“When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art” is the poetic title of a powerful new show at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston.

The exhibition borrows its title from a line in the poem “Home,” by Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, which states, “You only leave home/When home won’t let you stay.”

Yinka Shonibare CBE, The American Library (detail), 2018. Hardback books, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, gold foil. Installation view, FRONT International, Cleveland, Ohio, 2018

© Yinka Shonibare CBE. PHOTO: Field Studio

On view through Jan. 26 are more than 40 works made since 2000 by 20 artists from 12 countries. In sculpture, installation, painting, video and other media, the exhibition explores immigration both as a universal human experience and a global crisis of unprecedented size, as, according to the United Nations, 1 in 7 people throughout the world is a migrant either by choice or by force.

Organized by ICA staff members Eva Respini, chief curator, and Ruth Erickson, curator, with Ellen Tani, assistant curator, and Anni Pullagura, curatorial research fellow, the exhibition will begin to travel nationwide next year, appearing first at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and then moving to the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

In Boston, the ICA’s seaport site becomes part of the story, and the exhibition includes a strong local dimension.

In a glassed-in walkway overlooking Boston Harbor, the exhibition concludes with a wall-size placard by artist Michelle Angela Ortiz, who quotes a woman being held at an ICE detention center, who told her, “We are human beings, risking our lives for our families & our future.” The placard faces the shipyard in East Boston that was from the 1920s to the ’50s a major processing and detention center for immigrants. East Boston is home to more foreign-born residents than any other Boston neighborhood, and the shipyard is the location of the ICA’s new Watershed site.

“When Home Won’t Let You Stay” begins in the ICA’s lobby, where Boston artist and educator Anthony Romero has installed a replica of a street vendor’s pushcart. The ICA has also enlisted Romero to coordinate a series of community events that will engage East Boston residents. Other ICA programs related to the show include gallery talks, tours, and workshops in collaboration with Mass Poetry and the International Institute of New England.

Edited by Respini and Erickson, the exhibition’s catalog offers an absorbing companion experience to the show, extending its reflections on home, boundaries, borders and belonging with rich illustrations and thoughtful essays by scholars and artists.

Visible from the elevator as it rises to the fourth-floor galleries that house the show is a large blue banner by Havana-born New Yorker Tania Bruguera entitled “Dignity Has No Nationality” (2017). Founder of Queens-based Immigrant Movement International, an artist-run service center for newcomers, Bruguera has crafted a stitched map of Pangaea, the prehistoric supercontinent that existed before formation of the earth’s seven continents and here, an image of unity transcending political and geographic borders.

Easily overlooked in the first gallery is a small but compelling object by Adrian Piper, a major American artist and philosopher who lives and teaches in Berlin, who has long explored racism and its fictions. She has emblazoned an oval mirror with a statement in gold leaf, “Everything will be taken away,” adapted from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novel “In the First Circle,” in which a prisoner tells his torturer, “The man from whom you’ve taken everything is no longer in your power; he is free again.”

Filling the opposite wall is “Woven Chronicle” (2011-16) by New Delhi-born Reena Saini Kallat, a world map that with electric cord twisted to resemble barbed wire outlines current trade and migration routes. Both an aural and visual experience, the installation emits a low drone suggesting ceaseless movement and an endless flux of exchange that connects and divides us.

Usurping military-grade thermal imaging technology employed in hunting refugees to tell their story, Richard Mosse’s video “Incoming” (2014-17) depicts actual scenes of migration in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa with ghostly, ethereal images of loss, suffering and displacement.

