective sets as well as an array of costumes for Malcolm and the play’s 12 characters, from debonair suits and plain togs to butler jackets and cocktail dresses.

The production opens and concludes with a grainy, newsreel-style video of Malcolm at age 21. Gun in hand, he confronts a detective in a Boston jewelry store who is about to arrest him. Malcolm has come to pick up a stolen watch he had left for repair, and now faces prison — or worse. Following the brief news clip is the voiceover of Power’s second-by-second description of the act of pulling a trigger. The play concludes by returning to the scene, as the young Malcolm resolves his dilemma — to shoot or not — with a split-second, life-changing decision.

The ensuing episodes cast the young Malcolm in situations of escalating debasement and risk.

Most of the episodes are trio pieces, with actress Brontë England-Nelson playing the six white characters. Sophia is a glamorous party girl with ready access to her husband’s cash and hatred for her class, who helps Red and his friend and sidekick Shorty get jobs posing as butlers and burglarize the households of her wealthy neighbors. She also plays three male train passengers who antagonize Malcolm as he hawks sandwiches, one of his many jobs in the course of the play. And she enacts a pampered Brahmin whose desired services from Red extend beyond his role as butler. Tackling the male characters matter-of-factly, not imitating male voicings or physical tics and instead relying on costumes, England-Nelson lets them remain types, which serves the play, in which they are just that.

Partnering with Red in low-risk crimes as well as coaching, protecting and befriending the young man are six black characters, played with warmth, humor and worldly wisdom by Edwin Lee Gibson. A pleasure to watch, he performs each role with the relaxed ease of a natural.

The interactions between Gibson and the handsome and taut Eric Berryman, who plays Detroit Red, benefit from the palpable chemistry between the two men — particularly in the occasional comic moments, when Red lets down his guard.

Berryman’s young Malcolm is mercurial, eager to please in each new job so he can help his cousin Ella keep her house. But as he encounters abuse from his white patrons, he vents his rage, until later when it takes physical form, through tempests of gorgeous language, evoking the family and home life he has lost with a lyrical litany of foods or remembering his revered Baptist minister father with the mesmerizing oratory of the black church.

Bringing a bit of levity to the play’s tense showdowns are its moments of humor and friendship between the young Red and his middle-aged mentor, Shorty.

In one scene, Shorty, a sax player, teases the newly arrived teenager for hair like “weeds,” and persuades him to become “a hep cat” with a new hairdo that involves a scalp-scorching lye potion. The process is a kind of ablution, inducting him into his new world. Shorty tells Red, “You about to be baptized in the waters of cool homeboy!”

In another scene, Malcolm and his friend, an aspiring comic, spend the night on a rooftop. Malcolm tries to catch some sleep, but his friend keeps him awake with jokes and words of wisdom. In this veiled tribute to a real-life friend of Malcolm X, John Elroy Sanford, who became the actor and stand-up comedian Redd Foxx, Sanford encourages his friend by saying, “Even if we are two homeless dishwashers/The sky is ours too, Red.”

His mind on bigger money, Red soon decides to “feel bad but look good” and heads to New York City, until his employer, Lucia, orders the young man back to Roxbury for his own good.

Ending where it begins, “Detroit Red” returns to the newsreel. Now age 21, Malcolm has learned a thing or two, and sizes up the situation: With one gesture, he can become a cop killer, ending two lives, the detective’s and his own.