Italian renaissance books on display at Gardner Museum through January 16

A book can provide a close-up, personal dose of enchantment. Books that combine words and pictures have a special allure. And if they come from another time, they offer a magic carpet ride into another world that may not be so unlike our own.

Author: Photo: Courtesy Harvard Divinity School, Andover Theological Library“St. Mark” from a copy of The Four Gospels, Sanahin Monastery, Lori Province, Armenia, 1504.

The appetite for telling stories in picture books may begin with children’s stories but plenty of grown-up artists remain entranced, publishing graphic novels and reviving the painstaking craft of hand-made books.

An encounter with such books from 1,000 years ago awaits visitors to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum through Jan. 16, in the exhibition “Beyond Words: Italian Renaissance Books.”

Viewing a selection of Renaissance-era picture books is a special pleasure at the Gardner, a 15th-century Venetian palazzo on the Fenway with a fragrant courtyard garden and a collection of Renaissance masterpieces on the walls as well in display cases.

The palazzo and its holdings are the personal creation of Isabella Stewart Gardner. She was among the Boston Brahmins whose avid collecting during the 19th century has made Greater Boston colleges, universities and libraries the largest center of Renaissance artworks outside of Europe.

Collaborative exhibition

The Gardner is one of three local institutions to host a collaborative exhibition, 16 years in the making, entitled “Beyond Words: Illuminated Manuscripts in Boston Collections.” During the three-month exhibition, the Gardner, Harvard’s Houghton Library and Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art, have displayed a total of 260 painted and printed books at their respective sites. Dating from the 8th to 17th centuries, the works were loaned by 16 neighboring institutions, including the Boston Public Library, Wellesley College and the Museum of Fine Arts. A catalog with contributions by 85 scholars accompanies the three simultaneous exhibitions.

Although the installations at the Houghton Library and McMullen Museum closed last week, a web site (http://beyondwords2016.org) will keep this landmark collaboration alive for years to come.

Curated by Anne-Marie Eze, the Gardner exhibition traces the collaboration of Italian humanists and learned clergy in the propagation of books.

Civilization was under siege in the Middle Ages, as the region that was to become Europe was wracked by plagues and invading hordes. Countless scribes in monasteries and convents kept learning alive by copying and illustrating books — the Bible as well as classics of Greek and Roman antiquity — that were to become touchstones of learning, culture and civil society in that era of peace and prosperity within Europe known as the Renaissance.

A sensory experience

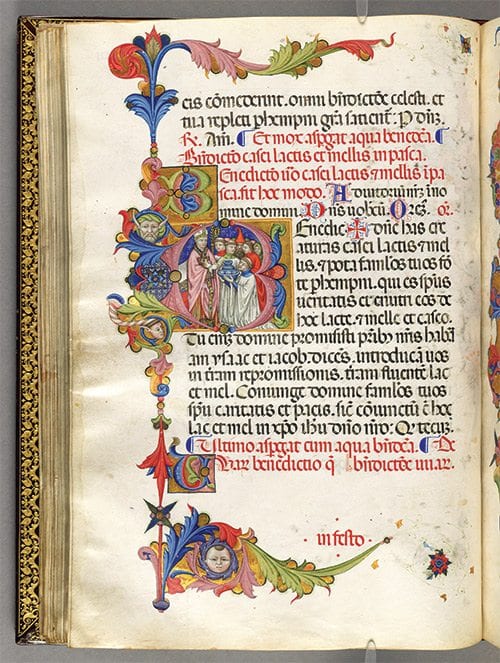

Writing in quill pens crafted from birds’ wings, with inks ground from plants and minerals on parchments made from animal hides, scribes would then illuminate their pictures and lettering by breathing on stencils hand-cut from sheets of precious metal such as gold leaf. Ivory and gemstones also added glory to Bibles large and small, encrusting the pages with jewel-like embellishments as shimmering as Tiffany lamps.

Mingling pictures of saints and illustrations of parables with earthly images of foliage, fruit, mythical beasts, apes, peacocks and children at play, they created books of worship that Roger S. Wieck describes in the catalog as “a private picture gallery to please the eye and inspire the heart.”

