Life in their hometown has an inveterate impact on the development of the young. In the Great Migration of six million blacks from the South between 1910 and 1970, families were uprooted because of racial bigotry and the lack of economic opportunity. While there was not an abundance of good paying jobs available to blacks in Boston during this time, there was no major exodus of blacks from Boston.

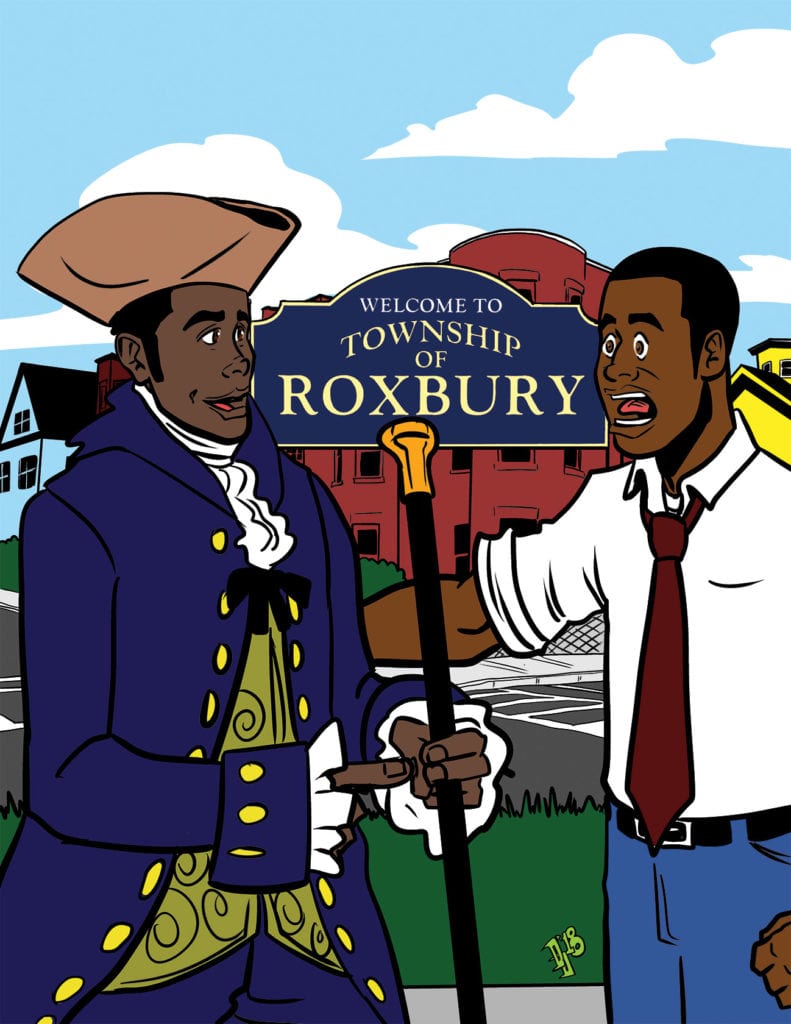

It is difficult to grow up in Boston without becoming aware of the historical significance of the city and the role of black citizens. Crispus Attucks, a slave from Framingham, was the first to die on March 5, 1770 in the conflict that resulted in the Revolutionary War of 1775. Blacks living in the villages and towns around Boston were heroic partisans.

Although the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth aboard the Mayflower in 1620, the ship that carried the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony arrived on the Arbella in Salem Harbor ten years later in 1630. This established the British colony against which the people would rebel.

Aboard the Arbella was Thomas Dudley, who would become the royal governor of the colony. He was a resident of Roxbury, the most flourishing town in the colonial Boston environs. Dudley was one of the first of Roxbury’s prominent residents.

Blacks first came to Boston in 1638 as slaves, but over the years some of those who came were freedmen. In 1783, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the state constitution no longer permitted slavery in Massachusetts. However, there was a battle as to whether the state law could supercede the absence of a federal prohibition. There were a number of judicial cases involving the federal Fugitive Slave Act.

Many upper-class whites in Boston joined the antislavery movement. In those days blacks then lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill. They later moved to the West End, the South End and then to Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan.

Over the years, many whites have protested to prevent racial discrimination in the state even without the alliance of blacks. Whites voted in 1780 to approve Article I of the state constitution that would force the courts to rule against slavery. They also supported efforts in negotiating the U.S. Constitution to reduce the impact of the slave states in the federal government.

Boston became national headquarters of the antislavery movement. William Lloyd Garrison, the white publisher of “The Liberator,” became a prominent spokesman. When Benjamin Roberts, a black citizen, brought suit in 1849 to prevent racial discrimination in public schools, he was represented by Charles Sumner, who later became U.S. senator, as well as a prominent black lawyer, Robert Morris, Sr. He lost the case, but in 1855 the state legislature enacted a law against racial discrimination in schools.

Moorfield Storey, a white lawyer from Roxbury, became the first president of the NAACP in 1915. Now a century later, there is still a tradition in Boston of a multiracial affiliation for full equality. Despite numerous setbacks, this commitment to human rights continues. It’s a Boston thing that survives despite persistent vestiges of racial discrimination.