‘Gang’ label poorly understood, brings serious consequences for Hub teens

More police stops for those labeled under secretive system

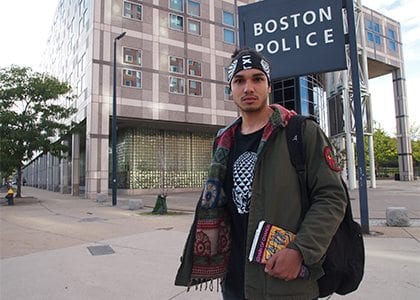

Alex Ponte-Capellan, now 24, was a student at Brighton High School when a police officer informed him he was on their “gang list.” He had never been in a gang, he told the Banner.

Like untold numbers of teenagers and young adults in Boston, Ponte-Capellan’s entry into the police database triggered a higher level of police scrutiny, including frequent stops and illegal searches.

“They [the officers] had a file on me and all of my friends, picture, and basic information about all of us,” Ponte-Capellan said. “They just told me I was on whatever list of theirs. And that they were watching me, basically.”

Ponte-Capellan said a fight most likely triggered the increased scrutiny. The altercation was sparked when he and his friends confronted a larger group of kids about an iPod they had stolen from one of his friends. The kids turned violent, Ponte-Capellan said, and in the ensuing fight he was stabbed. When the police arrived, all of them fled.

He said the group of kids he and his friends had fought were from the same neighborhood, which might have seemed like a gang.

“I know that different neighborhoods have beef with other neighborhoods. It wasn’t a formal gang, it was just a neighborhood.”

Stops and searches

The day after the fight, police were waiting for Ponte-Capellan at school outside his homeroom. They searched his person and backpack, and broke the lock off his locker to search it as well. The officers spoke with the school disciplinary staff and his parents. They visited his home to speak to his parents a couple times during the next few months.

Ponte-Capellan, then 16, had gone to meet friends in Roxbury a few days after the fight, when officers called him over to their cruiser and started talking to him about their gang list. They showed him the file and told him his friends said he was the leader of their “gang.”

His friends, said Ponte-Capellan, denied this.

Before police pegged him as a gang member, Ponte-Capellan said officers would stop and pat him down him about three times a week. After the fight — and subsequent positioning on the gang list — it got worse.

“Every time I came back to downtown after that, they were all over me.”

Criminal justice reform activists say that when teens like Ponte-Capellan are labeled gang members — rightly or wrongly — they often are subjected to higher levels of police scrutiny, including surveillance and frequent stops and searches. And the cops who target the teens, members of the department’s Youth Violence Strike Force — commonly referred to as the gang unit — have a long reputation for aggressive behavior and disregard for teens’ Fourth Amendment protections against illegal search and seizure.

Ponte-Capellan said the police frequently searched his pockets without his permission, despite not having probable cause to arrest him.

The increased police harassment took a toll.

“It had a psychological impact on me,” Ponte-Capellan said. “I was a good kid. I went to school. When the police came down on me, it made me think differently of myself.”

Ponte-Capellan eventually dropped out of high school and joined the Almighty Latin King and Queen Nation — better known as the Latin Kings. After two years, he left and returned to high school, graduating from the Notre Dame Education Center. He now works with the criminal justice reform group, Youth Against Mass Incarceration.

The list

For years, police have kept lists of young men they say are either gang members or gang-affiliated. Few outside the police department understand the gang list’s workings, how gang affiliation is determined, what constitutes a gang and how the police’s gang database is managed.

Yet these lists impact the lives of those on it, as being regarded as part of a gang can increase the frequency with which police engage with an individual.

In a report released last year, researchers found that of the 204,000 field interrogations Boston Police made between 2007 and 2010, 63 percent were interrogations of people police identified as black, 22 percent were identified as white and 12 percent were identified as Latino. Blacks make up 23 percent of the city’s population. Non-Hispanic whites make up 45 percent.

Police cited gang involvement as a major factor in the disproportionate number of blacks and Latinos who were stopped, patted down, questioned or simply observed in their Field Intelligence Observation database.

The BPD did not respond by the Banner’s press deadline to requests for information about their definition of gang involvement and about policies governing their gang lists and databases.

Activists familiar with the police department’s practices say their use of the list, and the secrecy they maintain around it, pose important questions.

Makis Antzoulatos, a Boston attorney and member of the National Lawyers Guild, believes Boston’s Youth Violence Strike Force continues to operate under the gang definition it created in 1993. The definition is broad: a formal or informal group of 3 or more people with current or past criminal activity and either claimed territory or some form of identifier, such as name or colors.

Membership indicators that may justify an FIO database entry range from self-admission to being seen in the company of gang members on at least two occasions.

Individuals may also enter the database as “gang associates”, a term provided for those the police consider closely connected to a gang, but who did not fit the specified criteria.

“What we have is an unchecked situation,” says Carlton Williams, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts. “We do know that police are profiling and that race is one of the indicators of who they’re stopping. We can’t monitor how or why they’re putting people of color on their gang list. It raises concerns. How do we know that people are being treated fairly? We don’t.”

Serious consequences

In addition to stops and searches, people listed as gang affiliates or members also are subjected to worse treatment in the criminal justice system, beginning with the bail process.

“It can be used by a District Attorney to advocate for increased bail,” said Antzoulatos. “People who are freed on bail are more likely to have a positive outcome in their cases.”

Antzoulatos said police also use alleged gang affiliation or membership to justify searches that otherwise would be illegal.

Perhaps most frustrating, Anzoulatos said, is the secrecy around the list. Once when he requested a record from the police database showing his client’s alleged gang membership, he was given a single page with little information, other than his client’s name and photograph.

“There was no information in the document about how he got on the list, who said he was a gang member or anything,” Anzoulatos said. “They don’t tell us how you got on the list and there’s no information about how to get off the list.”

Gang outreach

In addition to increased police scrutiny, people on the police department’s gang list are sometimes targeted for services.

Partnerships Advancing Communities Together, launched in 2010, lists 200-300 of an estimated 3,500 “gang affiliates” in Boston, according to a report by the United States Attorney’s Office. PACT aims to connect those involved, or at risk of involvement, in gang or firearm violence with social and financial support, such as jobs, health care, education and counseling in order to turn them from violence.

Stephanie Berkowitz, director of external relations for the Center for Teen Empowerment, helps connect job opportunities with some youth the BPD regards as at risk of gang-involvement.

Both those likely to perpetrate or be victims of violence are listed, said Berkowitz. She said that a strong effort is made to protect the privacy of those on the list.

“It’s actually very secretive,” Berkowitz said. She said that currently the Boston list consists solely of young men, but she did not know other details, such as what factors put someone on this list or under what conditions they are removed.

Avoiding conflict

Ponte-Capellan said he was offered no such assistance. He doesn’t know whether he’s still on the gang list, but he has only been stopped once in the last year.

His lack of contact with the police could well be the result of changed habits. These days, he says he avoids hanging out with large groups of people, especially if he does not know everyone in the group out of fear of how the police might treat him.

“I’m just afraid if the police do come, they’re going to associate me with everyone there, and I don’t want to deal with that.”

Yawu Miller contributed to this story.