Artist Anthony Young explores generational trauma in AREA Gallery show

The brushstrokes of Anthony Young’s paintings are laced with generational trauma. In his show “Passage: A Space Between Too Much and Never Enough,” running at Boston’s AREA Gallery through Feb. 2, Young explores with delicacy and dynamism the roots of this trauma and the ways to overcome it.

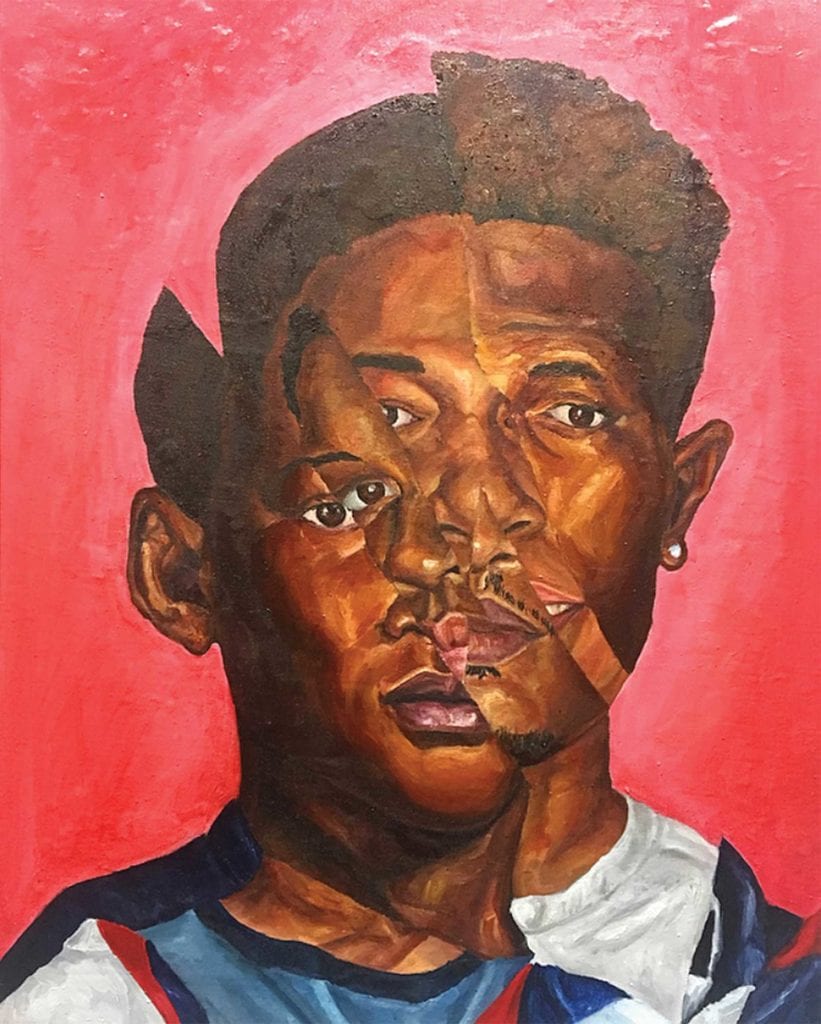

A cast of oft-forgotten characters greets viewers at the gallery entrance. Young’s composite portraits fuse the faces of racial violence victims into one. In “They Have Names III,” the eyes of Emmett Till, Mike Brown, Sean Bell, Jon Ferrell, Rumain Brisbon and Terence Crutcher stare out at the viewer from a canvas carved in blacks and browns. The piece at once pays homage to these lost lives, brings their names back into the conversation and illustrates how each individual moment of violence leaves its mark on the collective black experience.

In his artist statement, Young paraphrases a quote from Ta-Nehisi Coates, “Being violent could cost me my body but so could not being violent enough,” he writes. “I pose the question of how we might move forward, conquer our fears and thrive, all while addressing historical and contemporary issues in our society and communities.”

In the oil painting “Candlelight Vigil” we see what on first glance looks like two boys walking along the esplanade at night. But on further inspection it is not two boys, but one boy split into half-a-dozen pieces. A contemporary face stares ahead, moving forward, while a caricatured face stares at the viewer with a single tear dropping from its one-dimensional eye. At the boy’s feet, Nike sneakers go in one direction while bare feet go in another. This boy, and every black body, is carrying these histories, these caricatures and these conceptions with him everywhere.

Many of the paintings in the show are mirrored in pencil-on-paper sketches that lend ghostlike eeriness to the monochromatic pieces. Young’s statement says, “These works incorporate symbolic materials such as bleach and gunpowder to challenge common notions about the black body that are branded into the black psyche, and explore the power of cultural imprinting.”

Young’s works illustrate the generations of trauma and oppression that black bodies carry inside them on a daily basis. But they also point toward hope of healing. The boy in “Candlelight Vigil” is weighed down, but he’s not stopping, he’s determinedly pressing forward. The faces of memorialized victims refused to be normalized and refuse to be forgotten. At each turn of his pencil and stroke of his brush, Anthony Young reveals another layer of the black American experience and another moment of strength.