A Cape Verdean-English dictionary

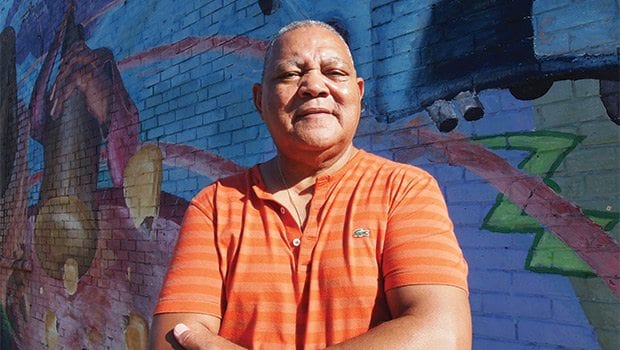

Dorchester man captures evolving language

Like many children who grew up in Cape Verde pre-independence, Manuel Da Luz Gonçalves was forbidden from speaking his native Creole language during school.

“Creole was not recognized as a language,” he says. “For us, to study Portuguese was mandatory. If you were caught speaking Creole on school grounds, you would be punished.”

After the island threw off the shackles of Portuguese colonialism in 1975, Gonçalves worked with other Cape Verdeans in Boston to write the curriculum for the Boston Public Schools’ first Creole-English bilingual program. In the 1990s, he worked with other linguists on efforts to standardize spelling in Cape Verdean Creole — efforts that led to ALUPEC, the phonetic alphabet now recognized by the Cape Verdean government.

Now, after ten years of researching word usage on the archipelago’s ten islands, Gonçalves, who lives in Dorchester, has completed the first-ever Creole-to-English dictionary. After wading through 220 books written in Creole and listening to innumerable recordings of Cape Verdean music, Gonçalves gathered more than 40,000 words for the dictionary, which was published in February.

Earlier efforts have yielded Creole-Portuguese and Creole- French dictionaries, Gonçalves’ dictionary is the first to open up the language to English-speakers.

“This is absolutely wonderful,” says state Sen. Vinny deMacedo, a Plymouth Republican who grew up speaking Creole at home, but never learned to read in the language. “I’m incredibly grateful for his persistence. I know I’m not the only one who will benefit from this.”

Slave history

The Cape Verde islands were uninhabited when they were settled by the Portuguese in the 15th century. The Portuguese used the islands as a transfer station in the trans-Atlantic slave trade until its decline in the 19th century. Many West Africans remained on the islands. Those Africans, many of whom mixed with the Portuguese, created the Cape Verdean Creole that is spoken today.

The language has a primarily Portuguese lexicon, with many African and some English words. While Creole is the universally-spoken language in the ten-island archipelago, most schools there still give instruction in Portuguese.

Because the language was effectively banned by the Portuguese, there is little that has been written in Creole before independence. Gonçalves says he leaned heavily on Cape Verdean folklore and music to glean words and shades of meaning. In those stories, many of which Gonçalves heard growing up, he gained not only a deeper understanding of his native tongue, but also a greater appreciation for Cape Verdean culture.

“You always listened to these stories in the evenings,” he said. “They were never written down. Hearing them was like traveling back into time.”

While there are 525,000 people living in Cape Verde, there are an estimated 265,000 people of Cape Verdean descent living in the United States, primarily in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Gonçalves says his dictionary will be useful to people taking Cape Verdean Creole classes at Bridgewater State College and University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, as well as U.S. citizens serving in the Peace Corps in Cape Verde.

He has gotten orders for his book from many local Cape Verdeans, as well as from people as far away as Norway, Finland, Austria and South Africa.

“I think there’s interest from a lot of people who work in linguistics and cultural anthropology,” he said.

Prior to the dictionary, Gonçalves published a Cape Verdean Creole grammar book called “Pa Nu Papia Kriolu” (“for us to speak Creole”). He moved to Boston in 1974, after he was conscripted into the Portuguese military. Gonçalves received a master’s degree in guidance and counseling and taught in Madison Park High School’s bilingual program.

Copies of Gonçalves’ dictionary can be purchased on his website: http://mili-mila.com. On Thursday, Sept. 1, the Consul General of Cape Verde will host a reception for Gonçalves at their local consulate at 300 Congress Street in Quincy at 6 p.m.