Bus Rapid Transit studied anew for Hub

Dudley to Mattapan, Harvard seen as feasible routes

The addition of “Gold Standard” Bus Rapid Transit lanes could cut travel time by nearly half between Dudley and Haymarket or Harvard, and by more than one-third between Dudley and Mattapan, according to a report on BRT by the Barr Foundation, a Boston-based private foundation that focuses on education, climate, and arts and culture.

The Barr Foundation convened the Greater Boston BRT Study Group in 2013 to look into how and where new dedicated BRT lanes might improve Boston transportation. The group’s report, “Better Rapid Transit for Greater Boston,” released in June, suggests that BRT — if implemented at its highest standard — could be a cost-effective option to improve access and efficiency in several of the city’s transit corridors.

“Transit is the life blood of the city,” said Jackie Douglas, executive director of LivableStreets Alliance and a member of the BRT Study Group. “This was an opportunity to deep-dive into one option for transportation across the region.”

Partnering with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), the Study Group, made up of community leaders and academic and transit experts from across Boston, examined 18 possible routes and then narrowed the list to five priority corridors: Dudley to Downtown, Dudley to Mattapan, Readville to Forest Hills, Harvard to Dudley, and Sullivan Square to Longwood Area.

The corridors were identified as meeting key criteria: reduce existing congestion on the T; serve underserved communities or groups; meet additional demand by providing a more direct travel option; and address the need for planned future development.

Reducing travel time to 30 minutes between Dudley and Harvard, the report says, would improve connectivity between academic and life science clusters and reduce traffic congestion around Red Sox games; with a Dudley-to-Mattapan route, BRT would serve “tremendous demand and potential” along Blue Hill Avenue.

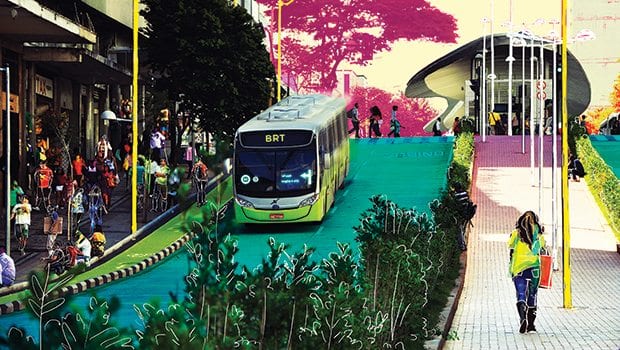

Mary Skelton Roberts, Barr’s senior program officer for climate, has observed successful BRT implementations in Mexico and Colombia, systems she described as are far above what people might picture when imagining improved bus service. She emphasized that the Boston BRT report focuses on the Gold Standard — true BRT characterized by enclosed stations, pre-paid fare collection, and physically-separated bus-only lanes.

Author: Artwork by Ad Hoc IndustriesAdvocates say commuters would shave minutes off the Dudley Square to Downtown Crossing ride on the Silver Line were it a genuine bus rapid transit line.

Few U.S. cities have true BRT, and Boston is no exception.

“The Silver Line is not BRT,” Skelton Roberts emphasized.

She said the Silver Line, occupying the path of the old elevated Orange Line and seen by many Bostonians as a disappointing substitute for light rail, falls short even of “Bronze-level” BRT. In its above-ground sections, fares are still collected one-by-one as passengers board, and Silver Line buses are slowed as their lanes have to be shared with bicycles and with right-turning or double-parked vehicles.

The Barr Foundation’s approach was to examine BRT’s technical feasibility for Boston first, Skelton Roberts said, and with that knowledge in hand, gather community response.

“It makes no sense to engage any community in a discussion if you can’t even build it,” she said.

Malia Lazu, executive director of Future Boston, was in the Study Group. Since the report release, she has been posting frequently on Twitter about BRT, urging followers to weigh in on questions like “How would your life change if you could connect quickly to any neighborhood in the city via #MBTA?” and providing links to the BRT report.

Lazu said neither she nor her organization are pushing BRT, but instead are working to ramp up the discussion.

“We don’t know if the community is going to like this, but we think it’s worth having a conversation. Our tweets are asking questions, asking what people think,” she said.

Besides the Silver Line’s quasi-BRT promise, other BRT proposals have been floated for Boston. In recent years, BRT was proposed for Melnea Cass Boulevard, but that plan has been put on hold in response to community concerns about widening the street and skepticism about the usefulness of a short BRT route.

