Italian man of theater Dario Fo celebrated his 90th birthday on March 24, and in Boston as well as in major cities throughout the world, fans held theater festivals and academic symposia in his honor.

When Fo received the 1997 Nobel Prize in Literature, he was cited as an actor “who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden.”

Fo’s plays have been translated into more than 30 languages and millions of people have seen him perform his mime masterpiece, “Mistero Buffo (Comic Mystery),” a collection of satirical pieces based on folk tales, gospel stories and events in the daily news.

A resident of Milan, Fo speaks Italian as well as French, but his true native language is the nonverbal expressiveness of his large, nimble body, rubbery face and a voice that can roar, growl, caress or soar like a jazz saxophone. Adapting techniques of traveling street performers (“giullari”) in the rough-and-ready early days of Commedia dell’arte, Fo uses the arsenal of a standup comic to satirize those who abuse power and give voice to society’s most vulnerable people.

Fo employs no props but a microphone and often needs no translator. Performing “Mistero Buffo” at the American Repertory Theater in 1986, during his first visit to North America, he wordlessly portrayed a starving man feasting on a flea.

Tribute performances

Boston’s celebration of Fo’s birthday featured a Poet’s Theatre production of five stories from “Mistero Buffo” at Suffolk University’s Modern Theatre. Acclaimed Boston actors Remo Airaldi, Benjamin Evett, and Debra Wise performed multiple roles in the short plays, loosely based on Gospel stories. Well-staged in the intimate theater, with deft lighting by John Malinowski, the production was directed by Poets’ Theatre president and artistic director Bob Scanlan, who translated Fo’s Italian texts with Walter Valeri, who once served as Fo’s company manager.

Barefoot and wearing neutral attire, the trio began the evening with a little dance, like marionettes at the start of a commedia dell’arte routine. But defying the cardinal rule of theater to show rather than tell, the production then shifts to a short lecture by Evett on the medieval comic tradition that inspired Fo. Next, he performed a long, word-heavy solo piece, “Birth of the Giullare (Jester).” Its best moments were near the end, when Evett’s character, an oppressed peasant, serves a makeshift meal to a hungry visitor who turns out to be Jesus Christ and finds his calling — to defend the poor using his knack for humor.

Next, Remo Airnaldi performed “The Wedding at Cana,” Fo’s take on the Gospel story in which Christ turns water into wine at a wedding feast. Airnaldi has a quietness about him that draws an audience in, and he was captivating as a wedding guest who witnesses the miracle, becoming ever more joyful and inebriated as he tells his tale.

Debra Wise performed a solo, “The Resurrection of Lazarus,” Fo’s retelling of another miracle, and played Fo’s distraught Mary in the closing piece, “Mary at the Cross.”

Redemption

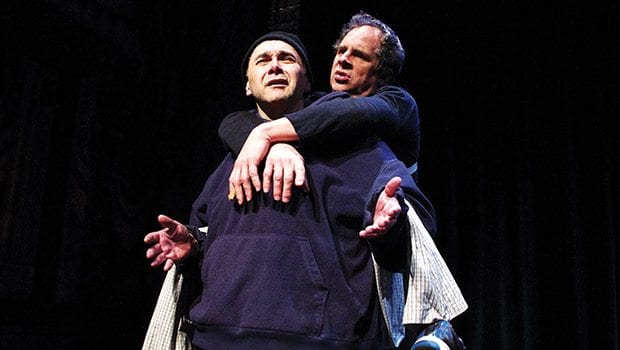

Evett and Airaldi paired up for Fo’s “The Blind Man and the Cripple,” which, like the Samuel Beckett short “Rough for Theatre I” (1979), tells the tale of two beggars who get by better as a team. But Fo’s slapstick start molts into something more. Astride Airaldi’s Blind Man, Evett’s Cripple spots Christ in the distance, healing the sick. If they are cured, the Cripple warns, they’ll “have to join the working class.” The two panic and yell, “Save me. I don’t want to be miracled.” Yet both are healed and while Evett’s beggar stomps, kicks, and frets, Airaldi expresses his character’s wonder at seeing the world.

And as they see Christ being tortured and nailed to the cross, they ask each other why people would want to harm this man who fed the hungry and healed the sick.