Dr. Michael Groff is the director of the Neurosurgical Spine Service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. Yet, he is not that eager to put someone under the knife for low back pain. “Seventy to 80 percent of the people get better with physical therapy,” he explained. “You should see improvement in the first four weeks.” However, if at six weeks there is no improvement or the pain is worsening, a different course of action is needed. “At this point the likelihood of getting better [with conservative therapy] is less than 20 percent,” he said.

Author: Brigham and Women’s HospitalDr. Michael Groff, director of the Neurosurgical Spine Service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital.

He asks a series of questions to determine if a person is a candidate for surgery. Is the pain confined to your back, or does it spread to your buttocks and down the leg he wants to know. Have you tried more conservative treatment, such as physical therapy for at least six weeks? Is the pain the same, or has it gotten worse? Are there activities of daily living you can no longer do?

In some cases actions speak louder than words. Those afflicted are sometimes easy to spot. “They can barely take a step,” he said.

Very few patients with LBP need to resort to surgery. Only about 5 percent are good candidates, according to a white paper published by Johns Hopkins Medicine. Groff agrees with that. For him it’s a combination of the story and the results of imaging tests, which can identify a structural cause for the pain. If the two are in sync, surgery is a good bet. The severity of the pain is not always correlated to the need for surgery.

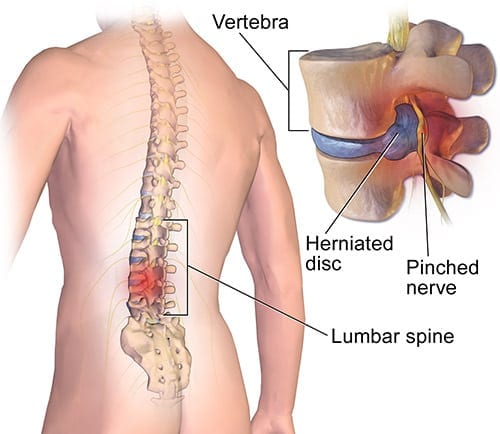

Some spine conditions tend to respond to surgery more than others. Herniated discs occur when the inner gel of the disc oozes out and hits a spinal nerve. The radiating pain down the leg is a telltale sign. In spinal stenosis, the open area of the spine that houses the spinal cord is compromised, again leading to pain.

Surgery for LBP has made huge strides since the 1990s. Traditional open surgery required a six-inch incision and retraction, or pulling of the attached muscles in order to allow a better view of the problem. This technique, however, affected more anatomy than the surgeon required, and increased the potential of muscle injury and pain.

LBP can often now be treated with minimally invasive surgery. The half-foot incision has been whittled down to an inch or two, while still allowing the surgeon good access to the spine. The instruments as well as the technique have improved. “We have better microscopes and a better understanding of the goals of surgery,” Groff said.

The outcomes of the two approaches are similar. However, the recovery from MIS is easier. Those treated for a herniated disc can return to work in about two weeks. Those who had spinal fusion, a procedure designed to inhibit movement in a painful vertebral segment, require four weeks to heal and a possible stint of physical therapy, according to Groff.

There are some instances where surgery is indicated as the first line of treatment. Profound weakness in the foot is one of them. Abnormality of urinary function is another. “You don’t have the luxury of time,” Groff said.

Not all low back conditions can be treated with MIS. If the deformity is too advanced or the pathology of the spine too complicated, traditional open surgery is probably better.

The goal of MIS is to “achieve the same surgical objective as open surgery with less trauma.” Groff’s philosophy is to do the least possible for the most benefit. “Actually the surgery you don’t do is the best MIS,” he explained.