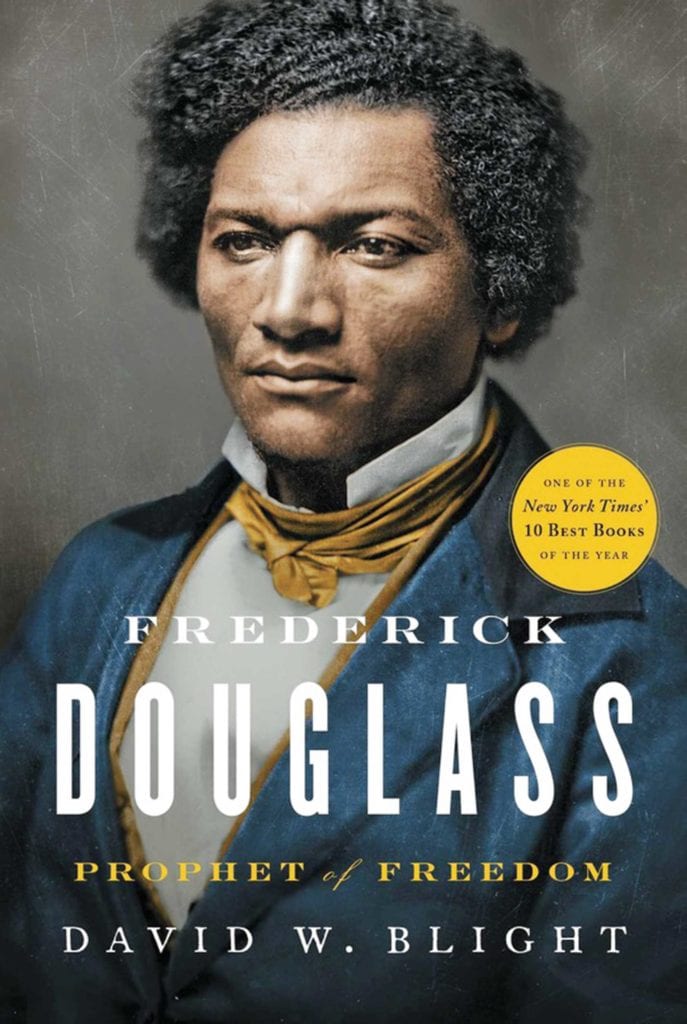

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018. Pp. 888. Cloth. Illustrations. $37.50)

On Tremont Street in Lower Roxbury there is a building with a mural on it. It features the likeness of Frederick Douglass. Who was Frederick Douglass?

In this biography, David W. Blight, Professor of History and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University, answers this question. Douglass was one of America’s most important social reformers. Born a chattel slave on a Maryland plantation in 1818, Douglass died a highly respected American citizen in 1895. Blight captures in vivid detail the rise of Frederick Douglass from obscurity to prominence.

Douglass was a self-educated man. With some rudimentary alphabet lessons from his slave mistress and white playmates, the Bible and the Columbian Orator developed his speaking, reading, and writing skills. These skills enabled him to write three autobiographies about his struggles against American slavery and racism and for African American citizenship.

In 1845, his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave was published while living in Lynn, Massachusetts. He was a fugitive slave. In 1855, now a free man and a resident of Rochester, New York, he issued a revised autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom. He was a leader of the abolitionist movement. In 1876, the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass chronicled his journey to becoming one of the more prominent citizens of Washington, District of Columbia. He was a leading member of the Republican Party.

Preacher

A much sought-after speaker, Douglass received his preaching license from the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in New Bedford, Massachusetts where he, a fugitive slave, and his wife, Anna Murray, a free African American from Baltimore, settled in 1838. It was around this time that Douglass became a protégé of William Lloyd Garrison and joined the abolitionist movement as a featured speaker.

Douglass shared the abolitionist belief that the most immoral of desires is that desire to have absolute control over another human being. He embraced the abolitionist strategy of moral suasion to change the hearts and minds of people as pre-requisite to changing societal laws.

Douglass gave witness to the inhumanity and sinfulness of slavery in his speeches. During a book tour of the British Isles, several English admirers raised the $711 to purchase his freedom from the Auld family of Maryland.

Upon his return to America, Douglass moved his family to Rochester, New York where he began his emergence as the first and foremost of African American leaders. He had a prophetic voice like the Old Testament prophets Jeremiah and Isaac. He lectured extensively. His 1852 “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” lecture to the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester was one of the most compelling critiques of slavery.

Douglass published two significant abolitionist newspapers. The first newspaper was the North Star which he co-founded with Martin Delaney, a Harvard Medical School educated black nationalist. He shared with Delaney a commitment to racial uplift and improvement. The second newspaper was Frederick Douglass’ Paper. His editorial assistant was Julia Griffiths, an Englishwoman, and one of his financial benefactors was Gerrit Smith, a wealthy New York politician.

Douglass believed in speaking truth to power. In a significant split with Garrison, he moved from moral suasion to political action. He concluded that the American Declaration of Independence and Constitution were anti-slavery documents. These documents provided a political solution to the slavery problem. Slavery was a function of wealth, prestige, and power.

Although violence or the threat of violence enforced slavery, politics legitimated and sustained Slave Power such as the Compromise of 1850 and its Fugitive Slave Law. Only a change in the politics of the country would lead to the destruction of slavery. He supported anti-slavery political parties including the Republican Party. Douglass also believed, in a democracy, that all were welcomed and equal. He was a strong supporter of women’s rights.

Douglass welcomed the Civil War as a fulfillment of God’s promise to enter history to right an injustice. He wrote editorials and gave speeches in support of the war. He celebrated President Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation at Twelfth Baptist Church, an African American church in Boston. He encouraged African American men to join the Union army. Two of his sons served in the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. And most importantly, he pushed for citizenship as a birth right for African Americans.

Public life

After the Civil War, he remained engaged in public life. He continued lecturing and writing. The “Self-Made Man” was one of his more popular topics. He served as president of the Freedman’s Saving Bank. He campaigned for Republican presidential candidates Ulysses Grant and Benjamin Harrison. He was appointed United States Marshall for the District of Columbia and, later, Register of Deeds for the District of Columbia. He diplomatically represented the United States in Haiti and Santo Domingo.

Douglass was a committed Republican. It was the congressional party that abolished slavery, defined citizenship as a birth right, and extended voting rights. The Republican Party of the nineteenth century was the party of inclusion, social mobility, and democratic rights. In contrast, in many parts of the country, the Republican Party of the twentieth first century is the party of intolerance, bigotry, voter suppression, and cruel indifference to human pain and suffering.

On February 20, 1895, Frederick Douglass died of a heart attack. He was at his home with his second wife, Helen Potts, a white woman. He was scheduled to give a lecture at a black church that evening. Upon learning of his death the next day, the United States Senate adjourned in his honor. His body was buried in Rochester, New York, in the family plot next to his first wife and his daughter.

In writing this informed and inspiring biography, Blight brings to life the Tremont Street mural of Frederick Douglas. Both popular and academic readers will enjoy getting to know this intimate portrait of Frederick Douglass.

Lester P. Lee, Jr. is a Senior Lecturer in History at Suffolk University