Curators plan exhibitions years in advance, but they have a funny way of becoming specific to our moment. On view through Sept. 30 at the ICA Boston, “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85” feels painfully relevant.

Jan van Raay, Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum, 1971. photo: Courtesy the artist, Portland, OR, 305-37. © Jan van Raay

“The exhibit highlights the activities and priorities of women of color during this period, when they were largely excluded from the feminist movement,” says ICA curator Jessica Hong. The show originated at the Brooklyn Museum and has made its way around the country at this crucial time. The ICA is its last stop.

Faith Ringgold, Early Works #25: Self-Portrait, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Elizabeth A. Sackler, 2013.96.

Photo by Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum. © Faith Ringgold

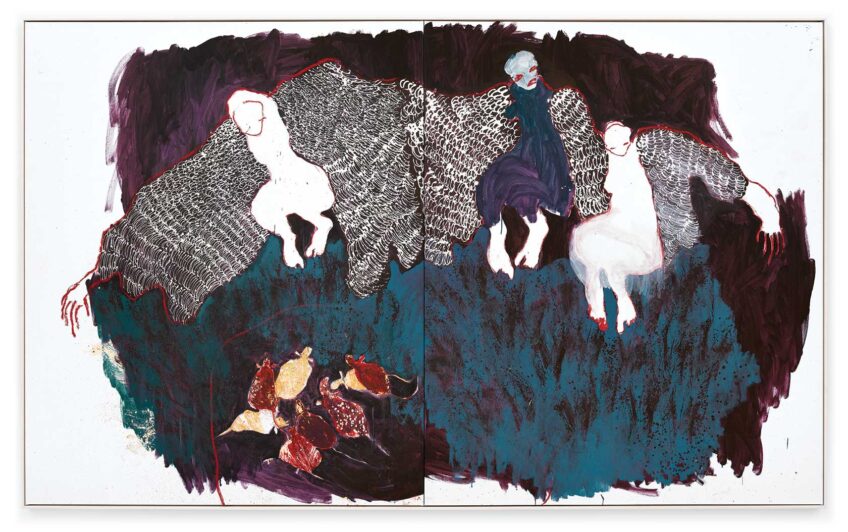

Rebelling against the white-centrism of second wave feminism, these artists of color started their own collectives and fought for their own change. “Black Radical Women” is part art exhibit, part history lesson. The bold paintings and searing sculptures are paired with photographs of collectives, shows and power players in the movement.

“You can see the dire need for an exhibition like this that sheds light on cultural movements. They all harness their art as political power,” says Hong.

“Revolutionary Sister,” a mixed-media wall construction on wood by Dindga McCannon depicts the ideal fellow fighter. A bold woman painted in bold colors, she wears bullets at her hip and stakes in her hair made from recycled flagpoles. Her shape brings to mind the statue of liberty, begging the question, where’s the freedom for African Americans? McCannon wrote about the piece, “My warrior is made from pieces from the hardware store — another place women were not welcomed back then. My thoughts were my warrior is hard as nails.”

McCannon’s piece focuses on fighting, on finding a solution. Other artworks highlight the problem. Lorna Simpson’s gelatin silver print photograph “Waterbearer” depicts a black woman in a white dress from behind. She’s pouring out water with abandon from two jugs, one in each hand. Underneath the photograph, in vinyl lettering, it says, “She saw him disappear by the river. They asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” All women, but particularly black women, know that feeling of discounted memory.

Jae Jarrell, Ebony Family, circa 1968. Velvet dress with velvet collage, 38½ x 38 x 1/2 inches (97.8 x 96.5 x 1.3 cm).

photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum. © Jae Jarrell

The exhibit, which, though relevant, is still rooted in a historical moment, provides an interesting conversation with its neighboring exhibit, “Love is the Message, The Message is Death,” by Arthur Jafa. A contemporary filmmaker, Jafa’s work comments on the experience of being black in the United States today. The exhibits together highlight what has changed — and more importantly, what hasn’t.

Many of these artists are still living and working. Looking at the works, one can’t help but wonder what they have to say now. Hong says, “These artists are finally getting their due after so many decades.” And now more than ever, the voices of black women are needed.