The idea of the north

The paintings of Lawren Harris are on display through June 12 at MFA

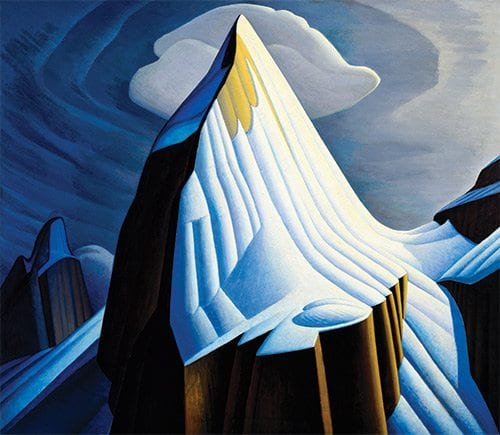

The allure of landscape paintings by Canadian artist Lawren Harris is their power to draw the viewer into the scene. Rendered in oil, his works bring viewers into a contemplative state, as if they were in the sublime setting that inspired the painting. Harris does this not by illustrating a place but instead, by distilling its essence.

Harris (1885-1970) sought out pared-down subjects, mainly in the Canadian north, a region coated in ice and snow and shorn of vegetation, but full of light and shadow, shapes and textures and dramatic interplays of sky, water and earth. With their immediacy and spare intensity, Harris’s landscapes of the Canadian north cast a spell.

Among those who are captivated by Harris’s paintings is comedian, actor, author and art collector Steve Martin, guest curator of “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris,” a riveting exhibition on view through June 12 in the Art of the Americas Wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA).

Organized in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the show presents 30 works by Harris from public and private collections. The exhibition debuted at the Hammer Museum in October 2015 and will open in July at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and remain on view during Canada’s 150th anniversary celebration in 2017.

Although Harris is renowned within Canada for works that exalt his country’s wilderness as core to its character, this show is the first major solo exhibition of Harris’s art in the U.S.

The exhibition focuses on Harris’s works from the ’20s and ’30s, when he focused on distilling the essence of Canada as well as the essence of a moment in nature. In a 1926 article, “Revelation of Art in Canada,” Harris wrote, “It seems that the top of this continent is a source of spiritual flow… and we Canadians being closest to this source seem destined to produce an art somewhat different from our southern fellows – an art more spacious, of a greater living quiet…”

Well-off and educated as an artist in Europe, Harris was a founding member of the Group of Seven, a Toronto-based collective of painters who shared his desire to develop a new artistic movement within their country.

This new-world impulse to distill the sublime in nature and develop an original vein of art independent of old-world Europe was shared by Harris’s kindred spirits to the south, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley and Charles Sheeler.

Capitalizing on its rich holdings in early U.S. modernism, the MFA accompanies the Harris exhibition with two adjacent galleries of works by Harris’s U.S. contemporaries. In their semi-abstract explorations of form in nature and industry, they share common ground.

In addition to organizing the Harris exhibition, Martin also curated one of these galleries, selecting about 20 works, many from the MFA’s Lane Collection, a treasure trove of 20th-century American art. Particularly striking is Harris’s visible kinship with New Yorker Arthur Dove (1880-1946), who, like Harris, started as a commercial illustrator and then turned to painting that was responsive to nature. Dove went further into abstraction than Harris but nature is always a palpable presence in his paintings, which seem like jazz improvisations in response to the play of light and sea in Long Island Sound.

The MFA’s Taylor L. Poulin curated the second gallery of American modernists, which features Italian-American immigrant Joseph Stella’s magnificent “Old Brooklyn Bridge” (1941), a rhapsody of curves and lines celebrating the new world’s verve. Nearby, are explorations of form in industry by Charles Sheeler, who, like his peers, crossed the line between abstraction and illustration.

Juxtaposed with works by the Americans are two by Harris. In his oil painting “Ice House, Coldwell, Lake Superior” (1923), the contours of the shacks and dock blaze in the fire of an unseen sunset. A pen-and-ink drawing “Miners’ houses, Glacier Bay” (1926) captures a cascade of row houses marching in raked light. In counterpoint to this geometric order, in one window, a curtain furls in the breeze.

The main gallery of Harris landscapes groups the paintings by the three regions of Canada that inspired them: Lake Superior, the Arctic, and the Rocky Mountains. In 1921, at age 36, Harris made the first of several trips to the north shore of Lake Superior. Three years later, he took his first sketching trip to the Canadian Rockies and returned for five consecutive summers. In 1930, Harris traveled through the Arctic for two months on a government supply ship.

Compelling even when small (12” by 15”) in size, the first set of images shows scenes from the northernmost reaches of Lake Superior. Among them is the intense “Pic Island” (1924), an uncrowded haiku of textures and shapes. Crossing its eggplant colored terrain are horizontal bands of gold and blue sky that magnify a sense of space. Another miniature, “The Old Stump, Lake Superior” (1926), a closeup of a lone tree stripped by wildfire, is infused by radiant light that evokes a sacred scene in an Italian Renaissance painting.

Harris spoke of striving for paintings that “stood for all mountains.” In a series of journeys to the Canadian north, he made hundreds of pencil drawings that he later refined into paintings — a process that Cynthia Burlingham of the Hammer Museum describes in a fine essay in the show’s catalog.

Harris records and heightens the surreal extremes he observes in nature in such paintings as “North Shore Baffin Island” (1930), with its sharply tipped peaks; and in “Mt. Thule, Bylot Island” (1930), which shows the mirror-like reflections of crags in the water.

The artist creates intimacy on a grand scale too. Displayed side-by-side, a trio of large mountain scenes seem to lean, tilt and ascend together: “Mt. Lefroy” (1930), “Mountains in Snow: Rock Mountain Painting VII” (1929), and, its peak rising like an exultant dancer springing skyward, “Mountain Forms” (1926).

The wonder of these paintings is how Harris renders a sense of timeless stillness and mystery within the continuous mutations of earth, sky and water.