Democrats face push from left

Democratic incumbents face challenges from party’s left wing

That state Rep. Angelo Scaccia has challengers is not a surprise. The conservative-leaning Hyde Park Democrat was first elected in 1973 and represents a district with a voting population that has shifted from majority Italian American to majority people of color.

Among those who have pulled papers to take on Scaccia, one of the longest-serving representatives in the House, are criminal justice reform activist Segun Idowu and former Women’s Bar Association president Gretchen Van Ness.

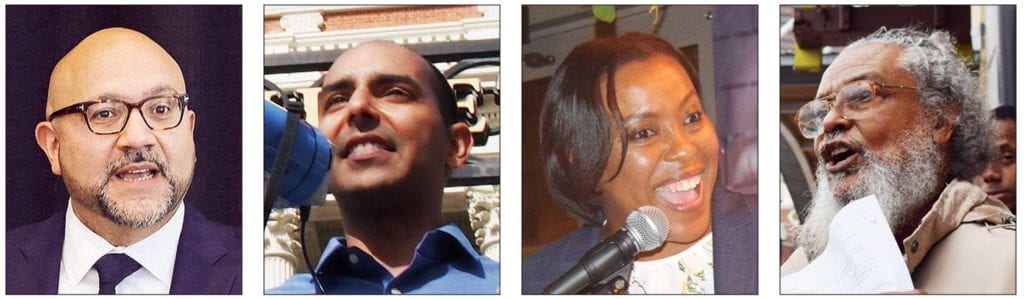

But Scaccia isn’t the only long-term incumbent House member facing a challenge. Jamaica Plain Rep. Jeffrey Sanchez and South End Rep. Byron Rushing are facing their first challengers in years. Rushing’s opponent, Jonathan Santiago, is a physician working at Boston Medical Center who is active in progressive causes and in the Ward 9 Democratic Committee. Sanchez’s opponent, Nika Elugardo, a former legislative aide to Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz, has led anti-human-trafficking and youth violence prevention campaigns.

Rep. Liz Malia, who easily fended off a challenge from former radio host Charles Clemmons Muhammad in 2016, is facing a challenge from Ture Turnbull, executive director of MassCare, a campaign for a single-payer healthcare system in the state.

Along with At-large City Councilor Ayanna Pressley’s challenge to 7th Congressional District Rep. Michael Capuano, District 8 City Councilor Josh Zakim’s challenge to Secretary of State William Galvin, and paralegal Katie Forde’s challenge to Suffolk County Register of Deeds Stephen Murphy, the four House challengers represent a push from the left wing of the Democratic party that mirrors a similar leftward push at the national level with proponents pushing for single-payer health care, wage support for low-income earners and more liberal immigration laws.

In Massachusetts, candidates on the left wing of the party are pushing back against what many see as the Legislature’s politically conservative Democratic leadership.

“We’re always being told to wait, but as we’re waiting, this country is going to sh–,” says Jordan Berg Powers, executive director of Mass Alliance, a progressive political action network. “We’re always being told to wait. We hear ‘That’s not how it works.’ We can’t create change at the pace we’re going at.”

Powers and other political observers cite criminal justice reform, single-payer health care and progressive tax reform as issues the Legislature has lagged on. While legislators did pass a comprehensive criminal justice reform bill in April, the reforms fell short of what advocates sought, and mandatory minimum sentences were added for opioids.

“The criminal justice reforms the Legislature passed just catch us up to where other progressive states are,” Powers said.

Democratic majority

With Republicans holding just seven of the 40 seats in the Senate and 34 of the 160 seats in the House, Massachusetts is one of the most solidly Democratic states in the nation. Over the past 50 years, the state has consistently backed Democratic presidential candidates.

In decades past, Massachusetts made significant investments in public transit infrastructure and public K-12 and higher education. But starting in the 1990s when Republican governors and Democratic legislators made a series of cuts to the state’s income tax rate and taxes on investment dividends and interest, the state’s revenues have not kept pace with the cost of maintaining those investments. The rapidly increasing cost of health care and declining revenue from the sales tax have exacerbated the revenue shortfalls. A legislative committee found that the state is underfunding K-12 education by more than $1 billion a year. Massachusetts residents in public colleges and universities are burdened with increasing tuition and fees, and the MBTA system and regional public transit authorities are struggling with maintenance backlogs and equipment failures while faced with increasing demand.

While some on Beacon Hill, including former Gov. Deval Patrick, have made attempts at reforming the state’s tax system to restore revenue to public investments, there is a general lack of support in legislative leadership.

“We’ve had seven years of sustained economic growth and we’re not putting enough money in the rainy day fund or investing in progressive causes,” notes former state Democratic Party Chairman John Walsh, who backed Setti Warren’s aborted campaign for governor.

Centrist orientation

With power concentrated in the hands of House Speaker Robert DeLeo, a Winthrop Democrat who regularly opposes progressive reforms and new taxes as if seeking some middle ground between the Democratic majority and the conservative fringe in the Legislature, the consolidation of power that began more than 20 years ago under then-Speaker Thomas Finneran has continued. In 2015, DeLeo led the House in a vote to abolish term limits for the post.

It took a state-wide grassroots movement, fueled in part by the rise of opiate deaths in the districts of virtually every legislator in the state, to pass the criminal justice reform package earlier this year that progressive legislators had fought years to enact.

On issues not backed by large state-wide constituencies, such as expanding solar energy, the state legislature doesn’t move. California passed a law in 2015 requiring utilities to source half of their electricity from renewable energy. The Massachusetts House blocked a measure in 2016 to increase the share of renewables local utilities are required to use.

Anti-establishment

State Rep. Russell Holmes, who represents the 6th Suffolk District, says the challenges to longtime incumbents may be aimed at legislative leadership, noting that three of the four Boston reps facing challenges are members of DeLeo’s leadership team. Sanchez is chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, Malia is assistant vice chair and Rushing serves as majority whip.

“I think it’s more a reaction against the establishment,” Holmes said. “People feel like the building is being held up by the leadership. Even though the speaker has done some pretty progressive things, the Senate is so much more progressive. People see the speaker as the establishment.”

Powers agrees, saying that many of those challenging long-term incumbents are spurred on by frustration at the slow pace of change.

“If you’re not willing to take on these big issues, people are willing to get rid of you,” he said. “We’re seeing this across the state. In all these districts with conservative Democrats, we’re seeing challengers.”

He points to Jim Hawkins, an Attleboro Democrat who won an upset victory against a Republican city councilor in a special election for the Second Bristol District seat, and Mike Connolly, a Cambridge progressive who bumped longtime incumbent Timothy Toomey Jr. from the 26th Middlesex District.

Hawkins’ victory ought to be of particular interest to Republicans, notes John Walsh. The same dynamics that played out in Attleboro could propel a Democrat into the governor’s office come November.

“Hawkins was elected because of a surge of Democratic voters,” Walsh said. “That’s what keeps Baker’s team awake at night. That’s why they think they need to raise $30 million for his re-election.”

So far, the winds of change needn’t keep Holmes up at night. He has no challengers this year. But the challengers have him thinking.

“The city has changed a lot in the last 20 years,” he says. “The folks who are running are more representative of the people in the city. I wonder when my shelf life ends as well.”