This Thursday, Epicenter Community convenes a talk and reflection on a dramatic point in local history — the late-1980s effort by some in Boston’s black communities to detach their neighborhoods from Boston and form a new city. The idea was formally posed in 1986, in the form of a nonbinding ballot question. Despite the fact that it was intended to gauge the sentiments of residents in the proposed neighborhoods and would not of itself create a new city, the measure nonetheless was fiercely opposed by then-Mayor Raymond Flynn.

What: “Roxbury Love: Reflecting on Mandela, MA with Curtis Davis”

Where: Thursday Sept. 14, 6-9 p.m.

When: Hawthorne Youth and Community Center at 9 Fulda Street Boston, MA 02119

More information, visit: http://ow.ly/o6rV30f4LNX

“It’s a great grassroots campaign story,” said Malia Lazu, president of Epicenter Community. “The campaign reads like a Who’s Who of Roxbury history, from Mel King to Byron Rushing to Sarah-Anne Shaw.”

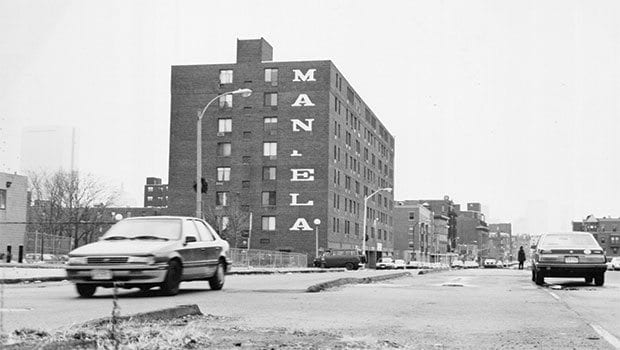

The envisioned new city, originally dubbed the Greater Roxbury Incorporation Project and later retitled “Mandela,” was intended to include Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, Jamaica Plain, the South End and Columbia Point. Encompassing 12.5 square miles, Mandela would have carved out one-quarter of Boston’s land, taking with it one-quarter of Boston’s population — and an estimated 90 to 98 percent of its black residents.

Andrew Jones, co-leader of the campaign, said at the time that the needs of black neighborhoods were not being met under the white governance of Boston. Inspired by other community self-determination movements, Jones said that the solution for these neighborhoods was self-government. Nationally, many newspapers regarded the vote as a referendum on the quality of the white-led city government’s service to black communities.

“We feel that we have a ‘colonial relationship’ with the city of Boston,” Jones reportedly said. “We feel that the city of Boston has treated us like second-class citizens and we’re fighting for basic rights of citizenship.”

The 1986 ballot question vote came just three years after Mel King became the first person of color to be a leading mayoral candidate in Boston. While he lost to Flynn, King was favored by more than 90 percent of the black voters.

“The black community elected a black mayor but didn’t have a city to put him in,” Jones told the paper.

Now in 2017, the city is due for its first black mayoral finalist since Mel King, and some are looking back to try to say what Mandela meant, and what it has achieved.

Divided communities

The Mandela plan was spearheaded by Jones, a violinist and television producer with a master’s degree in journalism from Boston University, and Harvard-educated architect Curtis Davis. With support from the likes of State Rep. Byron Rushing and then-State Rep. Gloria Fox, the campaign garnered the necessary signatures to bring a nonbinding question to ballot in the ten state representative districts that roughly encompassed Mandela’s proposed boundaries.

Opponents to municipal separation included the Flynn administration, along with black leaders and clergy such as Rev. Bruce Wall and Rev. Charles Stith, whose campaign adopted the moniker “One Boston.” Bruce Bolling, Boston’s first black City Council president, told The Boston Globe in November 1986 that he supported the referendum as a way to get feedback, but opposed secession.

The 1968 measure was defeated nearly 3-1. The night of the election, Flynn, Stith and Bolling released a celebratory statement, stating, “They [the people of Boston] have rejected the divisiveness of the past and have embraced unity. The secession proposal was counterproductive and polarizing in its attempt to divide Boston.”

Two years later, supporters successfully put the issue on the ballot, once again. The 1986 initiative was spurred largely by economic inequality, among other issues. In 1979, the average per capita income in Roxbury was less than two-thirds the average for Boston as a whole, according to a 2016 Trotter Review report by Zebulon Miletsky and Tomás González. In 1988, two years after the original bid, Jones told the Globe that service issues afflicting the neighborhoods remained inadequate, including what he said was failure of police to prioritize crime in those areas. Former City Councilor Chuck Turner told Trotter report authors at the time that the push also was driven by fears of gentrification and awareness of the high amounts of vacant, developable land in Roxbury and Dorchester.

After the ballot question was defeated for a second time, the effort was dropped.

What stopped Mandela, MA?

The Mandela bid ran head on into issues of practicality, organization-building and shifting circumstances. The Flynn administration insisted that Mandela would incur steep debt, and advocates were not able to dispel concerns that a new city would not be economically feasible.

According to Rep. Rushing, an early participant in Mandela discussions, Jones drew attention to the issue with strong charisma and communication skills, but failed to establish an organization that would continue to lobby and secure ballot status again and again, once its founding members departed. The organization never could secure binding action on establishing the municipality.

Organizers also may have sent the wrong message by holding their planning meetings at the Harvard Faculty Club, rather than at residents’ homes in Roxbury — something Jones later acknowledged was a mistake, according to former Banner writer and managing editor Brian Wright O’Connor. Davis said the faculty club was chosen in order to lend seriousness and credibility to the idea in its early days, according to the Trotter report.

Legacy

Rushing told the Banner that the Mandela initiative advanced a new kind of thinking.

“The main thing that came out of it was the community beginning to organize in different ways and see that there were radical possibilities for solutions,” Rushing said. “It did get a lot of black people and white people to think about new ways of political organizing.”

Trotter report authors also assert that the campaign encouraged Mayor Flynn to grant eminent domain powers to Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, an idea made more palatable when compared to the Mandel movement’s goal of having community control over far more land.

Epicenter president Lazu said that the campaign raised ideas that continue to be relevant.

“Roxbury decided it was going to explore its autonomy and power of self-determination, and it did that really well,” she said. “Roxbury may be at a time where it needs to once again circle up and think about autonomy and how to move forward to protect the people of Roxbury. We hope [the event] shines a light on some new ideas and new ways for us to think about protecting our neighborhood.”