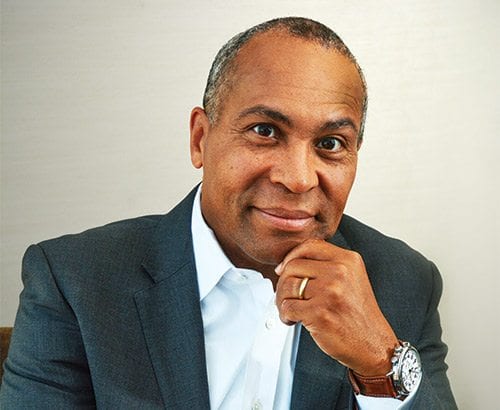

Deval Patrick says ‘It’s time for business to step up’

The former governor talks with Banner Biz about wealth disparity and his current work to close the gap.

Former Massachusetts Gov. Deval L. Patrick’s remarkable rise in law, business and politics in the Bay State began over 40 years ago when he arrived by bus from the South Side of Chicago to attend Milton Academy as a full scholarship student. Going on to Harvard College and Harvard Law School, he became a prominent attorney, ran the Civil Rights Division in the U.S. Justice Department under President Clinton and served as general counsel of Texaco and Coca-Cola before launching an unheralded run for governor in 2006.

In spite of low name recognition, no background in electoral politics and a disadvantage in fundraising, Patrick defied expectations to defeat better-known opponents, including the sitting Republican lieutenant governor, to become the first African American governor in Massachusetts history. Many of the themes of his “Together We Can” campaign appeared two years later in the race for the White House by Barack Obama. Patrick’s leadership helped Massachusetts fare better than any other state during the 2008 economic downturn. He easily won re-election in 2010.

After leaving office, he joined Bain Capital to focus on social impact investments as an innovative approach to stubborn public policy issues. Bain’s Double Impact Fund concentrates on three core themes to create long-term value: sustainability, health and wellness, and community building.

Patrick’s inspiring life story, chronicled in his autobiography, “A Reason to Believe: Lessons from An Improbable Life,” still has unwritten chapters. The former governor talks with Banner Biz about wealth disparity and his current work to close the gap.

Author: Don West“There are big social and environmental challenges that face us: food scarcity or climate change or job creation with livable wages, for example. Government and not-for-profits can’t solve those issues on their own. Business has a role.”

On the web

Bain Capital: https://www.baincapital.com

You are recognized as a very effective two-term governor of Massachusetts. During your time in office, the issue of income inequality was not as prominent as it is today. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston recently published a report entitled “The Color of Wealth in Boston” that claimed the wealth in Boston of nonwhite households is essentially negligible compared with a median wealth of $247,500 for whites. What programs did you initiate at that time to address the wealth gap?

First, we have to acknowledge that the wealth gap is real, and it derives from historic choices that are real and intentional — choices like where African Americans could live or build businesses, to whom they could sell, whether they could gain access to capital, and the like. Many of those barriers have been eliminated by law. Some persist in effect. The Great Recession made things worse.

To me, the fundamental challenge is not exactly income inequality, in the sense that we have always had rich and poor. The problem is economic mobility, in the sense that it feels harder than ever to lift yourself out of poverty and into the middle class. And while Massachusetts climbed out of recession faster than most other states, some of the impact of it lingers. Home values — the principal means by which most Americans have created wealth for generations — are only just beginning to rebound. And an awful lot of African Americans got caught up in the mortgage crisis, saddled with unaffordable debt and houses they could not sell, with all that does to undermine credit history. And many who lost jobs during the recession are unlikely to return to the jobs they once had.

I still believe education — pre-K through higher ed and workforce training — is key, and I’m proud of the work we did there. We invested in the public schools at record levels, even when the bottom was falling out of everything else, and the Achievement Gap Act brought a new era in education innovation. Student achievement led the nation for the last six several years we were in office, and achievement gaps based on race and ethnicity began to close. That will matter over time.

We built international excellence in the life sciences and clean energy industries in particular, and many of the resulting jobs were for middle skills talent, not just for Ph.Ds. One of the fastest-growing sectors in our economy was advanced manufacturing, so much so that business leaders were having a hard time finding the talent they needed for entry level positions at $75,000 or more.

