In September last year, former state Rep. Mel King picked up a copy of the Banner and saw in a front-page photo an image of his 1981 book, “Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development,” prominently displayed by a young activist who was speaking out against the Boston Police Department’s treatment of young blacks and Latinos.

That front-page photograph set off a chain of events that one year later led to the 35-year-old book being republished with a new epilogue, “Future Links in the Chain of Change,” written by King, Alex Ponte-Capellan, and fellow members of the organization Young Abolitionists.

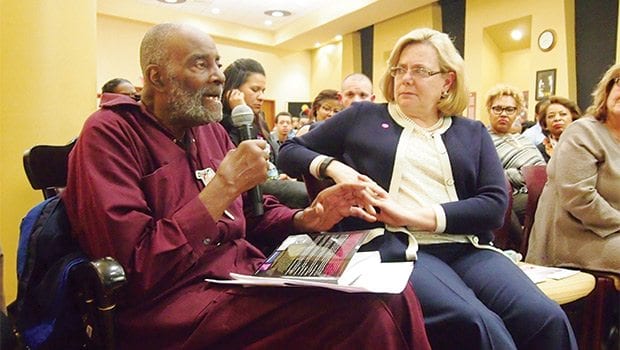

Young Abolitionist member Alex Ponte-Capellan was photographed holding ‘Chain of Change’ in this September, 2015 photograph.

“‘Chain of Change’ is a beacon through the haze of history, allowing us to finally connect dots that were for so long obscured for us,” the Young Abolitionists write. “In reading, we found that successful mass mobilizations were not restricted to other parts of the country, as decades of persistent, and many successful, examples of community organizing stood right here in our own neighborhoods.”

King’s book chronicles his life as an activist — from the 1950s, when he witnessed the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s urban renewal program leveling the New York Streets section of the South End where he grew up, through his historic 1983 campaign for mayor, during which his Rainbow Coalition created a model for the black, Latino, Asian and progressive white alliances that have become a dominant force in Boston politics.

While several books have written about the 1960s and ’70s in Boston, most, like J. Anthony Lukas’ “Common Ground” or Larry Harmon and Hillel Levine’s “The Destruction of an American Jewish Community” were written from a white perspective. King’s work as a former state legislator afforded him an insider’s perspective on the issues and events that shaped Boston’s social and political life. In his chapter “Court-Ordered Desegregation,” King counters the notion that blacks pursued desegregation as an end in itself, recounting blacks’ struggles to secure equal resources for students, control over school curriculum and teaching jobs for people of color over the objections of the all-white Boston School Committee.

On the subject of the 1967 Grove Hall Riots, King quotes veteran organizer Chuck Turner who countered the narrative that blacks caused the melee.

“When the Banner talked about a ‘Police Riot’ it pulled to covers off the police and everybody had to look at the reality,” Turner is quoted.

A new perspective

For the Young Abolitionists, the book represented a window to a past that none had heard of.

“We were trying to learn more about what activism had happened in Boston to inform the work we we’re doing,” said Armani White, a member of the group, which began organizing around police abuse, the school to prison pipeline and other social justice issues in 2012. “You hear a lot about Malcom and Martin, but you never hear about what happened here.”

White came across King’s book after searching “black Boston history” on Google. He shared the book with other members of the group.

“We were inspired by what we read,” he said.

When Ponte-Capellan met a Banner reporter last year for a story on the difficulties faced by teens erroneously placed on the Police Department’s gang list, he insisted on being photographed with “Chain of Change” in his hand.

King said the photograph reminded him of his original inspiration to write the book.

“The reason I wrote it was so that the youth would see what we’ve tried to accomplish and what we were able to accomplish,” he said.

King contacted the Banner and obtained Ponte-Capellan’s phone number. He then invited the Young Abolitionists to meet with him.

“I asked them to talk about what the book meant to them. I had them put their thoughts and ideas into the book.”

King secured funding from Eastern Bank for the 1,000-copy reprint, which was done through Boston-based Hugs Press.

In the 1981 edition, King included an epilogue that featured interviews with 16 community activists including Paul Parks, Melnea Cass and Archie Williams. In 2016, King interviewed the four surviving activists — state Rep. Byron Rushing, Turner, former journalist Sarah-Ann Shaw and former Roxbury Action Program director George Morrison — and appended their interviews to the epilogue.

But for King, it’s the four pages from the Young Abolitionists that stood out the most.

“Seeing that picture and having them do this article has been one of the most moving moments in my life and work,” King said. “It’s what the book was written to do.”