In the opening scene of the searing Huntington Theatre Company production of the Suzan-Lori Parks play, “Topdog/Underdog,” Booth, a young black man, is practicing his skills at the street-hustling game of three-card Monte.

“Watch me close watch me close now,” Booth chants in the fast, singsong language of the game.

On the web

The Huntington Theatre Company’s production of “Topdog/Underdog” is on stage through April 9 at the Avenue of the Arts/BU Theatre. For more information and for tickets, visit: www.huntingtontheatre.org/season/2016-2017/topdog-underdog

With mounting ecstasy, Booth imagines himself as a master player. He spreads his arms upward and, standing in pulsing light, resembles a high priest. His makeshift podium of milk crates becomes his altar and his singsong chant an incantation to summon power he cannot find within himself.

In her brilliant Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Parks creates two characters that have been dealt a poor hand. She turns three-card Monte into a metaphor for the struggle of Booth and his older brother, Lincoln, for power and self-esteem. It is a win-or-lose game that the men wage against each other and themselves.

Rich with paradox

Her play is rich in metaphors, starting with the ironic names of the brothers, namesakes of John Wilkes Booth, actor and assassin, and his victim, President Abraham Lincoln, who led the country out of the Civil War and ended its era of slavery.

Their drunken father gave them the names as a joke. Their parents deserted them as youngsters, leaving each boy a wad of cash — $500. Lincoln has spent his money but Booth hoards his in his mother’s tightly-knotted stocking as a nest egg for his future.

On stage through April 9 at the Avenue of the Arts/BU Theatre, the riveting Huntington production capitalizes on the playwright’s own arsenal of sleight-of-hand tricks. Rich in theatrical wiles, the production, like the play, delivers tough truths under the guise of terrific entertainment.

A MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient, Parks is a dramatist whose plays explore the legacy of slavery as well as the fundamentals of human nature. Her characters often are shackled to a painful past and they may or not rise above their worst impulses.

In “Topdog/Underdog,” Parks creates a set of paradoxes. The play is both street-smart comedy and taut drama. Drawing from medieval allegorical plays, its two characters bear symbolic names and roles, but they are also fully fleshed out characters.

Tony, Grammy, and Drama Desk Award winner Billy Porter directs the Huntington production, with sets and costumes by Clint Ramos and lighting

by Driscoll Otto, the same team he worked with when directing the Huntington’s 2015 delirious and scathing production of George C. Wolfe’s play, “The Colored Museum.”

Wolfe directed the 2001 Off-Broadway premier of “Topdog/Underdog” at the Public Theater as well as its Broadway debut the following year, which won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Ominous and edgy

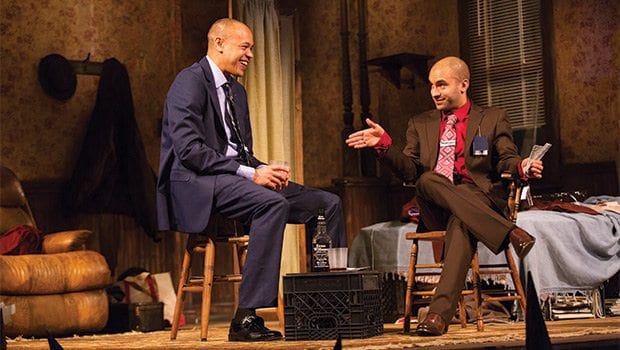

The Huntington staging of “Topdog/Underdog” is first-rate, rising to the challenges of a play that combines harrowing bleakness with gut-level humor, demanding intense vocal, physical and emotional gymnastics from its two-member cast. Matthew J. Harris (Booth) and Tyrone Mitchell Henderson (Lincoln) turn in heroic performances as two very different siblings who share a painful past.

The production runs over a fast-moving two hours and 20 minutes, with intermission.

Unfolding over a series of evenings in Booth’s apartment, the play begins as comedy despite ominous undercurrents. But as the hopes of Booth and Lincoln are thwarted, events take a darker turn.

Mounted on a large cube jutting out from the stage, the apartment is surrounded by jagged, metallic-looking spikes that suggest the flames of hell. This edgy geometric structure frames a vintage apartment with an ornate embossed ceiling and peeling, water-stained wallpaper. Furnishings consist of a bed and a recliner along with two milk cartons and a sheet of cardboard — tools of the card shark’s trade, here repurposed as a dining table.

Lucky break

Lincoln is the “topdog” brother although his wife has kicked him out and, with no place to go, he stays with Booth and sleeps on the recliner. A master of three-card Monte, Lincoln quit the business after his friend and fellow con artist Lonny was shot on the job. Now he works as an impersonator of Abraham Lincoln. Wearing white face and period attire, he sits in a shooting gallery and as customers re-enact Booth’s assassination by shooting at him with a fake pistol, he drops dead.

In his fake beard, black top hat and frock coat, Lincoln looks like a gloomy clown. But he considers the job his first lucky break in a long time.

Returning to the apartment in his costume after a day at the arcade, Lincoln startles Booth, who pulls out his gun, a real one.

After they settle down, Lincoln tells Booth of another lucky break. While he was on the bus, a child who believed he was seeing Lincoln asked for his autograph. Sizing the boy up as a rich white kid, he agreed to sign his book for $10. The boy only had a $20, and, as “Honest Abe,” he promised to give him the change the next day. The brothers laugh at that. Lincoln spent his windfall at Lucky’s, a local bar.

Like the president he impersonates, Henderson has a tall and thin physique. His Lincoln is soft-spoken, even while trading taunts with Booth. But when he wakes up from a nightmare, reliving his addiction to the game and its violence, Henderson shows his character’s anguish and fear. Later, with equal dexterity, Henderson renders Lincoln’s chameleon-like change into a slick, fast-talking hustler who wears his stylish fedora at a jaunty angle.

Brotherly rapport

Harris has an athletic build and he endows Booth with seething physicality and emotional energy. He summons Lincoln for their weekly budget session and conducts it with the rhythm of a card game, snapping dollar bills down in separate piles for rent, electricity and a phone. When Lincoln says “We ain’t got no phone,” Booth replies, “We pay our bill — they’ll turn it back on.”

Booth is a manager. A homemaker. He is also a nimble shoplifter. He could be a provider. But he has trouble holding a job. Booth wants his brother to quit the arcade and return to the big money of the card game, with him taking the place of Lincoln’s dead friend.

Lincoln is exhausted by life and likes his sit-down job. Booth is a go-getter, determined to win back his former girlfriend, Grace.

Henderson and Harris convey the tough and tender rapport between the brothers, whose banter includes recollections of their parents. Sharing a take-out Chinese meal over the milk crates, they recall “gathering around the table” as a family. With bitter humor, they soon puncture these daydreams with tales of their raunchy father.

Waiting in vain

Complemented by artful staging, including deft lighting and costumes, the actors create arresting stage pictures. A shadow of Lincoln in top hat conjures a period silhouette of the president. Freeze-frame scenes show their characters’ inner worlds. Attired in tasteful suits shoplifted by Booth, the men pose in an image of aspiration that eludes them in real life. As Booth says, “Clothes make the man.”

Later, nattily suited and awaiting his girlfriend, Booth stands motionless before his transformed apartment, its crates covered by fine linens and silverware. His hardened face lets on that he is waiting in vain for Grace.