Football players risked athletic careers for civil rights in college, now tell their story

In the spring of 1970, nine black college football players — including several who were up for NFL recruitment — put their athletic and academic careers on the line to protest what they said was racial discrimination and insufficient medical care for all athletes. For many of these Syracuse University students — dubbed the “Syracuse 8” (media at the time was unaware that a ninth, injured player was involved) — their decision to boycott spring practice brought an end to their football careers. It also brought a ticket into civil rights history.

If you go

What: Book signing and discussion

Where: Museum of African American History, 46 Joy St, Boston

When: Friday October 28, 5 p.m.-8 p.m.

Tickets and more information: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/leveling-the-playing-field-reception-book-signing-w-the-syracuse-8-tickets-28124414882

Five members of the Syracuse 8 will reunite in Boston this Friday, 47 years later, for a signing and discussion of a book published last year that tells their story.

Local members of the Syracuse 8, Cambridge-and-Boston-raised Alif Muhammad (known at the time as Al Newton) and Dana Harrell, who moved to Boston in the ‘80s, recently recounted their experiences during an interview at the Banner office.

“For a period of time after you take a stand and are [off the field] watching guys you played with and against play, you squirm,” Harrell recalled. “But if had to do it again, I would do it the same damn way.”

The Syracuse University students’ allegations of racial discrimination were vindicated in a human rights investigation conducted by the state. Thirty-six years after the protest, the university officially apologized.

Muhammad said he sees the Syracuse 8’s decision to boycott as a continuation of a movement that includes activists such as John Carlos, who, after winning an Olympic bronze in track and field in 1968, raised his fist in the Black Power salute during the national anthem. Today, Black Lives Matter members, Colin Kaepernick and other proponents of racial justice seem to be taking up the mantle, Harrell said.

“Young people finally again decided to make decisions about what’s important to them,” he said.

The Syracuse boycott

The Syracuse 8 directed their protest to four goals: equal access to academic tutoring for black players, improved health care (operations on the wrong limb were not unheard of, Muhammad said), merit-based allocations of playing time and racial integration of the coaching staff.

In the late 1960s, the players filed a complaint with the New York state Human Rights Commission. Following what they claimed was the university’s failure to uphold its promise to diversify the coaching staff, they boycotted the spring 1970 practice and presented the football coach and university chancellor with their list of four demands.

The chancellor and coach discussed the proposed reforms with the players, but when the Syracuse 8 refused to sign a statement blaming them for the conflict, they were suspended from the 1970 football season.

Tensions built. Supporters of the Syracuse 8 protested in solidarity at the season’s opening game, and NFL player and Syracuse alum Jim Brown tried to facilitate negotiations. Meanwhile, white players threatened to walk out if the black players were allowed to return. Harrell said the white players fell into three camps — those who sympathized with the cause but disagreed with the decision to appeal to authorities other than the football coach, those who did not care about the issues and just wanted to play, and those who hated blacks.

In December 1970, the New York Human Rights Commission concluded its investigation and reported that there was longstanding racism in Syracuse’s athletic department.

Decision to boycott

Many of the Syracuse 8 were 19 and 20 years old when they chose to boycott, Harrell and Muhammad recounted.

“We were the generation where we were no longer just happy to be there [on campus],” Harrell said. “We were the change generation.”

Taking a stand meant giving up a shot for professional football careers. Three of the Syracuse 8 were up for recruitment by the NFL, Muhammad said.

“We were going for national championship that year,” Muhammad said. “We had a powerhouse team.”

Even more worrisome: many were first-generation college students relying on scholarships that they feared could be revoked. Each player made an individual decision on whether to join the protest, with two deciding the sacrifice was more than they could risk. In the end, nine agreed to boycott: Greg Allen, Richard Bulls, John Godbolt, John Lobon, Clarence “Bucky” McGill, Duane Walker, Ron Womack, Harrell and Muhammad.

Muhammad said some of his family agreed he had to take the stand he believed in, while others feared he was throwing away opportunities. Harrell’s father called him and made him promise that no matter what happened, he would get a college degree.

“‘When you’re 40 years old, you’ll need that college education,’” Harrell recalls his father told him.

Several graduate students advised the Syracuse 8 to pare their grievances down to a few fundamental concerns and proposed solutions, which Harrell said were key.

Today’s athlete-activists

Harrell and Muhammad praised Colin Kaepernick, whom Harrell said is one example of how this generation’s youth are taking action on what matters to them.

When the 49ers quarterback protested police brutality against people of color by not standing during the national anthem, he sparked praise, imitation and fierce backlash, including some claims that he was un-American.

Like the Syracuse 8, Kaepernick decided that civil rights was more significant to him than football, Harrell said, and lauded him for expressing his message peacefully in the most visible way he could.

“The things they’re saying about him is what they said about us … we were ‘ungrateful’, ‘disrespectful’ … and those were the nice comments,” Harrell said.

Life without football

After being kicked off the team, most of the Syracuse 8 never played for Syracuse again, and the NFL blackballed them, Muhammad said. Being locked out of sports forced them to discover new talents, Harrell recalled. After graduating from college, four of the Syracuse 8 went on to attain master’s degrees, with two earning doctorates.

Muhammad, now retired, is an instructional coach in education for the state’s juvenile justice system; he also has served as an adjunct professor at Springfield College.

Dana Harrell now is an attorney and principal of Harrell Associates real estate consulting firm, and formerly served as deputy commissioner of real estate services in former Governor Deval Patrick’s administration.

Reconciliation

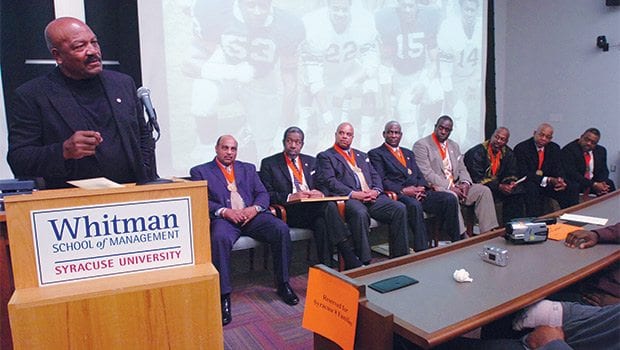

In later years, many white players reached out to apologize, including one whom Harrell described as “one of the most virulent racists at the time.” In 2005, the Syracuse 8 were invited to tell their story at Syracuse’s African American and Latino alumni celebration. Their talk inspired the chancellor to award them the university’s highest honor, the Chancellor’s Medal, for courage give them the letterman jackets they never received. The event also attracted writer David Marc to their story, and he spent the next eight years working on a book, which published in 2015.

Earlier this month, Syracuse 8 members answered an invitation to speak about leadership and their protest with schoolchildren in Richmond, Virginia. Muhammad said it was striking to be invited to the former capital of the Confederacy, and that he hopes the Syracuse 8’s story helps inspire the next generation to take a stand.

“Hopefully there will be a new set of leaders coming out of that,” Muhammad said.