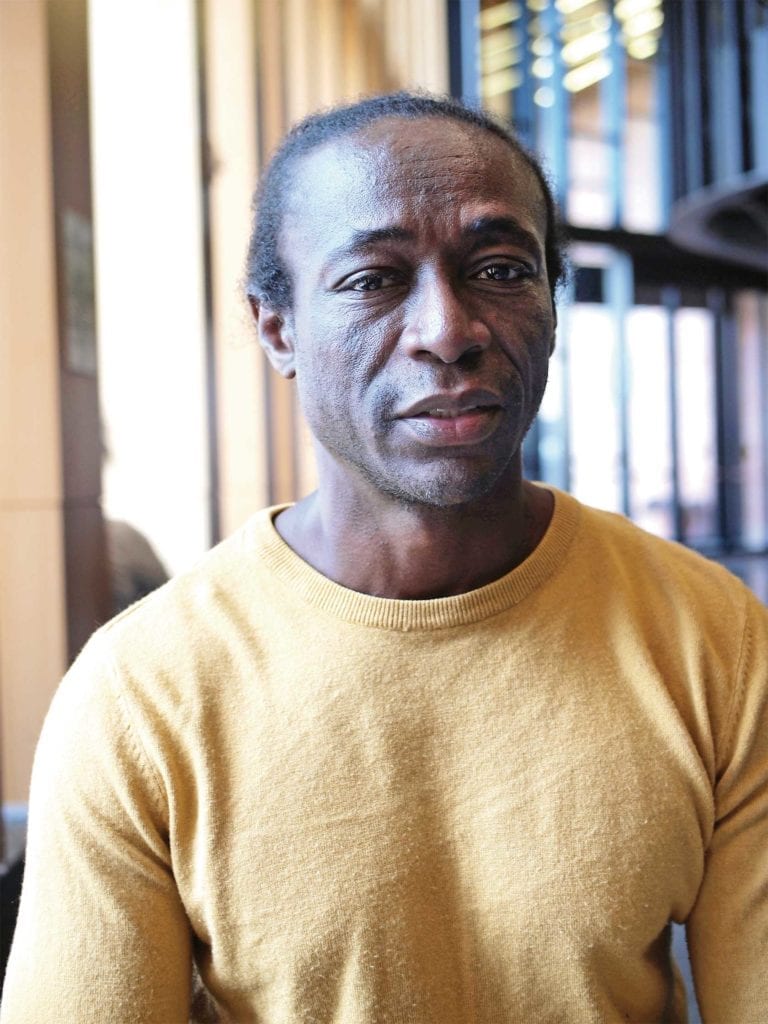

By 2018, Omar Suazo was used to death threats. As the popularly elected president of the Patronato, or governing body, in the largest Garifuna community in Honduras, Suazo had stood in the way of three attempts to dam the Sambo Creek river and had fought against drug dealing and land expropriation — two forces that he said were eating away at his community.

On April 18 of last year, as Suazo was entering a nightclub in the town of Sambo Creek, an assailant appeared, ready to make good on the death threats. In a matter of seconds, José Leonardo Villafranca Mejía stabbed Suazo four times in the back, then was shot by an unidentified bystander.

If Suazo had any doubts as to how Honduran officials felt about him, what happened next would certainly dispel them. Suazo was arrested for the murder of his assailant, then denied medical treatment, despite his wounds.

Suazo’s ordeal, which included a 16-month stint in prison, is emblematic of the relations between his Garifuna community and the Honduran government. Conflicts go back more than 200 years to when Suazo’s ancestors first settled on the Atlantic coast.

The Garifuna people, also referred to as Garinagu, are an Afro-indigenous group descended from survivors of a 1675 slave shipwreck off the coast of St. Vincent and Maroons who escaped slavery in other Caribbean islands as well as indigenous Carib and Arawak populations. The Garinagu fought the British intermittently over the next 100 years, finally reaching a truce in 1796, when, outgunned, they agreed to a permanent exile from St. Vincent and settled in what is now Honduras. There, they allied with the Spanish and fought against British military and pirate attacks.

The Garinagu remained allied with the Spanish, even as colonists in Central and South America fought against Spanish colonial rule. That alliance contributed to the group’s marginalization in post-colonial Central America.

Currently, the Garinagu live primarily along the Atlantic coast of Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Belize. Their language contains a mixture of African, Arawak and Carib languages. French, Spanish and English words have also entered their lexicon as a result of trade.

The historic marginalization of the Garinagu in Honduras took a turn for the worse in 2009, when right-wing President Juan Orlando Hernández took power following a U.S.-backed coup that ousted democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya.

Once in power, Hernández made concessions for mining, hydro-electric dams and other land uses that pitted indigenous populations there against large corporations and contributed to the country being listed as the most dangerous country in the world for environmental activism.

It may well have been Suazo’s opposition to three separate proposals for hydro-electric plants on the Sambo Creek river that put him in the crosshairs of whoever hired Villafranca Mejía to kill him.

In the most recent hydropower proposal, a Honduran firm had sought funding from Japanese financiers for the construction of a dam. Suazo took his case to the Japanese.

“We visited the Japanese embassy and explained the problem,” Suazo told the Banner in a recent interview. “They said they wouldn’t finance it.”

In jail, Suazo recovered slowly from his stab wounds, but received scant medical attention. He eventually contracted meningitis and remained ill for much of the 16 months he was behind bars.

He had obtained U.S. citizenship during the 1990s, while living in Boston. Members of the Boston area Garingu community appealed to local elected officials, including former U.S. Rep. Michael Capuano and Boston City Councilor Ed Flynn, both of whom were instrumental in successfully pressuring the Honduran government to release Suazo.

After his release and return to Boston in 2018, however, Honduran officials re-opened the case against him. In a Kafkaesque turn, Suazo has again been charged with the murder of Villafranca Mejía.

Now, he is determined to return to Honduras, despite the arrest order. Watching events in Sambo Creek from afar, Suazo, who is now living with his wife in Dorchester, says he cannot bear to sit on the sidelines.

“People are scared,” he said. “I need to talk to people about how they can stand up to fight the government. I don’t know what the consequences will be. I know we have to fight to save our community.”

In addition to the push for hydro-electric dams in Honduras, the Garinagu in Central America face pressure from other forces: real estate developers looking to cash in on the beachfront property in which the communities reside; palm oil plantations seeking to expand into their land; and narco-traffickers who use the lands as trans-shipment points for their trade with U.S. markets.

Despite the threat of death or re-arrest, Suazo says he is not afraid.

“I have learned that in life, whatever happens is for the best,” he said. “I believe in God. I believe in my ancestors. They keep me working to help my community.”