While in office, we expanded state purchasing programs so that they were more inclusive, including disaggregating large state procurement contracts to make it easier for small businesses to compete, through an office dedicated to such efforts. Candidly, I’d say we got modest results. Remember that we were in the midst of a global recession so it was not a time of marked growth in state buying power.

I will say that the private sector is where the action is in terms of large scale opportunities to build business and the wealth that comes from it, and it is still harder than it ought to be for entrepreneurs of color to break in. We left office with the state at a 25-year high in employment, and that’s good. But we need that economic expansion to reach out to the marginalized, not just up to the well-connected. There’s more work to do there.

In your opinion, what is the social impact of such wealth disparity and was it part of the impetus for you to focus on social impact investing?

Wealth disparity, like any disparity, is dispiriting. That matters when you consider that lifting yourself and your family demands an act of faith, a belief that there is opportunity of which to make the most.

We started Bain Capital Double Impact because I am convinced it’s possible both to do good and do well. More and more consumers are attracted to goods and services that stand for something, and more and more entrepreneurs are mission-driven — selling products or solutions that address food scarcity or energy efficiency or achievement gaps in the schools. Or just building companies that create good jobs in places of chronic underemployment. We want to be their capital partner when they are ready to scale.

Some of those concerned with social change assert that “social impact” investing will lead to progress. Social impact investing is a term broadly used with different strategies. Currently as Managing Director at Bain Capital you were hired to develop their Social Impact portfolio. What does the term mean to you and how does it direct your mission?

Impact investing means different things to different people. For us, it means being intentional about a company’s social and environmental bottom lines. The fact is every investment has impact. Today, at a time of ubiquitous information, good managers have to think about and manage for the risks of social and environmental actions. In my view, it’s not that big a leap from there to impact investing.

There are big social and environmental challenges that face us: food scarcity or climate change or job creation with livable wages, for example. Government and not-for-profits can’t solve those issues on their own. Business has a role. And when you consider that the solutions to some of those challenges will be products and services sold by private industry, you realize there is money to be made.

I think the other thing that motivates me is a sense that for a long time government and not-for-profits have been addressing some of the hardships caused by some of the short-term behaviors in private enterprise. It’s time for business to step up. I think that as we show that you don’t have to trade return for positive impact, it models better business approaches for others.

Will this role at Bain enable you to support minority-owned and managed firms to improve profits? What are a few of the extraordinary challenges that minority-owned businesses have had in the past that you believe can be remedied in the immediate future?

We’re focused on great businesses in North America that we can help to scale and where we can achieve both a competitive financial return on our investment and measureable impact in the areas of sustainability, health and wellness, and community building. Community building for us means investing in companies that are creating jobs and wealth in areas of chronic underemployment. Many minority entrepreneurs are doing just that. When they are ready to scale, we want to be their equity partner.

The challenges of minority-owned businesses are many, but they are not always unique. Getting credit, relying on suppliers, finding and retaining talent, staying ahead of the competition, expanding markets — every entrepreneur faces challenges like that. Minority entrepreneurs — like minority people in general — also deal with the concern whether ordinary challenges are made greater because of race. That’s a level of extra anxiety that weighs on a minority business owner, I suppose. I just hope we learn not to limit ourselves by low expectations, both the low expectations others have of us and those we sometimes have of ourselves. Dr. Benjamin Mays, the legendary president of Morehouse, famously and rightly said that “not failure, but low aim, is sin.”

Your past involvement in the corporate world was as a senior executive with Texaco and Coca-Cola, both Fortune 500 companies. How does that experience with the big corporations inform your advice to much smaller companies struggling to scale up and prosper?

I’ve served on the boards of, or as counsel to, small and medium-sized companies, too. They are different from big complex global companies, you’re right. For one thing, it’s harder to hide mistakes and misjudgments in small companies. And small companies have to, and can, adjust more quickly to market changes than big ones. These are advantages, in fact, especially in times where market conditions and opportunities change as quickly as they do nowadays. I want to bring the range of deep experience at Bain in building great companies to bear on mission-focused companies, and help them grow bigger and more successful.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about half of the newly established firms fail in the first five years and only one-third will survive for ten or more years. What would be your advice to young entrepreneurs who have decided to take the risks?

Stick to it and ask for help. Chances are there’s another entrepreneur trying to solve the same kind of problem you have been facing.