People in diaspora bring their culture with them as they leave their homeland. Often both the people and their culture take fresh, life-giving turns on new terrain.

Consider jazz and tap dance, two of the arts invented by African Americans as they brought rhythmic patterns and movements rooted in Africa across the Atlantic.

So, too, the tradition of Irish step dance has evolved since crossing the ocean. Like tap, it is a percussive dance tradition springing from roots in a distant homeland.

In the 1890s, after the British eased their repression of Irish culture, the newly formed Gaelic League launched small-town festivals reviving Irish language, literature and dancing. About six people competed in their first step-dancing competition. Now, church basements and community centers all over America practice its rapid, intricate foot movements and drill-like quadrille formations.

Yet new currents of step dancing have emerged over the past two decades. Colin Dunne, star of the commercial juggernaut “Riverdance,” has moved into contemporary dance, and he joined tap star Savion Glover in a Grammy-winning duet at Madison Square Garden.

New meets old

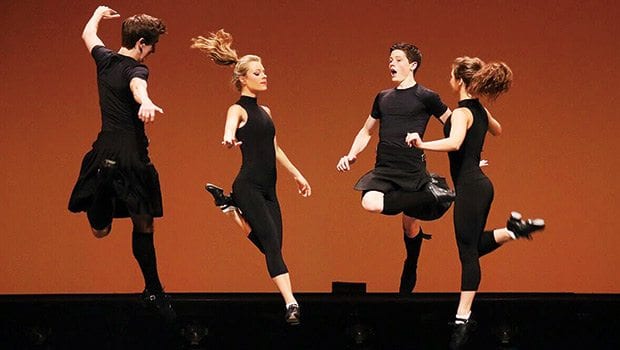

Another pioneer, Emmy award-winning choreographer Mark Howard, has injected a new-world twist into Ireland’s dance legacy. Founded 25 years ago, his renowned Chicago-based Trinity Irish Dance Company, along with its two schools in Chicago and Milwaukee, has developed a progressive style of Irish dance that blends tradition with contemporary style. While winning world championships in the old-school style, the company has collaborated with notable contemporary choreographers, including Dunne, to create works that blend the clockwork precision and fast, intricate footwork with the expressiveness of contemporary dance.

This combination was thrilling to watch last weekend as Howard’s company performed at the Emerson/Cutler Majestic Theatre, a presentation of World Music/CRASHarts.

Notable, too, was the warm tone of the dancers and musicians. Unpretentious in manner, they interacted with the audience as if visiting old friends, a tone that suits a dance tradition that was born in a rural town.

Unlike high-test productions, the two-hour show of 10 works had the atmosphere of a community event. Its congenial host was composer, singer and guitarist Brendan O’Shea, who was accompanied by fiddler Kathleen Grennan; guitarist Christopher Kurwin; Brian Holleran, playing flute, whistle and uilleann pipes, the traditional bagpipes of Ireland; and percussionist Paul Marshall, who played a drum kit as well as a bodhran, a traditional Celtic handheld drum.

Playing in a lilting acoustic musical style familiar to any devotee of an Irish pub, the musicians occasionally left their berth, a platform behind the dancers, to join a jig. Midway through the show, they sat in a circle with three dancers and took turns showing their own step-dancing prowess. Grennan was a standout.

Shadow and light

Dustin Derry’s artful staging included evocative lighting that accented the primal power of contemporary pieces.

Unafraid to be strange, the company opened its program with the stark “Communion,” by Howard and co-choreographer Sandy Silva. On an otherwise blackened stage, a triangle of light hovered over a band of dancers in dark costumes. In this fierce, minimalist work they performed sculpted, rapid movements that suggested the distilled essence of step dancing to the sounds of their stomping feet and clapping hands. They concluded by exhaling as one, like Maori completing a warriors’ dance.

In contrast to the taut power of “Communion,” a traditional work seemed almost like a parody of old-school practices, with its crisp, military precision and artifice. Following the established regimen, the dancers wore embroidered costumes with stiff shawls and rhinestone tiaras, and curly wigs resembling pale Afros. Their faces were pasted with makeup and frozen in set smiles. But plenty of people in the audience came to see this flawlessly executed spectacle. A few similarly attired small children from local schools took part, darting across the stage and performing the same steps as the adults to the delight of all.

Among the company’s collaborative works was “Curran Event,” by acclaimed contemporary choreographer Seán Curran, who as a boy in Belmont learned Irish step dancing and then became a lead dancer in the Harlem-based Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane Dance Company. The playful, vibrant piece unfolded to the wailing vocals and slow drumbeats of “Ón Taobh Tuathail Amach” by Irish folk group Kéla. The dancers wore bright plaid kilts, their hair knotted in braids, pony tails and multicolored ribbons. In Curran’s ode to joy, they leapt, clapped and slapped their bodies in bravura solos and bold formations that echoed schoolgirl games.

As the company performed works old and new, they interwove intricate visual and sound patterns. Clad in hard shoes, the dancers’ feet stomped and rippled, and in soft shoes, their toes summoned sheets of sound from the floor. With slaps, claps and sticks, the dancers turned their whole bodies into percussive instruments, injecting their own sounds into the music of the band. And in some of most riveting moments, they moved in silence.