Crafting and reading these books were sensory experiences. Reading was not a silent exercise, exhibition co-curator Jeffrey F. Hamburger writes in the catalog. “Especially in the early Middle Ages,” Hamburger writes, “reading was spoken or at least mumbled and at times even sung. Monastic manuals compared the process of reading to the mastication and rumination of animals, which sought to extract spiritual nourishment from the text.”

Jumbo Bibles served public worship and for personal prayers throughout the day, and a well-off patron would enjoy a personal prayer book, known as a “book of hours.” During the 300-year peak of the handmade book examined in “Beyond Words,” from 1250 to 1350, such volumes were best-sellers.

The exhibits

Focusing on the Humanist Library, the Gardner exhibition opens with a replica of a “studiolo,” a scholar’s private chamber, complete with a tapestry-covered period desk and early Roman statuary. A 1482 painting shows Saint Jerome in a similar study, translating the Bible from Hebrew into Latin. On an adjacent wall are other items from the Gardner collection, including portraits of the era’s prominent men and women and a display case of correspondence from writers who include a pope, a book merchant and a poet.

Inside the gallery, a display shows a large image of the church-like interior of a renowned Florentine library of the era, where books were chained in place and patrons switched seats to access their chosen volumes.

Among the gilded and colorful handmade books are four massive Bibles and a beguiling array of books of hours from Naples and Venice. Several prize Gardner holdings show the shift to black-and-white illustrations and typefaces with the advent of the printing press in the late 1460s. These works include a 1481 edition of Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” printed in Florence and illustrated by Sandro Botticelli. The volume is open to a scene in the Inferno.

Nearby is Gardner’s 1502 edition of Dante’s masterpiece, printed by Aldus Manutius of Venice. Thanks to his genius as a designer, printer and entrepreneur, Venice soon surpassed Florence as a publishing center. Prominently displayed is the trademark of Manutius, an early defender of intellectual property, who patented his elegant designs.

Digital technology opens a new chapter in the story of books, and on Thursday, Jan. 12, at 7 p.m., the Gardner will host Anthony W. Marx, president of the New York Public Library, for a talk entitled “Beyond Gutenberg: Access in the 21st Century.”

Although the Gardner’s partner institutions closed their exhibitions last week, each one contributed compelling segments to “Beyond Words.” The McMullen inaugurated its new quarters, a Renaissance Revival palazzo, with its exhibition, “Manuscripts for Pleasure & Piety.” Galleries on two floors presented 180 illuminations dating from the 11th to the 16th century. Arranged in columns within rows of display cases, the open books resembled a legion of butterflies at rest.

Memorable objects included an eight-foot parchment from 1200 showing the family tree of Jesus, starting with Eve, apple in hand; and a 35-foot-long scroll from 1470 tracing milestones of biblical and human history from the Creation to the present day.

Secular volumes included a manual with fine drawings on the care of humans and horses. A silk-bound physician’s diagnostic guide, folded up, is no bigger than a smart phone. A female author’s book instructs women on taking moral and economic leadership within their households. Its illustrations include a mini-drama showing the author still exhorting her readers from her sickbed while being attended by female allegorical figures of rectitude, justice and reason.

Monastic images

At Houghton Library, the exhibition entitled “Manuscripts from Church & Cloister” presented exquisite examples of monastic craftsmanship in works of formal grandeur as well as private devotion.

A magnificent text to accompany the Mass illustrated the priest’s prayers with ornate gilding that extends to the accompanying hymn. The musical notes, appearing as gilded flecks, are abstract expressions of joy. In a small Bible, a passage announcing the Resurrection showed an athletic-looking Christ climbing out of his tomb.

Among the most endearing images in the entire exhibition is a tiny illustration of the evangelist Mark painted in 1504 at an Armenian monastery. The serene composition of streamlined curves and rectangles is rendered in warm tones of red, green, blue and yellow. A starry sky behind him, Mark sits at his desk, his hand resting on a blank page. Overhead, as a divine hand extends from the clouds and streams down a band of inspiration, Mark’s eyes are wide open in wonder.