In 2009, the “28X” proposal for Blue Hill Avenue, to be funded with American Recovery and Reinvestment Act dollars, was scuttled in the face of community reluctance, some of it general and some particularly around the difficulty of siting BRT lanes on the narrower Warren Street in Roxbury.

“With 28X,” Skelton Roberts said, “I don’t think there was enough time. There was some federal funding, so there was urgency. It looked suspicious. It seemed very solution-oriented, without input from the community.”

Missed opportunity?

State Rep. Russell Holmes, whose was elected to his Mattapan district after the 28X rejection, still regrets that his community did not take advantage of the federal funds. He is pleased to see that the new report validates his office’s findings on high rider demand along Blue Hill Avenue.

“I look forward to the discussions beginning anew. I think BRT would serve my district, my folks,” Holmes said.

“There will be nothing smooth about this process, because of the history of 28X,” Holmes added. [But] we need people to be able to get to the center city and to jobs faster.”

Holmes was not part of the BRT Study Group, but will be among the community members and leaders heading to Mexico City with the Barr Foundation in November to look at BRT there. He said he did play a role in advising the Barr Foundation on engaging the community properly.

“I said, get into the neighborhoods, make sure you come at this by addressing what’s important to the neighborhood,” Holmes said. “You’re going to need the will of the people to do this. And you have to show people what real BRT looks like.”

Some events this month in Roxbury and Mattapan are intended to show what BRT might look like and spark community input.

On the Web

More information:

See the BRT report: www.bostonbrt.org

Dudley Square workshop info: http://tinyurl.com/brttools

MassDOT 28X plan (2009): http://bit.ly/ 1Lw0brA

Future Boston on Twitter: @futureboston

Barr Foundation: www.barrfoundation.org

In Mattapan Square on Oct. 22 or 23, Future Boston will facilitate an “information-collecting experience,” Lazu said. The public event will include visual images of Gold Standard BRT lines and an artist-led “civic hack” to investigate transportation solutions. (Further event details will be posted at www.futureboston.com.)

In Dudley Square this week, MIT’s Media Lab and Urban Studies and Planning departments are partnering with Nuestra Comunidad on a series of BRT modeling workshops Oct. 8–10 at the Roxbury Innovation Center, followed by a several-day public exhibit. To sign up for a workshop, see http://tinyurl.com/brttools or call 781-606-0278.

Dr. Ryan Chin, a Media Lab research scientist, said his group has combined a Lego-based physical model with electronic data, enabling visitors to see, play with and compare what transportation looks like with standard bus systems vs. varied levels of BRT service. His group will be studying how residents engage with this new type of modeling.

“Historically, community development has been from the top down — a ‘design and defend’ process,” Chin said. “We don’t want that. We want a co-creative process based on open data. The tools we have should be able to provide high level of detail on the tradeoffs [of different transportation options].”

Tradeoffs to consider with BRT include a reduction in the number of bus stops but a faster trip once on the bus, and loss of a traffic or parking lane but a possible benefit of having a lane freed from the in-and-out movement of buses.

State Rep. Byron Rushing was not in the Study Group but has watched local transportation politics for many years. He expressed uncertainty on the report’s rosy picture.

“They are suggesting that it is possible to do real BRT in Boston. I’m not sure if that’s true,” said Rushing. “There is no solution if it doesn’t spend as much time on the politics as the technology.”

Rushing echoed past concerns about how BRT could be implemented on narrow but significant transportation routes, such as Warren Street around Dudley Square.

“If you want faster public transit on Blue Hill Avenue,” he said, “you have to have a tunnel under Roxbury. Is this feasible? Yes. But affordable? Not right now.”

Bottlenecks

The Study Group report acknowledges that Warren Street poses a thorny problem, but suggests that it is one worth pondering.

“Alternatives to the narrow section of Warren Street … are limited,” the report says. “With the very high existing demand … it would be a mistake to overlook the benefits BRT could hold for this important corridor. But any proposed BRT corridor must be driven by the communities’ demand and vision for the neighborhoods involved.”

The BRT Study Group members were Eric Bourassa, Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC); Rick Dimino, A Better City; Jackie Douglas, LivableStreets Alliance; Ben Forman, MassINC; Chris Hart, Institute for Human Centered Design; Melissa Jones, Boston LISC; Malia Lazu, Future Boston; David Lee, Stull & Lee Inc., Architecture and Planning; Bill Lyons, Urban Land Institute of Boston; Tom Nally, A Better City; David Price, Nuestra Comunidad Development Corporation; Jessica Robertson, MAPC; Paul Schimek, TranSystems; Darnell Williams, Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts; and Chris Zegras, MIT.