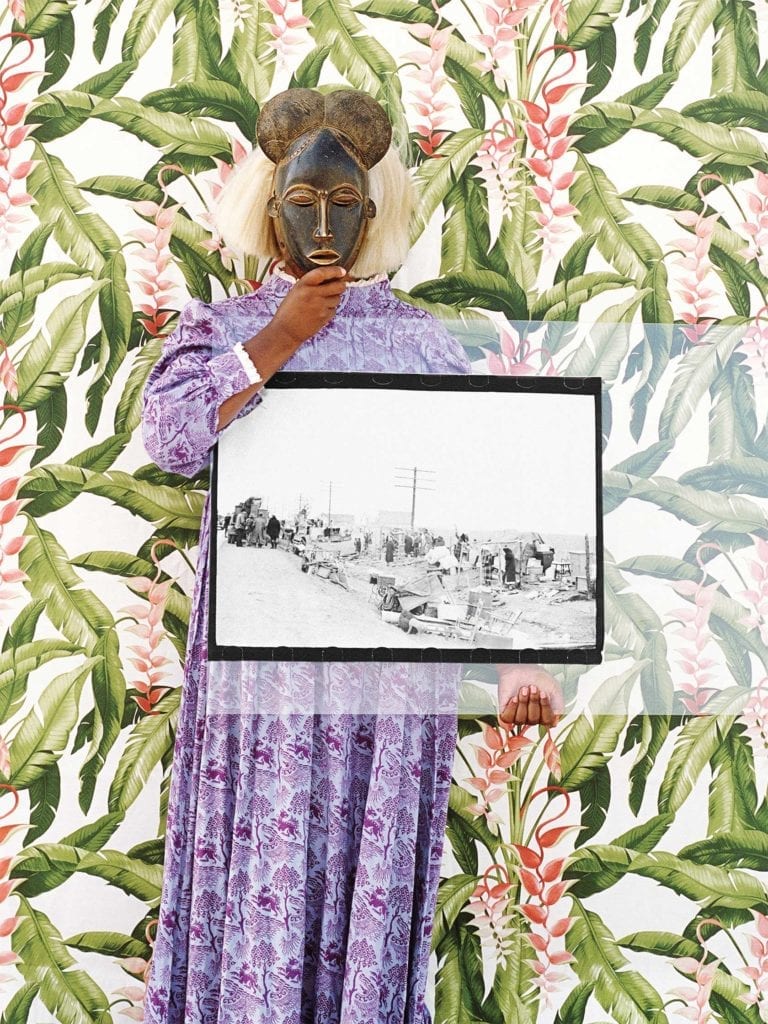

A print by Xaviera Simmons shows the artist posing as a masked female figure in a floral dress against a botanical background that evokes an agricultural setting. She holds a vintage black-and-white photograph of families gathered along an otherwise deserted road with their possessions. They are about to join the Great Migration from the South to seek jobs and lives elsewhere. With her mask, Simmons suggests the duality of being both a subject who is seen and the artist who sees and makes the image.

Do Ho Suh has crafted a series of walk-through replicas of his childhood home in Seoul in translucent yellow and pink polyester. Their blend of ephemeral fabric and precisely wrought dimensions evoke the chimera-like nature of memory.

With an assortment of blue clothing arranged on the floor, Kader Attia’s “La Mer Morte (The Dead Sea)” (2015) suggests rippling waves and memorializes those lost at sea while attempting to escape war-torn homelands in fragile, overcrowded boats.

The U.S.-Mexico border is the focus of Guillermo Galindo and Richard Misrach’s multi-year collaboration, “Border Cantos” (2004-16), which includes Misrach’s haunting photograph of the wall meandering ribbon-like between a brooding sky and rolling hills. Nearby are raw sculptures that Galindo forged from discarded segments of the wall as well as left-behind gear and animal skeletons.

Adaptation to a new home is a creative act rivaling any artistic endeavor, and Aliza Nisenbaum’s large oil paintings celebrate an immigrant family she has befriended by rendering their daily life in the joyful palette of Mexican majolica tiles.

British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare CBE has created an eloquent tribute to America as a nation of immigrants. Occupying an entire gallery is his “The American Library” (2018), a floor-to-ceiling installation of more than 6,000 books, each bound in Dutch wax cloth and imprinted in gold leaf with the name of a notable contributor to American history who is a first- or second-generation immigrant or descendant of participants in the Middle Passage or Great Migration. These individuals are as varied as W.E.B. DuBois, Toni Morrison, Steve Jobs and Donald Trump. Shonibare underscores his theme of multicultural hybridism with the fabrics covering the volumes—West-African batiks printed on Indonesian cottons imported through Dutch and English trade.

Workstations enable visitors to access the installation’s website to learn more about the people whose names appear on the bindings and add their own family migration stories. After all, with the exception of the country’s surviving indigenous peoples, every American is an immigrant.