Big changes in Boston’s electoral map

Pressley, Rollins victories underscore demographic shifts in neighborhoods

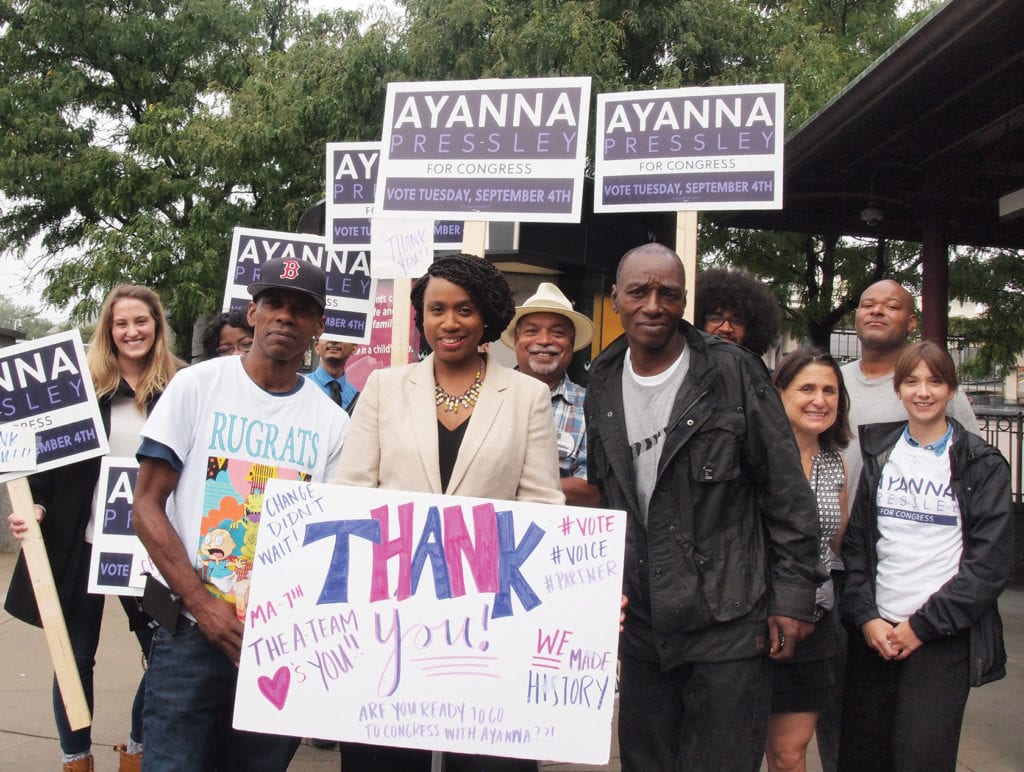

Last Tuesday’s historic election saw Boston voters send City Councilor Ayanna Pressley to Congress, Rachael Rollins to the Suffolk County District Attorney’s office and Nika Elugardo to the State House.

Each candidate benefitted from a surge of progressive voters that signals a new map for Boston elections.

In decades past, voter turnout in Boston followed a doughnut-like pattern where the neighborhoods at the center of the city — Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain and the South End — posted lower-than-average voter turnout, while those on the periphery — South Boston, the Neponset and Savin Hill neighborhoods of Dorchester, Hyde Park, West Roxbury, Charlestown and East Boston — posted the highest numbers.

That pattern gave the predominantly white working- and middle-class neighborhoods disproportionate power to determine who got elected in the city. When former state Rep. Mel King formed his Rainbow Coalition of voters of color and white progressives during his 1983 run for mayor, the numbers worked against candidates of color like King, who lost to Ray Flynn by a 2-to-1 margin that year.

This year, the Sept. 4 primary, with stunning upset victories by Pressley and Rollins, demonstrated just how much the city’s demographics and political landscape have changed.

Relatively high turnout and strong support in Boston’s predominantly black wards and precincts contributed to Pressley’s impressive 59 percent to 41 percent victory over incumbent U.S. Rep. Michael Capuano. In Boston, where Pressley garnered 64 percent of the vote, the predominantly African American and Latino wards 12 and 14 delivered her 79 and 78 percent of the vote, respectively.

Pressley won every other Boston ward, although Capuano won some precincts in working class white strongholds including Orient Heights and Cedar Grove.

