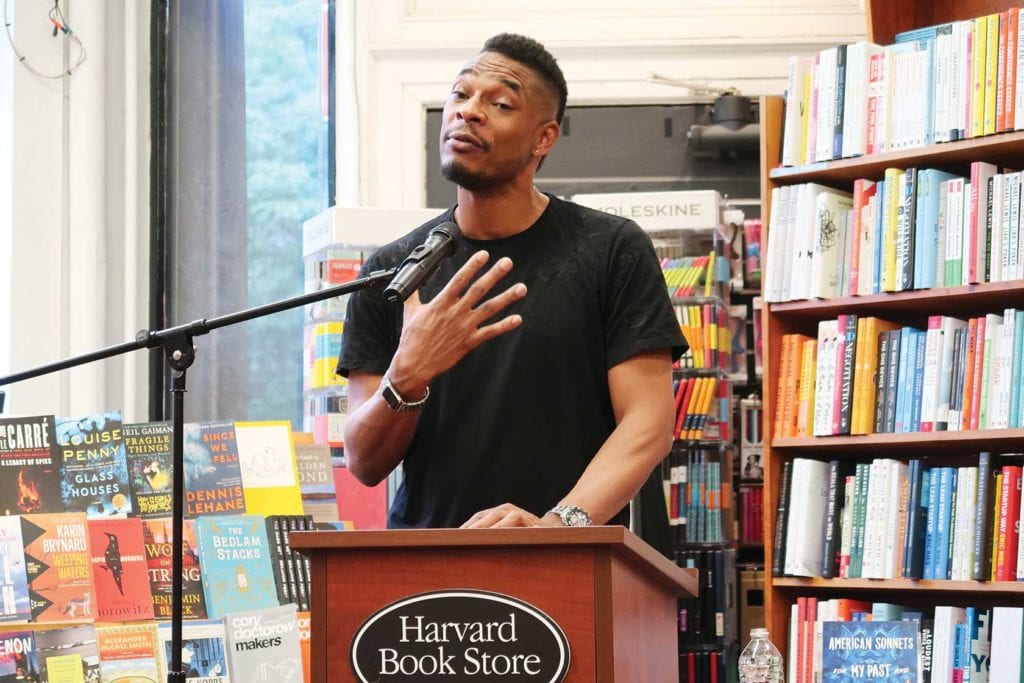

At Harvard Book Store in Cambridge last month, award-winning poet Terrance Hayes read selections from his latest book, “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin.”

Hayes wrote the collection of 70 sonnets during the first 200 days of the Trump presidency. Many address his potential assassin — racial violence in this country, as well as various forces that corrode intelligence, spirit and compassion.

Exploiting the double meaning of “kill,” which can be slang for slaying an audience with pleasure, Hayes pointed out that some of the sonnets focus on what he greatly enjoys — “All the things that kill me.”

The book is the sixth by Hayes, 47, whose poems explore in everyday language the life of black men in America. A 2014 MacArthur Fellow and recipient of the 2010 National Book Award for his poetry collection entitled “Lighthead,” Hayes is poetry editor of the New York Times Magazine and a distinguished professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh.

Speaking with a lilt from a South Carolina boyhood, Hayes is tall and handsome, and has the bearing of an athlete (Academic All-American in men’s basketball at Coker College) and the easy congeniality of someone who is comfortable reading his poems in settings as varied as Carnegie Hall and the New Orleans Parish jail.

Both a poet and a visual artist, Hayes is inventive with words and the form they take on a page. In his book “How to Be Drawn,” a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award, he puts the words of a poem about Etheridge Knight, a distinguished poet who published his first book while serving an eight-year prison sentence, inside the boxes of a police crime report. In the “Lighthead” collection, his 20-stanza poems mimic the rigid format of a PechaKucha, a 20-slide business presentation style that originated in Japan, where he taught for a few years.

Hayes finds in the 14-line sonnet form, fashioned in the Italian court in the 13th century (sonetto:“little song”), an agile, intimate vehicle for voicing the state of 21st-century America. The sonnet usually expresses a single sentiment and in its concluding lines takes a turn that reflects on its subject, often with a new and surprising perspective.

The pleasure Hayes finds in the sonnet form was evident in his reading and in his comments about the process of writing the book. Speaking of a very different project, his three-year work to craft a 1,000-line poem about abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Hayes said that with this sonnet collection, “I tried not to over-think, and let myself trust language and trust my intuition.”

As if taking the original name for a sonnet, “little song,” to heart, the selections Hayes read varied between personal arias and essays on the state of the nation with language rich in humor, bite and occasionally, tenderness.

Hayes frequently spoke of other poets, and his book pays tribute to Wanda Coleman, a native of the Watts district of Los Angeles who found in her experience as a black woman living below the poverty line in LA a source of poetry. Revered by fellow poets, Coleman was known as the “unofficial poet laureate of LA” and was nominated as California poet laureate.

In his acknowledgements, Hayes writes, “These poems owe tremendous gratitude to the great Wanda Coleman (1946-2013),” and in the preface, Hayes quotes her aspiration: “Bring me to where my blood runs.”

Hayes has fun with the form. His wordplay mingles the political and the personal and juggles familiar words and phrases into new brews that evoke unexpected associations and mix rage, violence and humor in the same line. One sonnet he read begins:

“Aryans, Betty Crocker, Bettye Lavette,

Blowfish, briar bushes, Bubbas, Buckras,

Archie Bunkers, bullhorns, bullwhips, bullets,

All cancers kill me, car crashes, cavemen, chakras,”

“I think of the sonnet form as writing a letter,” Hayes told the audience. Some are addressed to himself, the nation, or a potential assassin. Even a stinkbug gets a sonnet, which Hayes read with pride.

The 2016 presidential election was the backdrop for this book, but only once Hayes spoke of politics, commenting, “This is a democracy—we’re always responsible for everything, even other people’s idiocy.” Otherwise, he let his sonnets do the talking. The most explicit reference to the election was one that he addresses to fellow citizens:

“America, you just wanted change is all, a return

To the kind of awe experienced after beholding a reign

Of gold. A leader whose metallic narcissism is a reflection

Of your own. …”

The poem concludes:

“May your restlessness come at last to rest, constituents

Of Midas, I wish you the opposite of what Neruda said

Of lemons, may all the gold you touch burn, rot & rust.”

Asked if he recalled writing his first poem, Hayes readily said yes. He was 12 years old, and he wrote the poem to impress a girl named Christy Tucker. The poem failed, he said, “but I liked the process of building something.”