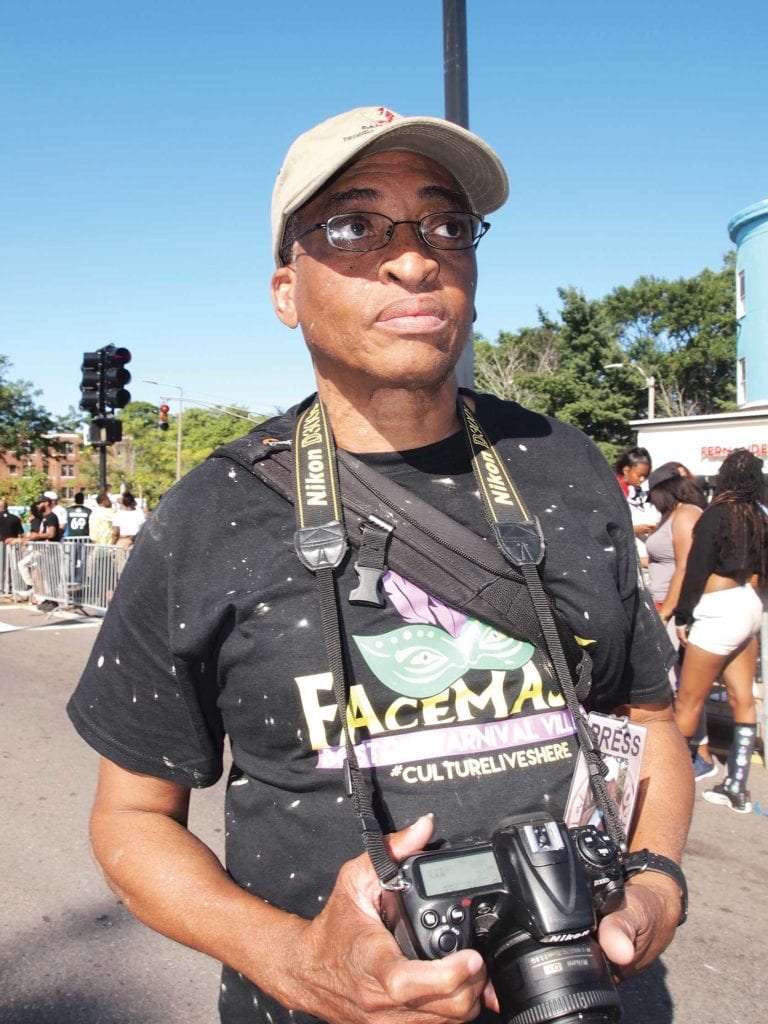

If you have ever been to a Caribbean Carnival, you probably remember a lot of vibrant colors, feathers and sequins — little is off-limits in the Carnival parade. The experience of attending Carnival cannot be fully described in words, which is why the glossy pages of Michael Smith’s new book, “Culture Lives Here,” are filled with photographs from Boston’s Trinidad-style carnival that capture the tradition.

Published just last Friday on BookBaby, the book can be purchased from the bookbaby.com store. Its 310 pages span Boston’s Carnival from 2005 to 2015, from Jouvert and the Kiddies Carnival to the parade itself. The book also describes some of the history of Boston’s Carnival and includes information on the artisans who create breathtaking costumes and floats for the parade every year.

Smith was born in San Juan, Trinidad, just a few miles from Port of Spain, the capital. He immigrated to the United States through Saint Croix in 1977 and graduated from Northeastern University with a BSEE degree in electronic engineering just six years later. He has worked as an electronic engineer ever since and owns a home in Milton, where he has lived for more than 20 years.

Smith has participated in Carnival since he was a child. His earliest memory of the event, he says, was waking up to watch the Jouvert revelers in Port of Spain, where he would also watch the parade of the bands with his grandmother. Smith also loved visiting the masquerade band camps — known as mas’ camps — and watching the artisans work, then seeing the masqueraders bring the costumes to life when they paraded down the street.

Smith played mas in the Boston Carnival with Mislet Productions for two or more Carnival seasons before he moved on to documenting the events through photography.

He says he’s always been interested in photography, but never had the means to pursue it until after college. When asked why he began photographing Boston’s Carnival he said, “I decided to document the carnival because I think in the future those photographs will serve as a historical reference and demonstrate what the Caribbean people brought to Boston through the people of Trinidad and Tobago.”

The tradition Trinidadian and Tobago people brought to Boston stems from a history rooted in slavery.

“Carnival is a byproduct of slavery which started with the Jouvert, meaning break of day, and represented the old — or as we call it “Old Mas” — and the new as “Pretty Mas” costumes, representing a renewal,” he said.

Smith says Carnival was created by a people whose traditional instruments were taken away by slave masters. Out of that came the invention of the steelpan, as well as Calypso and soca music, some of the most popular West Indian musical forms.

Today, Carnival has evolved beyond Trinidadian culture. Smith says Carnival now seems designed for the commercial market, with an emphasis on the female body. Traditionally, costumes were more elaborate and theme-specific.

However, Boston’s Carnival is unique in that it includes many Caribbean islands, not just Trinidad and Tobago. Smith notes that Ken Bonaparte Mitchell, the founder of the Boston Carnival, changed the name of the event to what it is today in order to include other Caribbean cultures.

“That is one distinct characteristic of Boston Carnival I appreciate,” Smith says. “However, I also believe in order to foster that growth to attract the other islands and others to participate, the standards used to judge a traditional Trinidad-style band cannot be used for the other islands’ bands, since their qualities and standards are different, but no less enjoyable and interesting.”

Smith thinks that 46 years after its founding, Boston Carnival should be spread across the city. He says the world’s first and annual King and Queen Show could be held at TD Garden Boston; a steelpan festival could be held on the Roxbury Community College campus; and workshops could be held in the mas’ camps to teach young people the art of costume-making and other skills.

When asked about the current leadership of the Caribbean Carnival, Smith said the organization needs new blood.

“Someone who understands the culture and its significance in Boston’s cultural diversity is needed immediately,” he explains.