Voter turnout

Citywide, voter turnout on Sept. 4 continued a downward trend. Turnout this year was 100,333, or 25 percent of Boston’s 403,560 registered voters. In Roxbury, Ward 12 voters voted one percentage point below the city average at 24 percent. But in South Boston, where turnout has historically been higher than average, turnout was just 21 percent in Ward 6 and 22 percent in Ward 7.

By contrast, turnout in wards where state Rep. Jeffrey Sanchez and challenger Elugardo faced off was considerably higher. In Ward 10, which includes Mission Hill, turnout was 27 percent. In Ward 19, which includes the Pondside and Moss Hill sections of Jamaica plain, turnout was 40 percent — the highest in the city.

Interestingly, JP’s Ward 19 also gave Suffolk County District Attorney candidate Rollins her highest percentages: 59 percent of the vote. Rollins won with 40 percent of the vote in Boston and 39 percent across Suffolk County, defying pundits who favored Greg Henning — the sole white man in the race — to win. Henning garnered 23 percent of the vote county-wide and 22 percent in Boston.

In Ward 12, where the predominantly African American electorate gave black candidates Evandro Carvalho and Linda Champion some support, Rollins garnered a commanding 48 percent of the vote. Carvalho had 30 percent. Henning, just 6.6 percent.

Outside of Ward 19, Rollins also performed well in the Fort Hill section of Roxbury, winning 61 percent of the vote in Ward 9, Precinct 5 and 66 percent in Ward 11, Precinct 1. In all, she won 60 percent of the votes in Ward 11, which runs from Fort Hill to Forest Hills in Jamaica Plain.

Henning’s strongest support came from the neighborhoods that traditionally determined the winners, with margins as high as 70 percent in some South Boston precincts. In ward 16, which includes the Cedar Grove and Neponset sections of Dorchester, Henning won with 45 percent of the vote. He garnered his highest margin of victory in any precinct in Ward 16, Precinct 12, where he won 79 percent of the vote.

That precinct, which has a high concentration of police officers and fire fighters, also delivered Donald Trump his highest percentage anywhere in Boston during the 2016 presidential election: 46 percent.

What’s changed?

The gentrification of South Boston has put a major dent in the neighborhood’s working- and middle-class voting base. That becomes evident when the Seaport District, Ward 6, Precinct 1 is taken into account. Because the area was largely empty before condo buildings went up in the first decade of this century, most of the 5,576 registered voters in the precinct are new arrivals. Just 15 percent of those dwelling among the tech workers and well-heeled luxury condo residents there deigned to sully their hands with a ballot Tuesday.

While South Boston’s newcomers are concentrated in Precinct 1, they’ve spread throughout the district, mixing in with indigenous South Boston residents and driving down turnout throughout wards 6 and 7. Thus, Henning’s impressive margin of victory in the South Boston precincts was tempered by the neighborhood’s tanking turnout.

Meanwhile, Rollins likely benefitted from the pitched battle between Elugardo and Sanchez, which energized both candidates’ progressive-voting bases: Sanchez’s Mission Hill and Hyde Square stronghold, and Elugardo’s in the Pondside neighborhood. In all, 7,905 voted in the 14th Suffolk District — the highest turnout in any Boston legislative race. In contrast, just 5,368 people voted in South Boston’s 4th Suffolk District primary in South Boston, where David Biele bested Matt Rusteika.

Rollins may also have benefitted from a surge of interest in Pressley’s challenge to Capuano among black and Latino voters, as well as among white progressives. Rollins also benefitted from a substantial ground game. Her campaign volunteers were augmented by a network of criminal justice reform organizations, the Right to the City Coalition, Progressive WRox/Roz and Jamaica Plain Progressives.

The latter group organized regular canvasses on behalf of Rollins, Elugardo and Pressley, printed and distributed lists of their endorsed candidates and conducted an aggressive social media campaign on their behalf.

Pressley, Rollins and Elugardo maintained campaign offices within blocks of each other in a quarter-mile stretch of Centre Street between Hyde Square and Jackson Square. Their campaigns and the activism of the groups that supported them contributed to what some Jamaica Plain residents described as “armies of canvassers” that crisscrossed the neighborhood throughout the summer.