Nick Offerman brings Ignatius J. Reilly to life in ‘ A Confederacy of Dunces’

In the sensational opening scene of the Huntington Theatre Company production “A Confederacy of Dunces,” an adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s novel of the same name, actor Nick Offerman (Ron Swanson in NBC’s “Parks and Recreation”) undergoes a metamorphosis.

Offerman steps on stage in long johns. A small posse of cast members surrounds him and packs him into a fat suit. Before our eyes, he becomes the novel’s elephantine antihero, Ignatius J. Reilly, from his green hunting cap and plaid flannel shirt to his vast trousers and worn desert boots.

As Ignatius stands before us, the cast of characters with whom he will interact crosses the stage in a slow procession.

The frank acknowledgement of theatrical illusion sets the stage for another metamorphosis, the transformation of Toole’s teeming novel into a two-hour play.

On stage at the Boston University Theatre through December 20, the world premier production aims to distill rather than recreate the novel. The production uses no props and hardly any sets — just a few sliding panels to conjure swiftly changing settings. Its spare staging pays tribute to its source, allowing viewers, like readers, to use their imagination to fill in the details.

Adapted by Jeffrey Hatcher, whose script incorporates plenty of dialogue from the novel, and directed by David Esbjornson, the production focuses on the characters and atmosphere conjured by Toole’s novel, set in the author’s hometown, New Orleans.

The production evokes the carnival-like world of the novel, which holds up a funhouse mirror to life, starting with the hugely magnified figure of Ignatius.

The streamlined staging integrates scenic design by Ricardo Hernandez, pastel-toned costumes by Michael Krass, warm lighting by Scott Zielinski, sound design by Charles Coes and Mark Bennett, and projections by Sven Ortel that show atmospheric New Orleans landmarks such as the Café du Monde as well as images that stand in for props.

The sound of a beer mug scraping a tabletop comes from a sound projection, not an actual mug. When Ignatius whips workers into staging an uprising, the actors hold up their arms as if brandishing hoes and shovels. Projected on a backdrop behind the ensemble, silhouettes of these objects appear to fill their hands.

The show’s tasty music includes compositions by Bennett and wafts of such classics as Fats Domino’s “Walking to New Orleans” and “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Performing onstage are trombonist David L. Harris and pianist Wayne Barker, music director, who also plays a bartender.

Laid-back radical

Ignatius J. Reilly is a scholarly slob who lives with his mother in 1960s New Orleans. When not watching movies and eating, he writes manifestos and hatches revolutionary schemes to better the world. But when his mother backs her car into a building, he has to get a job to help her pay the damages. As he takes to the streets, Ignatius encounters a host of oddballs, fellow denizens of the Crescent City. Outrageous in appearance and behavior, Ignatius creates a trail of chaos. Yet he and the characters he encounters end up better off.

Toole was a popular college professor, and he infused his novel with learning as well as the oddities and charm of his hometown. He drew its title from an essay by 18th century satirist Jonathan Swift, who wrote, “When a true genius appears, you can know him by this sign: that all the dunces are in a confederacy against him.”

Ignatius quotes from “The Consolation of Philosophy,” a sixth century meditation on good and evil and the fickle turns of fortune. Embracing the stoic worldview of its author Boethius, Ignatius declares that “it is the fate of man to be at the mercy of a blind goddess named Fortuna upon whose wheel he is crushed endlessly.”

Yet in both the novel and play, humor and imagination leaven a cruel world.

Toole gave Ignatius a kinder fate than his own. A troubled soul whose inability to find a publisher for his novel added to his distress, Toole committed suicide in 1969, at age 32. A decade later, Southern novelist Walker Percy read the manuscript at the behest of Toole’s mother, pronounced it a masterpiece, and got it into print. In 1981, a year after its publication, the novel won the Pulitzer Prize and since then has sold more than 3.5 million copies in 24 languages.

The superb 15-member ensemble, including Offerman and the two musicians, play a total of 21 characters. They keep the humanity of their roles intact and at the same time, pull off slapstick scenes that include tumbles, toppling bodies and a skirmish with a strip tease dancer’s pet cockatoo.

Good chemistry

But despite its fine cast and artful, spare staging, the production wears cartoon-thin in a few scenes, when an overload of characters and activity clutters the stage. The production is at its best when the magnetic Offerman interacts with one character at a time. In such scenes, Offerman and his fellow actors conjure an on-stage chemistry that matches the novel in pleasure.

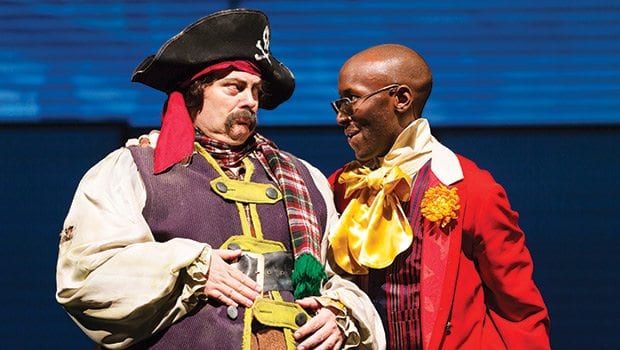

Arnie Burton is a marvel in his two roles: the hapless, benign factory manager Mr. Gonzales, scrambling to keep chaos at bay after hiring Ignatius; and the gay dandy Dorian Greene, who matches wits and attitude in a faceoff with Ignatius, who is attired in a billowing pirate outfit, the better to merchandise hot dogs.

Paul Melendy is a natural as the benevolent and beleaguered Patrolman Mancuso, whose array of undercover disguises is worthy of a Mardi Gras parade — from a nun’s habit to the dour garb of an Amish farmer. Philip James Brannon is outstanding as Burma Jones, a jive-spouting black man determined to outwit his oppressive boss and get a job that pays a living wage.

In a bravura turn, Anita Gillette endows Irene Reilly, the mother of Ignatius, with the daffy high spirits to attract a suitor and the anguish to face the toll that her son has taken on her life.

Stephanie DiMaggio excels as both Lana Lee, the mean proprietor of a barroom, and Myrna Minkoff, the girlfriend of Ignatius who has decamped to New York City. Both Myrna and Ignatius aspire to be revolutionaries. But after their various campaigns to save the world fail, they finally find a bit of success in saving one another.

Improbable but fun to watch, deliverance arrives through a collision of coincidences as dizzy as the plot of a Marx Brothers comedy.

In the concluding scene of both the book and the play, Ignatius shows a hint of something new: a grace note of gratitude. Contented at last, he brings the tip of Myrna’s long brown braid to his lips and breathes it in as if he were inhaling a fine cigar.